Executive Board’s assessment

An efficient and secure payment system is essential for economic and financial stability. If payments cannot be paid, economic activity comes to a halt. Being able to pay for goods and services is important for individuals to fully participate in society.

Norges Bank assesses the financial infrastructure in Norway as secure and efficient, operations are stable and payments can be made swiftly, at low cost.

Rapid technological advances, the complexity of the payment system and the difficult geopolitical situation have made payment system security and contingency arrangements both more important and more demanding than they used to be. Security and contingency arrangements require prioritisation at all levels of the payment system: individual entities, the financial sector, and across sectors and borders. As regards security and contingency preparedness, Norges Bank collaborates with other public bodies, the business sector and authorities in other countries. For example, the Bank is involved in testing the cyber resilience of critical functions and designing a framework for assessing ICT-related risk. In November 2023, the Ministry of Finance laid down the mandate for a working group to assess whether there is a need to strengthen contingency arrangements in the payment system. The working group is led by Norges Bank and will assess in particular the need for independent contingency arrangements.

Norges Bank’s settlement system comprises the core of the payment system. Today’s system is efficient, stable and secure. Norges Bank is currently researching the next generation settlement system to also ensure efficient, stable and secure operations in the future. Two alternative models are being examined: a separate dedicated solution for Norges Bank (as in the current settlement system) and participation in the Eurosystem’s collaboration on a common platform for payment settlement, TARGET Services. The settlement system must satisfy strict security, continuity and contingency requirements. The alternatives for the next generation settlement system are being assessed according to Norges Bank’s own requirements and needs, international principles for financial market infrastructures (FMIs) drawn up by the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), as well as requirements in the Security Act. The settlement system must also provide a basis that enables both private and public market participants to develop and offer modern payment services.

A well-functioning system for real-time payments is a key component of an efficient payment system. The current real-time payment solution in Norway, NICS Real, is operated by Bits. Norges Bank is studying how the real-time payment system should be developed ahead. Since 2022, Norges Bank has been in dialogue with the European Central Bank (ECB) regarding participation in TARGET Instant Payment Settlement (TIPS). This work is in its final phase and will lead to a decision basis for potential participation. In the event of a transition to TIPS, banks in Norway will have access to the same real-time payment infrastructure as banks in the other Nordic countries.

Norway is one of the countries with the lowest cash usage, both with regard to the amount of cash in circulation as a share of total means of payment and cash payments as a share of total payments. Cash does, however, serve an important contingency function should electronic payment systems fail. For cash to be able to function in a contingency, it must be available and easy to use in normal times. In addition, cash is especially important for those who do not have the skills or opportunity to use digital solutions.

Maintaining the cash infrastructure necessary for cash to be sufficiently available and easy to use entails costs. The costs must be weighed against the key functions of cash.

Norges Bank is responsible for supplying banks with cash and meeting societal demand, both in normal times and in contingency and crisis situations. In the light of the intensified risks and expanded threat landscape, Norges Bank has strengthened contingency arrangements for delivering cash to banks in crisis situations. In order for cash to reach the public, banks must also have adequate contingency arrangements in place.

In June, the Storting (Norwegian parliament) passed a legislative amendment clarifying the right to pay cash. According to the amendment, consumers have the right to pay with cash at points of sale where businesses regularly sell goods or services, assuming goods or services can be paid for at the point of sale. Norges Bank is of the opinion that the amendment is important for ensuring that cash can continue to fulfil its functions.

The Norwegian krone must be an attractive and secure means of payment in the future too. Norges Bank is assessing whether a Norwegian central bank digital currency (CBDC) is a suitable instrument for ensuring access to a means of settlement trusted by all, also in new payment arenas, and for promoting responsible innovation and improving payment contingency arrangements. In addition to retail CBDCs generally accessible to the public, wholesale CBDCs are also being examined. These are central bank reserves in tokenised form using distributed ledger technology (DLT) or other programmable platforms. Such CBDCs can be a secure means of settlement in transfers and the trading of tokenised money, securities and other assets. Tokenisation and settlement solutions in central bank money have received growing attention internationally.

In 2023, Norges Bank completed the fourth phase of its research on CBDCs. This phase consisted of experimental testing of technical solutions, analyses of scenarios for the payment system, the evaluation of consequences for liquidity management and monetary policy and a review of the legislative changes necessary for an introduction of CBDC. The fifth phase will conclude in 2025. The research project will provide a decision basis for, and an assessment of, whether Norges Bank should work to introduce a CBDC, and if so, the type of design. As global work on CBDCs is still in a phase marked by experimentation and impact assessments, more knowledge, collaboration and standardisation is needed. The ECB is likely the central bank in advanced economies that has made the most progress in retail CBDCs. In autumn 2023, the Executive Board of the ECB decided to continue its work on the digital euro in a preparation phase, which was planned to continue until 1 November 2025.

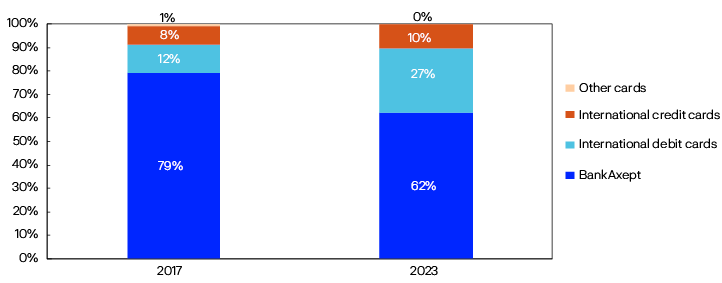

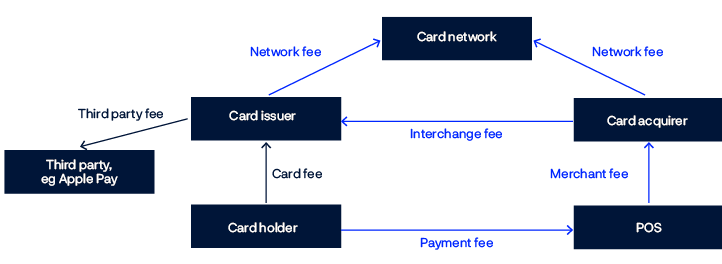

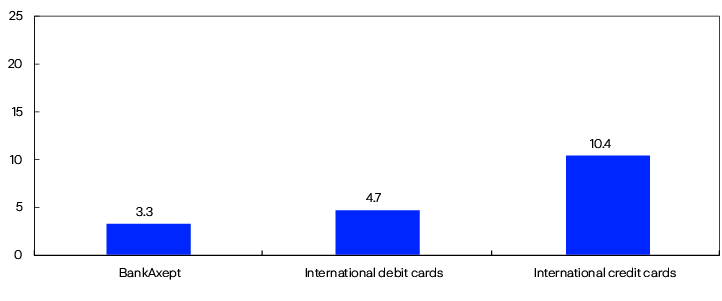

Costs in the Norwegian payment system are low by international standards. When the party selecting a payment service faces fees that reflect the marginal cost of providing payment services, they have an incentive to pay cost-efficiently. Rules in the EU/EEA prohibit such fees for payments with the most common payment cards. The merchant therefore bears most of the payment costs. When payment is made with a co-badged card, using the national debit card, BankAxept, and an international card, the merchant can preselect in the card terminal which card network is to be used (BankAxept, the national debit card or an international card). This makes an important contribution to the system’s cost efficiency. Under the regulations, however, the payer must have the opportunity to override the merchant’s selection.The growing use of mobile payments with international cards at physical points of sale is pushing up payment costs. It is important that the payment card with the lowest costs, BankAxept, is also made available for mobile payments. Merchants should also be able to preselect the card network to be used for mobile payments with co-badged cards.

There have been a number of cases of billing fees materially exceeding the cost of issuing a bill. This entails a transfer of income from the recipient to the issuer and a disproportionately low use of payment services that are priced too high. Some billers have recently reduced their fees. Letters and statements from the Norwegian Consumer Authority may mean that other billers also reduce their fees. If not, the authorities may consider introducing regulations that put an explicit cap on billing fees.

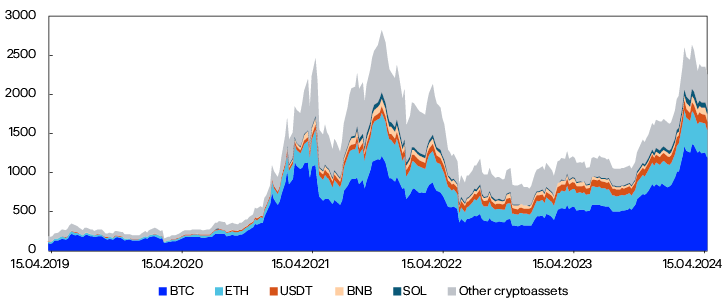

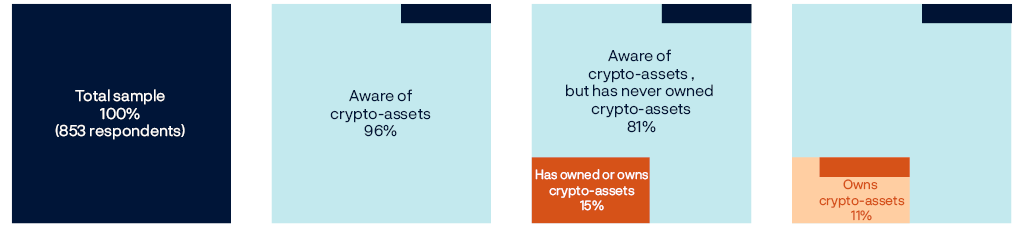

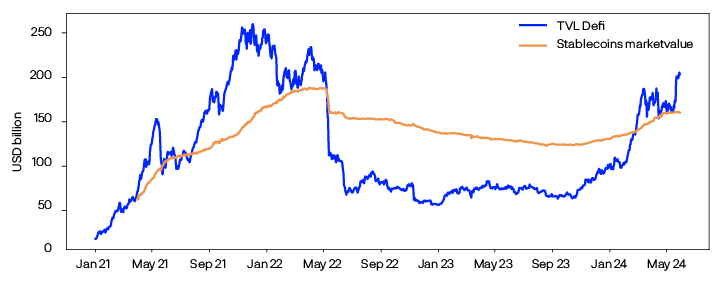

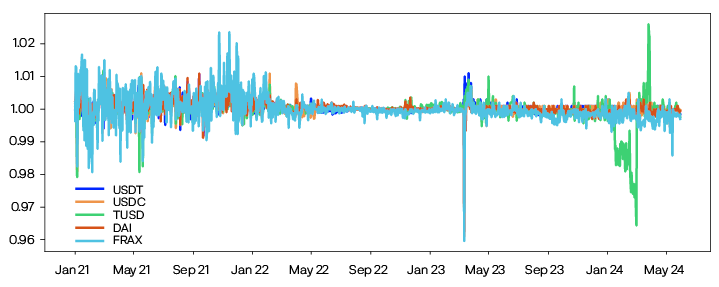

The value of crypto-assets has been highly volatile and the cypto-asset market has been marked by speculation. A survey conducted by Norges Bank in 2024 shows that 11% of the Norwegian population are crypto-asset holders. The purchase and use of crypto-assets is associated with risk, partly as a result of value fluctuations. New products and services can increase interconnectedness between crypto-assets and traditional financial assets and thus systemic risk associated with crypto-assets. Further regulation may be necessary to mitigate systemic risk from stablecoins as some of these assets may fall outside the scope of the new EU/EEA MiCA regulation.

The Executive Board

14 May 2024

Norges Bank’s responsibilities

Norges Bank is tasked with promoting financial stability and an efficient and secure payment system.1 The Bank’s tasks in this regard comprise:

- Overseeing the payment system and other financial infrastructure and contributing to contingency arrangements.

- Supervising interbank systems.

- Providing for a stable and efficient system for payment, clearing and settlement between entities with accounts at Norges Bank.

- Issuing banknotes and coins and ensuring their efficient functioning as a means of payment.

As operator, Norges Bank ensures efficient and secure operating platforms and sets the terms for the services the Bank provides. As supervisory authority, Norges Bank sets requirements for licensed interbank systems. Through its oversight work, Norges Bank urges participants to make changes that contribute to maintaining an efficient and secure financial infrastructure. An efficient payment system carries out payment transactions swiftly, at low cost and tailored to users’ needs.

Norges Bank’s use of instruments in different areas will vary over time and be adapted to developments in the payment system and the financial infrastructure. Norges Bank is tasked with giving advice to the Ministry of Finance when measures should be implemented by bodies other than the Bank in order to meet the objectives of the central bank.

Financial infrastructure

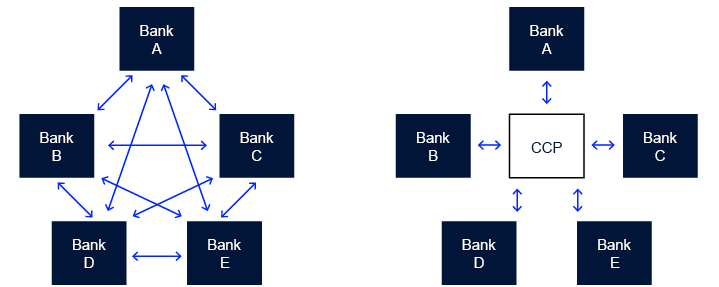

The financial infrastructure can be defined as a network of systems, called financial market infrastructures (FMIs), that enable users to perform financial transactions. The infrastructure must ensure that cash payments and transactions in financial instruments are recorded, cleared and settled and that information on the size of holdings is stored.

Virtually all financial transactions require the use of the financial infrastructure. Thus, the financial infrastructure plays a key role in ensuring financial stability. The costs to society of a disruption in the financial infrastructure may be considerably higher than the FMI’s private costs. The financial infrastructure is therefore subject to regulation, supervision and oversight by the authorities.

The financial infrastructure consists of the payment system, the securities settlement system, central securities depositories (CSDs), central counterparties (CCPs) and trade repositories.

Norges Bank’s supervision and oversight work

Norges Bank is the licensing and supervisory authority for the part of the payment system called interbank systems (Table 1). These are systems for clearing and settling transactions between credit institutions. If a licensed interbank system is not configured in accordance with the Payment Systems Act or the licence terms, Norges Bank will require that the interbank system owner rectify the situation. The purpose is to ensure that interbank systems are organised in a manner that promotes financial stability. Norges Bank may grant exemptions from the licensing requirement for interbank systems considered to have no significant effect on financial stability.

Oversight entails monitoring FMIs, following developments and acting as a driving force for improvements. This work enables Norges Bank to recommend changes that can make the payment system and other FMIs more secure and efficient. Norges Bank oversees the payment system as a whole and key FMIs are subject to a permanent and regular oversight arrangement (Table 1).

Norges Bank assesses the FMIs that are subject to supervision and oversight in accordance with principles drawn up by the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO).2 The CPMI is a committee comprising representatives of central banks, and IOSCO is the international organisation of securities market regulators. The objective of the principles is to ensure a robust financial infrastructure that promotes financial stability.

A number of the FMIs that Norges Bank supervises or oversees are also followed up by other government bodies. The oversight of international FMIs that are important for the financial sector in Norway takes place through participation in international collaborative arrangements.

Finanstilsynet (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway) supervises systems for payment services. These are retail systems, which the public has access to, such as cash, card schemes and payment applications. The Central Bank Act from 2019 clarifies that Norges Bank’s oversight covers the payment system as a whole, including retail systems that Finanstilsynet supervises. The preparatory works for the Central Bank Act state that in its oversight of the payment system, Norges Bank should be able to make appropriate use of Finanstilsynet’s assessments of retail systems, especially with regard to their security.

Definitions in the Payment Systems Act

Payment systems are interbank systems and systems for payment services.

Interbank systems are systems for the transfer of funds between banks with common rules for clearing and settlement.

Systems for payment services are systems for the transfer of funds between customer accounts in banks or other undertakings authorised to provide payment services.

Securities settlement systems are systems based on common rules for clearing, settlement or transfer of financial instruments.

A detailed description of the FMIs supervised or overseen by Norges Bank is provided in Norway’s financial system 2023.3

Table 1 FMIs subject to supervision or oversight by Norges Bank

|

FMI |

Instrument |

Operator |

Norges Bank’s role |

Other responsible authorities |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Interbank systems |

Norges Bank’s settlement system (NBO) |

Cash |

Norges Bank |

Supervision (Norges Bank’s Supervisory Council) and oversight |

Supervision: Norwegian National Security Authority |

|

Norwegian Interbank Clearing System (NICS) |

Cash |

Bits |

Licensing and supervision |

Supervision: Norwegian National Security Authority |

|

|

DNB’s settlement bank system |

Cash |

DNB Bank |

Licensing and supervision |

Licensing and supervision of the bank as a whole: Finanstilsynet and Ministry of Finance |

|

|

SpareBank 1 settlement bank system |

Cash |

SpareBank 1 SMN |

Oversight |

Licensing and supervision of the bank as a whole: Finanstilsynet and Ministry of Finance |

|

|

CLS |

Cash |

CLS Bank International |

Oversight in collaboration with other authorities |

Licensing: Federal Reserve Board Supervision: Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Oversight: Central banks whose currencies are traded at CLS (including Norges Bank) |

|

|

Securities settlement systems |

Euronext Securities Oslo’s central securities depository business |

Securities and cash |

Euronext Securities Oslo and Norges Bank |

Oversight |

Licensing and supervision of Euronext Securities Oslo: Finanstilsynet |

|

LCH’s central counterparty system |

Financial instruments |

LCH |

Oversight in collaboration with other authorities |

Supervision: Bank of England Oversight: EMIR College and Global College (including Norges Bank) |

|

|

Cboe Clear Europe’s central counterparty system |

Financial instruments |

Cboe Clear Europe |

Oversight in collaboration with other authorities |

Supervision: Dutch central bank Oversight: EMIR College (including Norges Bank) |

|

1 Section 1-2 of the Central Bank Act and Section 2-1 of the Payment Systems Act.

2 Principles for financial market infrastructures. See CPMI-IOSCO (2012).v

3 Norges Bank (2023a).

1. Security and contingency arrangements

Norges Bank considers the payment system to be secure and efficient. Operations are stable and payments can be made swiftly at low cost. Geopolitical developments in recent years have made working on payment system security and contingency arrangements both more important and more demanding than before. Rapid technological advances, increased globalisation and a more complex payment system have amplified this. Individual entities that are responsible for securing their own systems will always be the first line of defence. The Bank supervises and oversees the payment system in order to promote security and efficiency. The Bank also cooperates with payment system participants and other national governing bodies on different measures for strengthening contingency arrangements.

1.1 Security and contingency arrangements have become more important and more demanding

The payment system has become more complex in recent years, with the introduction of new payment solutions, more private suppliers and longer supply chains. Digitalisation has made the payment system more dependent on underlying infrastructure, such as electricity, telecommunications and the Internet. Concentration risk has increased owing to the consolidation of IT and data centre service providers.

The threat landscape has deteriorated in recent years. Russia’s war against Ukraine and heightened tensions in many parts of the world are having an impact on security. Cyber incidents have become more sophisticated and cyberattacks can spread rapidly owing to digital interconnectedness and interdependencies in the financial sector in Norway and across national borders.

Increasing payment system complexity and the demanding geopolitical situation have made working on security and contingency arrangements both more important and more challenging than before. Security and contingency arrangements require prioritisation at all levels: individual entities, the financial sector, and across sectors and borders.

1.2 Security in individual entities is the first line of defence

The security and contingency arrangements of individual entities are the payment system’s first line of defence. Each entity is responsible for implementing necessary measures based on their vulnerabilities and the current threat landscape.

Norwegian financial sector entities work systematically to strengthen security and contingency arrangements. Since the threat landscape has become more aggressive, more security management and contingency work is increasingly needed in each individual entity.

Outsourcing allows for effective solutions but also requires risk management and monitoring

The financial sector’s use of outsourced services has increased, and to a larger extent includes core services. Outsourcing can lead to better and more cost-effective solutions for payment services, but a higher degree of outsourcing and longer supply chains also pose challenges and give rise to vulnerabilities. Providers’ corporate structures have become more complex and often consist of a number of subcontractors that may be subject to regulation in different jurisdictions.

When services are outsourced, the principal is still responsible for the security of these services and is required to manage and control the outsourced operations. This applies across the entire supply chain and comprises all risk, including technological security and personnel security. To safeguard security, entities should therefore ensure that they can swiftly change providers and that no technical constraints are a hindrance.

To safeguard the security of critical societal infrastructure, it is essential that continuity and contingency solutions are effective and that necessary and effective measures can be implemented in a contingency situation. Critical infrastructure must therefore be subject to adequate national governance and control. Requirements for critical infrastructure to be operated in Norway or for operational contingency solutions to be established in Norway can ensure that critical systems are available in crisis situations. On the other hand, operational or contingency arrangements located outside of Norway may strengthen resilience and increase system availability in some crisis situations.

Contingency arrangements for failures in underlying infrastructure or other necessary inputs are important

To ensure that the payment system also functions during disruptions and crises, it is important that entities have contingency arrangements for failures in underlying infrastructure and other necessary input factors. This applies in particular to activities that are crucial for fundamental national functions.

Failure in underlying infrastructure such as electricity and electronic communication can affect the payment system. Moreover, supply chain disruptions, as was the case during the pandemic, may result in shortages of necessary inputs.

Even though such disruptions are outside the individual entities, it is important that the entities have supply chain contingency plans.

1.3 Norges Bank’s contribution to strengthening security and contingency arrangements in the financial sector

Norges Bank is responsible for promoting financial stability and an efficient and secure payment system. The Bank is tasked with overseeing the payment system and other financial infrastructure, and contributing to contingency arrangements. Moreover, the Bank is also the supervisory authority for interbank systems. The Bank has operational responsibility for interbank settlement and cash handling and works continuously to strengthen security and contingency arrangements for these functions. For more information, see Section 2.

Financial infrastructure security and contingency arrangements require the efforts of many entities, both public and private, and in many cases collaboration between government bodies and private entities, both nationally and internationally. Norges Bank works together with entities in the financial sector as well as other authorities in a number of areas, some of which are discussed below.

Identifying fundamental national functions

Identifying critical national payment system functions is necessary for setting proper security and contingency requirements for key entitites. The Ministry of Finance has identified three fundamental national functions in the financial system pursuant to the Security Act: 1) “the ability to finance the public sector”, 2) “securing the ability to deliver financial services” and 3) “The operations, freedom of action and decision-making ability of the Ministry of Finance”. Finanstilsynet and Norges Bank assist in identifying PSPs of vital or material importance to these fundamental national functions and have provided input to the Ministry. In recent years, based on this input, the Ministry has decided that several entities with activities related to financial infrastructure are to be subject to the Security Act’s regulation as they are assumed to either control critical national assets or engage in activities of vital importance to fundamental national functions. If these entities control critical national assets, they are thus also subject to requirements governing procurement, personnel security, information security and restrictions on ownership. Entities that control critical national assets are subject to supervision by the Norwegian National Security Authority (NSM), which helps strengthen security and contingency arrangements.

Initiatives across industries are of importance for financial infrastructure security. On 12 April 2024, the government proposed a new electronic communications act. The bill comprises requirements for security and contingency arrangements, applicable to data centre services and a duty to register, applicable to data centre operators. Norges Bank welcomes the proposal to supervise data centres and strengthen their contingency arrangements and also supported the proposal in the Bank’s consultation response.

In January 2024, the Government appointed an expert commission responsible for national control over digital infrastructure. The commission will advise on how the government can safeguard national control of critical digital communication infrastructure, such as mobile and broadband networks, as well as data centres. Norges Bank is represented in the commission, which will present its report to the Ministry of Digitalisation and Public Governance in February 2025.

Testing and exercises conducted to identify vulnerabilities and strengthen financial stability

Norges Bank conducts and participates in exercises and financial infrastructure testing internally in Norges Bank, in the financial sector, across industries and on an international level. In this area, Norges Bank collaborates with entities in the private sector as well as government bodies in Norway and abroad. The purpose is to identify and reduce vulnerabilities, thereby promoting financial stability. Some of Norges Bank’s activities are described below.

Advanced security testing conducted in accordance with the TIBER framework

Norges Bank has, in collaboration with Finanstilsynet, introduced cyber security testing in Norway, TIBER-NO, based on the TIBER-EU framework developed by the European Central Bank (ECB).

Two Norwegian tests have been conducted in accordance with TIBER-NO, and three other tests are currently being carried out. Critical functions and processes in individual entities are tested, and the entities themselves own the test results. Norges Bank is responsible for the organisation of the Norwegian TIBER team. In addition to overseeing the Norwegian tests, the team participates in cross-border TIBER testing of financial institutions with activities in Norway and head offices outside of Norway. This cross-border testing is managed by other central banks and also promotes financial stability in Norway.

Tested entities are given the opportunity to practise identifying and responding to attacks from sophisticated threat actors. Learning and improvements made from testing help to improve cyber resilience. A TIBER-NO forum has been established where experience from Norwegian and international testing is shared with financial sector entities in Norway. The Norwegian TIBER team collaborates with similar teams in other central banks to develop expertise and share experiences. The collaboration is successful at both Nordic and European levels.

Box 1.1 TIBER – Threat Intelligence-Based Ethical Red-teaming

TIBER testing emulates how real-life threat actors attack financial sector entities. The tests are comprehensive and focus on people, processes and technology. Each test is based on a Targeted Threat Intelligence Report (TTIR) that describes relevant attack scenarios against critical functions in the tested entity. IT systems are tested in production environments and testing is known to only a few people at the entity. Testing is thus realistic and gives the entity the opportunity to learn about its readiness to respond to sophisticated cyberattacks. Throughout the testing, risk assessments are conducted with appurtenant measures to safeguard stable operations. After testing is completed, insight gained provides the basis for becoming better equipped to withstand future cyberattacks.

A dedicated team in Norges Bank provides advice and follows up the tests, which are owned and performed by the entity itself.

TIBER tests help to strengthen the resilience of critical financial system functions by improving cyber resilience. The Norwegian implementation of TIBER-EU, TIBER-NO, is based on a framework drawn up by the ECB and has been developed by Finanstilsynet and Norges Bank, in consultation with the financial industry and other relevant authorities.

For more information on TIBER, see https://www.norges-bank.no/tiber.

Cross-border Nordic-Baltic exercise to strengthen contingency arrangements

Norges Bank, together with the Ministry of Finance and Finanstilsynet, participated in a Nordic-Baltic cybersecurity exercise in Helsinki in August 2023. Participants included financial and cybersecurity authorities from Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Estonia and the US. The Finnish authorities initiated the exercise.4

The purpose of the exercise was to improve contingency arrangements in the Nordic and Baltic countries by practising business continuity and intergovernmental coordination and communication. The exercise scenario included cyberattacks on the financial sector and attacks on critical telecommunications infrastructure. The exercise provided useful insights for the participants.

Working group to assess whether there is a need to strengthen contingency arrangements in the payment system

Well-functioning contingency arrangements in the payment system are needed. Norges Bank has previously stated that it should be assessed whether there is a need for contingency arrangements, other than cash, that are more independent of the ordinary payment system. Such arrangements would then come in addition to the continuity and contingency arrangements of individual FMIs (see Financial Infrastructure Report 2023).5

In the Official Norwegian Report (NOU 2023:17), the Total Preparedness Commission recommended that it is “important to plan for rare crisis scenarios, such as the failure of electronic infrastructure over a long period whereby alternative solutions must be used” (Section 27.5.1). The Commission also recommended to “clarify appropriate contingency preparedness in the event of the disruption or failure of payment systems, including cash contingency arrangements and other payment solutions” (Section 27.5.5).

Upon the recommendation of Norges Bank, in November 2023, the Ministry of Finance laid down a mandate for a working group to assess whether there is a need to strengthen contingency arrangements in the payment system. The working group is led by Norges Bank and comprises members from the banking industry and the public sector. The working group is to deliver three interim reports to the Ministry of Finance in the course of 2024:

1. The working group will describe different payment solutions and detect payment system vulnerabilities and scenarios that may affect the ability to make and settle payments, and also identify whether there are alternative payment solutions that could function as contingency arrangements.

2. The working group will assess various measures to enhance the safety of payment transactions, including the need for independent solutions.

3. The working group will propose a specific plan for the execution and follow up of the proposed measures.

Development of method to improve ICT risk assessments that may affect financial stability

With the increasing digitalisation of payments, ICT risk has risen. Owing to a more evolved threat landscape and more complex digital interdependencies in the financial infrastructure, Norges Bank has noted an increased need for enhancing systemic ICT risk competence and methodologies that can better identify such risk.

Finanstilsynet and Norges Bank collaborate to develop a framework for assessing systemic ICT risk in the financial system. Other financial sector entities have been invited to participate, initially to develop the framework and then to help conduct the assessments.

Box 1.2 New regulations help strengthen financial sector resilience

The financial sector is subject to a number of regulations, many of which are part of EU legislation and apply to Norway under the European Economic Area (EEA) Agreement. New regulations are being introduced and are expected to help improve FMI resilience in Norway. Below is an overview of some of the key initiatives in addition to DORA (see box 1.3).

New electronic communications act proposed. The bill was submitted to the Storting (Norwegian parliament) on 12 April 2024. The bill entails the expansion of adequate security requirements for electronic communication providers, comprising data centre operators, and the introduction of a duty to register information related to ownership and services provided. A clearer framework for data centres may help to increase security in the financial infrastructure.

New Act relating to investment control recommended in Official Norwegian Reports (NOU 2023:28) Investeringskontroll – En åpen økonomi i usikre tider [Investment control – An open economy in uncertain times] (in Norwegian only) on 4 December 2023. The Norwegian Investment Control Committee recommended the establishment of a notification scheme for foreign investment in security-sensitive sectors, to be regulated by a new separate investment control act. This will result in a better overview of foreign investment and may help improve risk assessments.

Amendment of the Norwegian Security Act on 1 July 2023. The purpose of the amendments to Section 10 related to ownership control is to strengthen the control of acquisitions that may be contrary to national security interests, for example a number of acquisitions will be subject to the notification duty.

New Act relating to digital security (Digital Security Act) approved by the Storting in December 2023. The EU NIS directive (NIS1) applies in Norway through this Act. The Act sets requirements for digital security and notification of incidents for entities that play a particularly important role in maintaining critical social and economic activity. The Act is wide-ranging and may help to enhance cross-sectoral security. The Act has not yet entered into force.

NIS 2 “The Directive on measures for a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union” (the NIS 2 Directive). The NIS 2 directive was adopted in the EU on 14 December 2022 and will replace NIS 1 in member countries by 24 October 2024. NIS2 entails a substantial expansion of NIS1, with stricter requirements related to security, supervision, sanctions and reporting. NIS2 is considered to be EEA-relevant and is expected to become transposed into Norwegian law.

The Critical Entities Resilience (CER) Directive is considered to be EEA-relevant and is expected to be transposed into Norwegian law further out. The introduction of CER will impose requirements on entities upon which the financial sector is dependent and help strengthen financial sector resilience. CER will be transposed into national legislation in all EU countries by 18 October 2024. No position memo has been published so far for Norway. CER will likely simplify and improve the opportunities of owners of Norwegian FMIs to govern and control foreign providers.

Markets in crypto-assets regulation (MiCA). See Section 4 on crypto-assets.

Box 1.3 Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA)

The Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA) is a regulation adopted by the EU to strengthen ICT resilience in the financial sector, both operationally and in the event of cyberattacks.

DORA imposes requirements related to incident management, supplier management, risk assessment and threat intelligence-based security testing. The DORA requirements are largely in line with best practice in these areas and will, in many cases, replace the prevailing ICT regulation. The purpose of DORA is to strengthen resilience against cyberattacks and other ICT operational incidents.

For banks and other institutions responsible for critical financial system functions, DORA sets requirements for advanced security testing. TIBER is an established framework for such testing and has been essential in the preparation of DORA requirements for this area.

DORA has been adopted by the EU as a regulation and is considered EEA-relevant and will be transposed into Norwegian law. DORA will enter into force in the EU on 17 January 2025. It has not yet been decided when DORA will be applicable in Norway.

4 The Finnish government (2023).

5 Norges Bank (2023b).

2. Central bank money and settlement

Norges Bank is responsible for facilitating a stable and efficient system for payment, clearing and settlement between entities with accounts at Norges Bank. In addition, Norges Bank has a responsibility to issue central bank money in the form of banknotes and coins and ensure that they can efficiently fulfil their function as a means of payment. To ensure that these areas of responsibility are safeguarded in a way that promotes an efficient and secure payment system, both in the present and going forward, Norges Bank is adopting a multifaceted approach. In addition to investigating a future design for the settlement system and real-time payments, the Bank is working to strengthen cash contingency arrangements and is exploring a possible central bank digital currency.

2.1 The settlement system

The operation of Norges Banks settlement system (NBO) is reliable and stable. Norges Bank is responsible for ensuring that NOK will continue to be a secure and efficient means of payment in the future. To develop the settlement system further, Norges Bank is concentrating on three specific areas: adoption of the ISO 20022 international messaging standard for payments, research into the next generation settlement system and the future infrastructure for the settlement of real-time payments.

The current settlement system

In NBO, payments are settled between banks and other institutions in the financial sector that have an account at Norges Bank. NBO is the core of the Norwegian payment system, and the vast majority of payments in NOK are settled with finality in NBO.

The current NBO was introduced in 2009 and consists of the core system (RTGS system)6 for the execution of payment settlement instructions and a system that manages the banks’ collateral for loans (SIL). The global SWIFT network is used as the main channel for payment instructions and other financial messages.

The operation of NBO is secure and stable. Throughout 2023, an average of NOK 355bn in payment transactions was settled daily. At year-end 2023, the banks had sight deposits and reserve deposits in NBO totalling NOK 38bn.

In accordance with the Central Bank Act, Norges Bank must facilitate the central settlement system. This means that Norges Bank is also responsible for the further development of the settlement system such that NOK will continue to be a secure and efficient means of payment in the future. In the assessment of the future payment system, consideration must be given to technological developments, increased complexity in the payments market and an increased level of cross-border payment activity. This makes international harmonisation an important factor in being able to provide efficient settlement services.

To develop the settlement system further, Norges Bank is concentrating on three specific areas: adaptation to the ISO 20022 international messaging standard for payments, research into the next generation settlement system and the future infrastructure for the settlement of real-time payments in Norway.

New messaging standard – ISO 20022

In 2018, the board of directors at the international messaging system, SWIFT, decided that several of the current SWIFT FIN messages should be replaced with the ISO 20022 standard. NBO is based on the SWIFT network and SWIFT’s standard for payment messages for the exchange of settlement instructions with participants in NBO. ISO 20022 is an international messaging standard for payment processing, which replaces old, national and proprietary formats and standards for payment messages. ISO 20022 will enable messages to be sent across different financial market infrastructures (FMIs), increase cross-border standardisation and meet regulatory requirements such as those for anti-money laundering. In addition, the ISO 20022 format is more structured, and the messages can contain more information to facilitate increased automation in payment processing.

Since 2020, Norges Bank has been working on transitioning to the ISO 20022 format in NBO. The ISO 20022 standard that will be used in NBO is developed in collaboration with the banking industry, the Swedish and Icelandic central banks and the settlement system service providers.

Adaptations to the new ISO 20022 format will be made together with a more extensive NBO update. During 2024, the adaptations will be tested internally and in collaboration with participants in NBO. This is a comprehensive project, both for Norges Bank and the banking industry. Restructuring to use the ISO 20022 format in Norwegian, Danish, and Swedish settlement systems will be made in parallel. Norges Bank plans to start using the ISO 20022 format for payment messages in NBO from March 2025.

Assessment of the next generation settlement system

At present, NBO functions reliably. It should also do so in the future. Technological advances and changes in the settlement systems of collaborating countries mean that it is appropriate to begin the process of overhauling the payment system. Norges Bank has therefore begun researching the next generation settlement system as a part of its strategic goals under Strategy 25.

Two alternative models are being examined in the Bank’s research: a separate dedicated platform for payment settlement at Norges Bank and the real-time gross settlement (RTGS) system owned and operated by the Eurosystem.

Until now, Denmark and Sweden have had the same RTGS service provider as Norway. While Denmark has decided to participate in T2, Sweden will decide over the summer whether Riksbanken should initiate formal discussions with the Eurosystem on participation in T2 and the securities settlement system, T2S (see box 2.1). This means that Norges Bank’s collaboration with Riksbanken and Nationalbanken will change, for example concerning the joint follow-up and risk management of international service providers.

A separate dedicated platform for Norges Bank entails a settlement system established and operated on dedicated hardware for Norges Bank, as is currently the case. With this solution, Norges Bank itself will design the settlement system and be responsible for operations, development, security and following up service providers.

Upon participating in T2, Norges Bank will continue to make decisions regarding settlement in NOK, decide which financial institutions participate in settlement and retain complete control over liquidity management and monetary policy. Norges Bank will not be able to make decisions concerning the platform alone but can influence assessments through participation in the Eurosystem platform’s governance structure. Collaboration between the participating central banks enables the use of significant resources for developing the platform in areas including security, continuity and preparedness.

In assessing the alternatives, Norges Bank will take into account changes in needs since today’s NBO was introduced. For example, the Nordic market is affected by European financial sector regulation and Nordic participants will need to meet a more integrated payment landscape in Euro area countries. Another aspect to be considered is the aggravated geopolitical situation and an increased need for contingency arrangements and cyber security. Weight is also given to the solid foundation that the settlement system provides both public and private institutions so they can advance and provide modern payment services. The various alternatives will be assessed according to international principles and requirements in the Security Act. In collaboration with Euronext Securities Oslo (ES-OSL), Norges Bank is also considering whether possible participation in the Eurosystem platform should include T2S.

The current settlement system reliably meets the needs for settlement services in Norway. The solution is operated on a modern and secure platform and in accordance with international standards and recommendations, and all parts of its operation are followed up by an organisation established and adapted by Norges Bank. The assessment of the alternatives is underpinned by the fact that Norges Bank has the foundation and experience to be able to continue operating the settlement system on its own dedicated platform.

Box 2.1 The Eurosystem’s platform for settlement services

TARGET Services are a number of services developed and operated by the Eurosystem that ensure the free flow of cash, securities and collateral across Europe.

These FMI services include:

T2 Gross settlement of payments equivalent to the Norwegian RTGS

T2S Settlement of securities

TIPS Instant payment settlement service

ECMS A unified system for managing assets used as collateral in Eurosystem credit operations (only for the euro)

Real-time payments in Norway

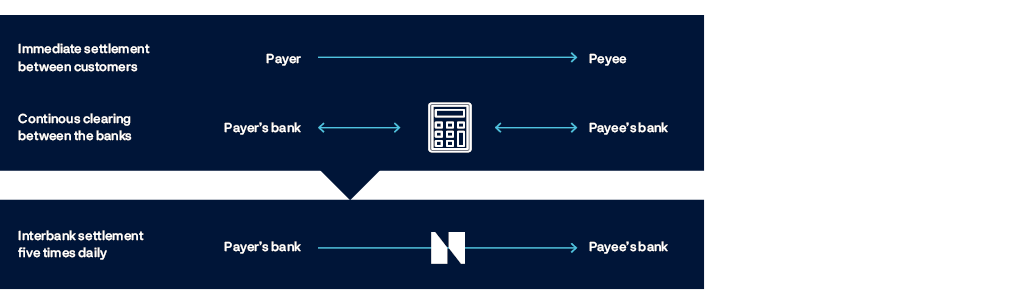

Real-time payments are payments where the funds are available in the payee’s account seconds after the payment is initiated, 24/7/365. A well-functioning system for real-time payments is a key component of an efficient payment system, which is shown through increasing volume in recent years. The importance of real-time payments is also illustrated at the European level, where new regulations require banks and other PSPs that offer traditional credit transfers in EUR to also send and receive real-time payments at the same or a lower price than traditional credit transfers.7

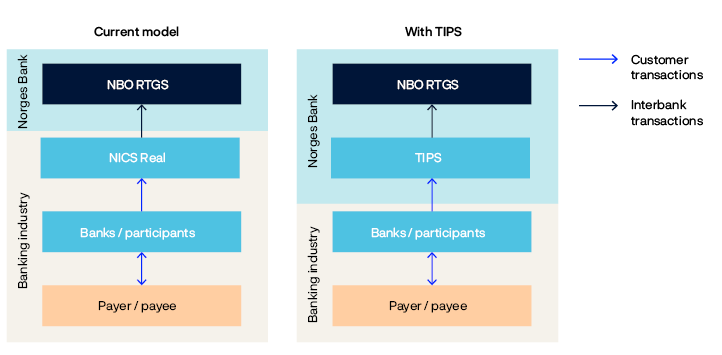

The current real-time payment solution in Norway, NICS Real, is operated by Bits, the financial infrastructure company of the banking industry (see box 2.2 for more information about the solution). In 2020, Norges Bank began a process to assess whether it should establish the underlying infrastructure for real-time gross interbank settlement of retail payments in central bank money.

Box 2.2 NICS Real, the Norwegian real-time payment solution

In 2013, the banking industry established a real-time payment solution in Norway through Bits, the financial infrastructure company of the banking industry. The solution enabled funds to be immediately available to recipients immediately. However, the solution was not completely satisfactory as the banks were exposed to credit risk due to settlement between the banks occurring after the funds were made available to the payee.

Following an initiative from Norges Bank, the banking industry (through Bits) established NICS Real, an improved real-time payment solution in 2020. The solution has collateral for settlement, and messages are exchanged in accordance with the ISO 20022 international messaging standard.

The current Norwegian solution entails that the banks set aside liquidity in NBO as collateral for settlement of payments cleared in NICS Real, so that settlement between customers of different banks can occur immediately. NICS Real operates stable services and has a high degree of availability.

Box 2.3 TIPS, the Eurosystem’s platform for real time payments

TARGET Instant Payment Settlement (TIPS) was launched as an infrastructure service for instant payments in November 2018.

TIPS was developed as an extension of TARGET2 (now replaced by T2) and settles instant payments individually in central bank money. TIPS settles payments in EUR and SEK. DKK will be settled in TIPS from April 2025.

TIPS is adapted to the ISO 20022 format.

In its 2021 consultation response, the banking industry supported Norges Banks intention to enter into formal discussions with the European Central Bank (ECB) concerning TIPS participation.

Since the beginning of 2022, Norges Bank has been in formal dialogue with the ECB, with the aim of providing a basis for a decision on participation in TIPS and a currency participation agreement with the ECB.

The TIPS solution has been assessed in detail, including technical set-up, security, contingency arrangements and costs. In dialogue with the ECB, Norges Bank has placed emphasis on ensuring that TIPS supports Norwegian needs and requirements in a number of areas, including the need for adjustments to TIPS to allow for one bank to choose another as a settlement bank. If TIPS is established together with the current settlement system, there is also a need for adaptations to secure information sharing between the two systems. As part of the process, Norges Bank has also reviewed the ECB’s standard Currency Participation Agreement for countries that do not use the euro, including Sweden and Denmark. This Agreement must meet the needs of Norges Bank and other relevant stakeholders.

In the event of a transition to TIPS, Norwegian banks will have access to the same ireal-time payment nfrastructure as banks in the other Nordic countries. The work is nearing completion.

The Eurosystem has established a strategic roadmap for TIPS and is continuously exploring new functionalities. The Eurosystem is examining, inter alia, the functionality of bulk payments with the possibility of submitting a file with several individual payments, which can either be settled immediately or within a given timeframe. Another strategic focus area is cross-border and cross-currency payments. A number of initiatives are underway that together will simplify cross-border and cross-currency payments: i) to establish the functionality for making payments between currencies available in TIPS, ii) to establish TIPS as a central hub linked to other real-time payment systems in Europe for the euro and iii) to establish links to non-euro real-time payment systems both in and outside Europe.

Technically and functionally, both NICS Real and TIPS are secure, efficient and modern underlying infrastructures for the payment solutions offered to the general public. Banks and other PSPs must develop and offer retail services that can be used by private individuals, businesses and government agencies based on the opportunities afforded by the infrastructure, regardless of the underlying infrastructure used for real-time payments in Norway in the future. Real-time payments will be one of the topics in the payment forum (see box 2.4).

Box 2.4 Establishment of a payment forum

Norges Bank has taken the initiative to establish a Norwegian payment forum. The forum is intended to be an arena for exchanging information and discussing measures and strategies that contribute to the development of the payment system in Norway and abroad. Norges Bank’s work on the next generation settlement system, real-time payments and central bank digital currency will be among the topics discussed in the forum.

Key stakeholders in the payment system in Norway have been invited to participate, including PSPs, FMIs, representatives of end-users and public authorities. The forum does not make decisions, has no operational role and does not issue statements that bind participants. The forum’s activities are delimited by other bodies, including in the field of security and contingency preparedness. The forum is scheduled to meet twice per year. The first meeting will be in June this year. Minutes of the meetings will be made publicly available on Norges Bank’s website. The forum bears a resemblance to advisory bodies on payments in other Nordic countries.

6 Real Time Gross Settlement.

7 Regulation (EU) 2024/886 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 March 2024 amending Regulations (EU) No 260/2012 and (EU) 2021/1230 and Directives 98/26/EC and (EU) 2015/2366 as regards instant credit transfers in euro.

2.2 Cash still plays an important role in the payment system

Cash usage in Norway is among the lowest in the world. Increased use of electronic payment methods is highly advantageous for banks and their customers, and for society as a whole. There is still a need for cash. Cash is not an end in itself, but has characteristics that other means of payment and instruments do not have and that are important for ensuring an efficient and secure payment system. Cash is crucial for contingency considerations and for financial inclusion. It also provides the general public with access to central bank money. For cash to fulfil its functions, it must be sufficiently available and easy to use. Developments over time have shown that this is not ensured by the market alone. Regulation is therefore necessary, even if it entails costs.

Cash usage is low

The share of cash payments at points of sale (POS) and between private individuals (person-to-person) has declined over many years. The cash share declined further in 2020 at the outset of the pandemic and has since remained fairly stable at around 3%. The amount of cash in circulation fell by approximately 20% in the period between 2016 and 2021 and remained fairly stable thereafter at a level accounting for around 1.4% of narrow money (M1). This makes Norway one of the countries with the lowest cash usage in the world. Low cash usage may entail a wider difference in the need for cash in normal and contingency situations where cash must replace some of the electronic payments. If the capacity of cash infrastructure is insufficient in normal situations, it could also entail difficulties for cash use as a contingency solution.

Maintaining the cash infrastructure necessary for cash to be sufficiently available and easy to use entails costs. The total social costs related to cash have declined, owing to both increased efficiency and reduced usage. Since cash usage has fallen substantially and a large share of costs are fixed, the social cost per cash payment has increased markedly and is high. Norges Bank has calculated the unit cost of cash payments, NOK 19.2 in 2020.8 The figure includes all cash-related costs, in addition to actual payment costs, (including time use for payer and payee), cash infrastructure costs (deposits and withdrawals and other cash services) and Norges Bank’s production and issuance costs are included.

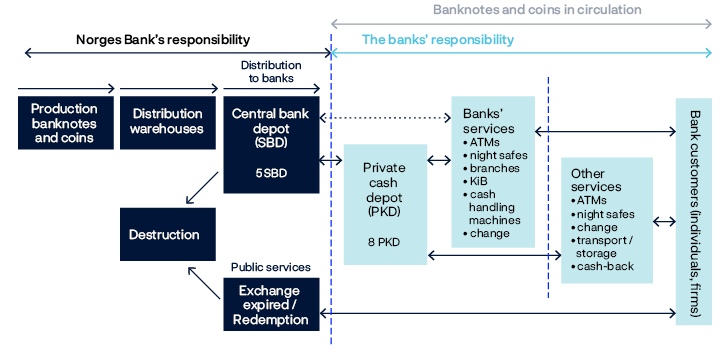

Norges Bank has strengthened its cash contingency arrangements

Norges Bank is responsible for supplying banks with cash and meeting the public’s demand for cash, even in contingency and crisis situations. Based on the intensified risks, expanded threat landscape and new developments, Norges Bank has adjusted and strengthened its cash-related contingency arrangements so that it will be able to meet banks’ demand for cash in different situations that may arise in the future. For cash to reach the general public, banks must also have adequate contingency arrangements in place.

Banks must provide their customers with cash services in both normal and contingency situations

Banks have a legal obligation to provide their customers with the possibility to make cash deposits and withdrawals in line with customers’ expectations and needs. The obligation also applies in situations when demand for cash rises, such as when electronic payment systems are disrupted. This can be under the auspices of the banks themselves or through agreement with other cash service providers.9 The obligation covers withdrawal and deposit services for both private individuals and firms. Banks currently offer cash withdrawals through in-store cash services (KiB) and ATMs, while deposits are made through KiB or in banks’ deposit machines. Some banks also offer cash services at bank branches. In addition, cash can be obtained through ATMs owned by others, mainly Nokas Verdihandtering AS (Nokas) and Loomis Norway,10 and via cash-back, a voluntary arrangement provided by shops, where customers can withdraw cash in connection with goods purchases. Firms with larger cash volumes require separate arrangements.

The KiB in-store cash service now accounts for a substantial portion of banks’ cash services. The service is available in approximately 1450 of Norgesgruppen’s shops with over 90 banks in Norway participating.11 While the solution mainly provides most customers with an adequate service, it is only available to BankAxept card holders. It also fails to cover the business sector’s need for change and to make larger cash deposits.

BankAxept has established a backup solution that kicks in, for example, in the event of poor communications with merchants. Merchants with terminals that accept the BankAxept backup solution receive a settlement guarantee for all sales within the first six hours of a disruption when a BankAxept card is used. A number of chains that sell basic necessities, such as grocery stores, pharmacies and petrol stations, have the option of using terminals with an expanded back-up solution that provides merchants with a seven-day settlement guarantee for sales in the event of a disruption in communications. KiB is not part of this contingency solution, which means that a large part of the ordinary cash supply will be disrupted in situations where the backup solution has kicked in. Pressure could then mount on other parts of the cash infrastructure even without an increased total demand for cash. The KiB service could function as part of banks’ cash contingency plans if backup solutions are expanded to include KiB cash withdrawals (and deposits). This could also boost the efficiency of cash circulation in a contingency situation.

The cash handling companies Nokas and Loomis play a key role in the cash supply chain. They account for most cash handling between central bank depots and public services and the services they provide to banks and other customers include transportation, storage, counting, quality control, sorting and packing. They also handle account transactions. The functioning of this part of the cash supply chain is a prerequisite for banks to fulfil their obligations. Banks must be prepared to step in and find new solutions to maintain an adequate supply if these market participants reduce their range of services.

New fee model for ATM withdrawals

For many years, banks have worked together on a regulation related to ATM cash withdrawals using BankAxept cards. The regulation stipulates a standard fee for the withdrawer’s card-issuing bank to pay the ATM owner. For non-bank ATM owners (primarily Nokas and Loomis), related revenues have been limited to the interbank fee. On the other hand, banks have been able to charge their own fees for customer ATM use, which may differ in level from the interbank fee. At the end of 2023, non-bank market participants accounted for just under half of all ATMs.12

In 2008, the interbank fee was reduced to NOK 4.50 and has since remained unchanged. The number of cash withdrawals per ATM has since declined substantially and increased the unit cost of ATM transactions. The operation of many ATMs has therefore become unprofitable, which has resulted in ATM closures and the reduction or absence of ATM services in more remote locations.13

Banks have now chosen to replace the interbank fee with a solution whereby each ATM owner sets prices for withdrawals from their ATMs and charges users directly. This change came into effect on 20 February 2024 and it is now up to each ATM owner/transaction bank to establish a business model to finance ATM operations. The change provides better opportunities for profitable ATM operations, which could thus provide a basis for maintaining more ATMs. Whether users experience price changes depends on the size of ATM owners’ fees and fees charged by users’ banks.

Norges Bank will monitor the impact of the change on developments in the overall provision of cash services, including whether an appropriate infrastructure is maintained with sufficient geographical distribution and at appropriate prices that help ATMs continue to function as a common solution.

Clarifying consumers’ right to pay cash

According to Section 3-5 (1) of the Central Bank Act, notes and coins issued by Norges Bank are legal tender. The provision is waivable, ie parties to the settlement of a payment are free to agree on which means of payment to use. On the other hand, Section 2-1 (3) of the Financial Contracts Act states that a consumer always has the right to settle with the payee in legal tender, ie using notes and coins. For many years, questions have been raised regarding the interpretation of the Section, which has been challenged repeatedly.

On 4 June, the Storting (Norwegian parliament) passed legislative amendments that clarify consumers’ right to pay cash. According to the amendments, consumers will be able to pay with cash at points of sale where a business regularly sells goods or services to consumers, provided that if goods or services can be paid for with other means of payment at the point of sale or in the immediate vicinity. Exceptions are made for sales of goods from vending machines, sales in unmanned sales premises and sales in premises to which only a limited group of persons have access. Furthermore, an amount limit of NOK 20,000 has been set. Separate provisions have also been adopted, so that separate rules can apply for passenger transport services.

Norges Bank is of the opinion that clarification was necessary and that the amendments are appropriate given current circumstances and needs. This is important for ensuring that cash can continue to fulfill its functions. The amendments do not introduce a new obligation but clarify existing obligations. The amendments will thus have limited consequences for firms whose current practices are in line with the clarification. Firms’ costs related to receiving cash will depend, for example, on banks’ provision of cash services. Under Section 16-4 of the Financial Institutions Act and Sections 16-7 and 16-8 of the Financial Institutions Regulation, banks are required to provide their customers with the ability to withdraw and deposit cash in line with customer’s needs and expectations.

Cash and crime

While cash plays an important role in society, the fact that it offers anonymity and leaves no electronic traces are characteristics that can be, and are, abused in connection with different types of crime, such as money laundering. When combatting economic crime, it is also crucial to not hinder cash from fulfilling its important role. Both of these considerations must be taken into account in the formulation of regulations and guidelines related to the use of cash.

Box 2.5 Public commission tasked with exploring secure and simple payments for all, including the importance of cash

In May 2023, a commission was appointed to explore future secure and simple payments for all. A substantial part of the mandate involves assessing the importance of cash for an efficient and secure payment system and what cash means for financial inclusion and contingency arrangements. The commission will also assess whether there is a need for measures that can “ensure financial inclusion and the right to pay cash”, as well as a need for measures that can “ensure the role of cash as a contingency solution, for example by ensuring that withdrawals and payments with cash can be carried out to a greater extent without dependence on vulnerable electronic systems and liability in the event of various degrees of disruption in the payment infrastructure”.

The commission will also “describe and assess how secure and simple payments for all can be safeguarded and developed through cash and other solutions in the longer term”.

The commission will submit its report to the Ministry of Finance by 15 November 2024.

8 See Norges Bank (2022a). Calculations of cash-related costs are uncertain. A large share of cash usage must be estimated. Furthermore, different methods and the choice of assumptions related to included costs and their distribution will generate different results.

9 Section 16-4 of the Financial Institutions Act and Sections 16-7 and 16-8 of the Financial Institutions Regulation.

10 At end-2023, banks owned slightly more than half of all ATMs, while the rest are non-bank owned, mainly Nokas and Loomis Norge.

11 For a broader discussion of in-store cash services, see eg Norges Bank (2021).

12 Includes both ATMs and cash recycling machines.

13 See eg Finance Norway (2024).

2.3 Norges Bank’s research on central bank digital currency

Norges Bank is assessing whether a central bank digital currency (CBDC) is a suitable instrument for ensuring access to a means of settlement trusted by all, also in new payment arenas, promoting responsible innovation and improving payment contingency arrangements. Both retail and wholesale CBDCs are being examined. Tokenisation and settlement solutions in central bank money have received growing attention internationally. In 2023, Norges Bank concluded an exploratory phase including eg experimental testing of different technical solutions and analyses of payment system scenarios. In the period to 2025, Norges Bank will analyse the possibilities afforded by a CBDC and the ramifications of introducing different forms of CBDC, and will test and evaluate candidate solutions. As global work on CBDCs is still in a phase marked by experimentation and impact assessments, more knowledge, collaboration and standardisation is needed.

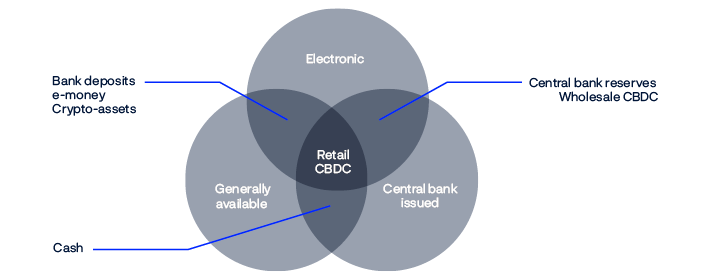

What is a central bank digital currency?

CBDC is electronic money issued by the central bank in the official unit of account. Internationally, two main variants of CBDC are being studied: retail CBDC and wholesale CBDC.

Retail CBDC is generally accessible to the public on par with cash and bank deposits. Unlike cash, they are electronic and unlike bank deposits, they are issued by a central bank (Chart 2.3). Banks and other third parties will have the possibility to develop and offer payment services to private individuals, companies and the public sector using retail CBDC as their underlying means of payment.

Wholesale CBDC is central bank reserves in tokenised form. Tokenisation is a process of representing assets in a form that allows the programming of transactions to take place when specific events occur (see box 2.4). Wholesale CBDC is not intended for the general public and would only be available to banks and some other FMIs with an account in the central bank, equivalent to current interbank settlements but in a different technological form. Such CBDCs can be a secure means of settlement between banks in transfers and the trading of tokenised money, securities and other assets.

Box 2.6 Tokens and tokenisation

Tokenisation is a process of representing claims/assets so they can be traded using distributed ledger technology (DLT) or on other programmable platforms. Tokens can represent assets that are already registered on a traditional database. Tokens can also be issued directly on a programmable platform without first existing externally (so-called ”native tokens”). These can be financial assets such as different types of money and securities or other assets such as real estate.1

Tokenisation allows the programming of transactions to take place when specific events occur. Programming takes place in smart contracts. These are digital algorithms that link one or more conditions in order to automate transactions. One example is “atomic settlement” (also known as DvP – Delivery versus Payment), where the transfer of an asset’s ownership and the payment occur simultaneously and are mutually conditional.

Among other things, tokenisation can improve efficiency, reduce some forms of risk, and foster new functionalities and business models. At the same time, there are issues related to regulation and governance, for example.

1 See Aldasoro et al (2023) and BIS (2023) for further discussions on tokens and tokenisation.

The purpose of introducing a form of CBDC depends on the development of the financial sector. In countries with a limited financial sector, the introduction of a retail CBDC could be a measure for promoting financial inclusion among the unbanked and for improving payment system efficiency and economic development.

Norges Bank is assessing whether a Norwegian CBDC is a suitable instrument for ensuring access to a means of settlement trusted by all, also in new payment arenas, and for promoting responsible innovation and improving payment contingency arrangements. A CBDC can promote the use of new technology for developing new and attractive payment solutions in NOK. In order for CBDC-based payment solutions to strengthen contingency arrangements in the payment system, the CBDC system must function independently of banks’ payment systems. CBDC’s can also have other economic benefits, including a function as legal tender.

Development of retail CBDC in other countries

So far, only a few central banks in developing countries and emerging economies have introduced a retail CBDC. Surveys conducted by the BIS show that almost all central banks are studying CBDCs,14 with focus typically being given to the objectives and ramifications of introducing a CBDC, necessary characteristics and legal implications. A number of central banks have developed simple test versions to increase their knowledge about different technological solutions and how these might help meet objectives.

The ECB is likely the central bank in advanced economies that has made the most progress in retail CBDCs. In autumn 2023, the Executive Board of the ECB decided to continue its work on the digital euro in a preparatory phase, which was planned to continue until 1 November 2025. The ECB will further examine the specific design of the digital euro system and prepare for the construction of a technical infrastructure. The ECB has put framework agreements out to tender for the procurement of several components of the technical solution. In this phase, the ECB will also establish a set of rules for the use of payment solutions based on a CBDC. The ECB aims to decide whether to adopt the digital euro after the end of the preparatory phase. At the same time, the EU is preparing legislative amendments necessary for the introduction of the digital euro.15

In February 2023, the Bank of England, together with HM Treasury, published a consultation paper on a digital pound and announced that a digital pound would likely be needed in the future. Many respondents were concerned about the possibility of anonymous payments. The Bank of England and HM Treasury will continue their research on a digital pound and have announced more consultations.16

Sveriges Riksbank, the Federal Reserve, Bank of Canada, Reserve Bank of Australia and Bank of Japan are examples of other central banks that are exploring CBDCs. International organisations such as the IMF and the BIS are also devoting considerable resources to analysing different issues related to CBDCs. The BIS Innovation Hub has been established to experiment with ways in which new technology can strengthen the financial system, with CBDC as a key theme.

Studies of wholesale CBDCs

So far, no central bank has introduced ordinary settlement with tokenised central bank reserves. The Eurosystem, Bank of England and several other central banks are investigating how transactions in central bank money can best be settled on tokenised platforms. The purpose is, among other things, to facilitate innovation in the payment and financial system in a secure and efficient manner. One feature that is being tested is that the payment and transfer of ownership related to trading in securities or other assets represented on tokenised platforms are mutually conditional in a way that is efficient and reduces settlement risk.17

Both arrangements for settlement with tokenised central bank reserves and adjustments to the ordinary settlement system may be relevant. The progress of work on such solutions will depend, inter alia on developments in the tokenisation of money and other assets such as securities.

Norges Bank is moving ahead in its CBDC study

Norges Bank has explored CBDCs since 2016. Low cash usage, new technological opportunities and prospects for the establishment of new private money and payment systems are an important motivation driving this study. The main question is whether the introduction of a retail and/or wholesale CBDC is necessary to ensure that the Norwegian krone is a secure, efficient and attractive means of payment in the future too. As part of the study, consideration is also given to whether other measures, such as different forms of regulation and the development of other payment systems, are better suited to achieving objectives.

In the period between 2021 and 2023, Norges Bank completed a phase of its exploration project consisting of experimental testing of technical solutions, analyses of scenarios for the payment system, evaluation of consequences for liquidity management and monetary policy, and a review of the legislative changes necessary for an introduction of CBDC.

The research phase is summarised in Norges Bank (2023c).18 The purpose of the scenario analysis was to shed light on whether developments related to new types of monetary and payment systems and financial actors may be part of the motivation for introducing a CBDC. The working group identified some developments that may entail challenges in Norges Bank’s areas of responsibility. In the group’s assessment, however, such considerations alone suggest that introducing a retail CBDC is not an urgent matter. It is also uncertain whether a retail CBDC is the most adequate instrument for managing risks in Norges Bank’s areas of responsibility related to new monetary and payment systems.

The ongoing research phase started in the autumn of 2023 and will last until 2025. The main delivery will be a decision basis for, and an assessment of, whether Norges Bank should advise introducing a CBDC and, if so, the recommended type of design.

In the current phase, Norges Bank will explore how a CBDC solution should be designed, what uses it aims to satisfy and how different stakeholders should be motivated to provide the solution with the desired applications and distribution. The study is based on the premise that banks and other payment service providers will develop CBDC-based retail payment services. This means that payment-related control functions will also be the responsibility of payment service providers. Norges Bank will have neither direct contact with end-users nor access to information related to users' CBDC payments.

Wholesale CBDC has been given greater focus in the study than in previous phases. Norges Bank is investigating solutions for settlement of payments and trading on tokenised platforms in central bank money and the ramifications for Norges Bank’s areas of responsibility. Tokenisation in the financial system and settlement in central bank money have received growing attention internationally.19 At the same time, it is uncertain whether and how quickly tokenisation will spread.

Norges Bank is continuing experimental testing of technical solutions in order to clarify the extent to which necessary CBDC characteristics can be achieved. The Bank has also had sandboxes developed for core retail and wholesale CBDC infrastructures. Banks and other stakeholders are invited to participate in the testing of different CBDC aspects.

Norges Bank is also in contact with other central banks and international organisations that study CBDCs and the Bank benefits from the exchange of information and analyses. As global work on a CBDC is still in a relatively early phase, more knowledge, collaboration and standardisation are needed.

Any introduction of CBDC depends on considerable participation from other payment system stakeholders, and many external financial actors will be affected. CBDCs will be one topic in the new payment forum (see box 2.4).

14 Kosse and Mattei (2023)

15 ECB (2023a).

16 Bank of England and HM Treasury (2023) and Bank of England and HM Treasury (2024).

17 ECB (2023b) and Swiss National Bank (2023).

18 Parts of the study phase are documented in more detail in Norges Bank (2023d), Syrstad (2023) and Bernhardsen and Kloster (2023). See also Alstadheim (2023).

19 BIS (2023).

3. Payment costs

Costs in the Norwegian payment system are low by international standards. The rising use of mobile payments with international cards at physical points of sale is pushing up payment costs. It is important for cost efficiency that the payment card with the lowest costs – the national debit card BankAxept – is also made available for mobile payments. Merchants should be able to preselect the card network to be used for mobile payments with co-badged cards in the same way as for payments with physical cards, but the payer must also be given a real option to override the merchant’s selection. There have been a number of cases of billing fees materially exceeding the cost of issuing a bill. Some billers have recently reduced their fees. Letters and statements from the Norwegian Consumer Authority may mean that other billers also reduce their fees. If not, the authorities may consider regulations putting an explicit cap on billing fees.

3.1 Payments at points of sale

Increased use of payment cards in mobile phones

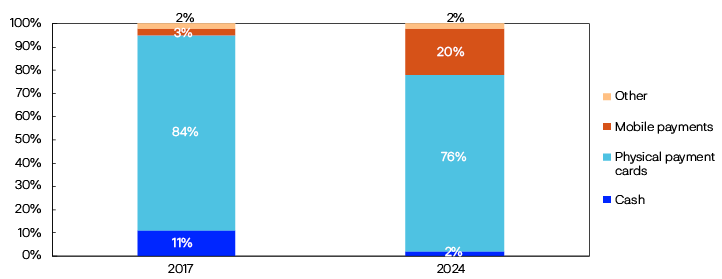

Norges Bank has conducted annual surveys of households’ payment habits since 2017. Chart 3.1 shows developments in the means of payment used at points of sale.20

The share of cash payments at points of sale fell sharply during the pandemic and is now just 2%. The share of payments with physical payment cards has also declined somewhat in recent years, but they remain the dominant means of payment. The share of mobile payments has grown markedly and is now 20%. As mobile payments use a payment card as the underlying payment instrument, the vast majority of payments at physical points of sale are therefore card payments.

Mobile payments at physical points of sale can take different forms:

- One type of mobile payment is made through card terminals using contactless technology, ie near-field communication (NFC), in the same way as with a physical card. The best-known terminal-based solutions are Apple Pay, Google Pay and Samsung Pay.