Financial stability outlook

The Norwegian financial system has weathered the pandemic well. The gradual reopening of society, along with government support measures, has helped keep bank losses low. Financial system vulnerabilities in Norway persist, but have been met by measures to increase resilience. At the same time, the risk of shocks, particularly from abroad, represents a threat to financial stability. Uncertainty regarding the further evolution of the pandemic has diminished since Financial Stability Report 2020, but banks are resilient and have ample capacity to absorb losses.

The recovery is contributing to financial stability

The pandemic resulted in a less pronounced economic downturn and lower bank losses than widely feared last year. Extensive government support measures, good welfare arrangements and an expansionary monetary and fiscal policy have dampened the economic impact of the pandemic. Nevertheless, some households and firms have been hit hard. Bank losses have been limited, thanks to both the support measures and banks’ low exposures to the hardest-hit industries. A resilient banking sector has been crucial for maintaining a well-functioning financial system, and a lower countercyclical capital buffer rate gave banks greater space to extend credit through a period of considerable uncertainty. Norges Bank’s extraordinary liquidity measures and foreign exchange market interventions helped dampen the turbulence so that financial markets functioned better. The measures also eased bank funding and countered an undesirable credit tightening, which could have amplified the downturn. Against the background of the recovery over the past year, Norges Bank now assesses the overall financial stability outlook as little changed since before the pandemic hit.

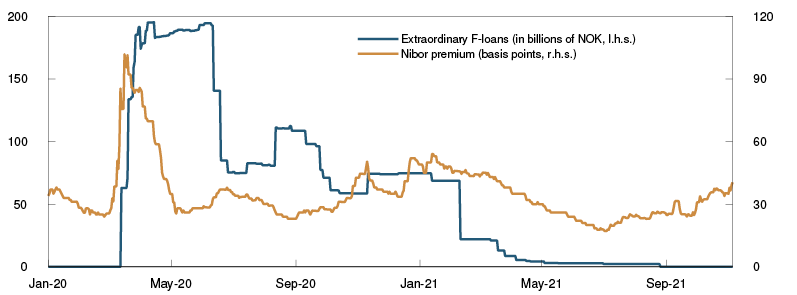

The reopening of society has resulted in a marked upswing in the Norwegian economy, and activity is now higher than before the pandemic. A gradual rise in Norges Bank’s policy rate has begun, and increases in the countercyclical capital buffer have been announced. The extraordinary liquidity measures were unwound on the back of an improvement in the functioning of money and credit markets. The last extraordinary loan to banks matured in August 2021. Fiscal policy measures are also being phased out as the economy normalises.

Risk of shocks

Uncertainty about the future evolution of the pandemic is lower than at the time of the 2020 Report. Even so, a resurgence of the pandemic may dampen the economic upturn, weaken business profitability and push up bank losses.

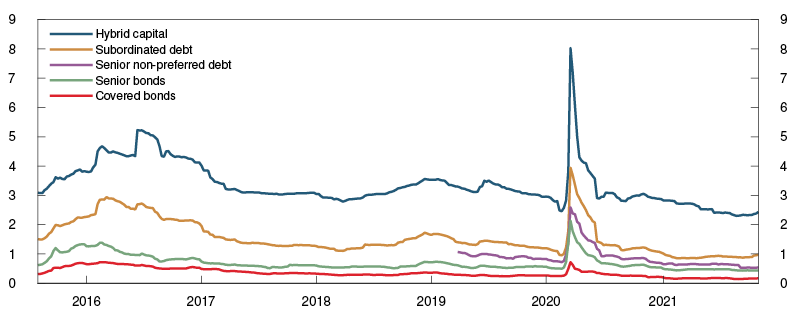

During the years prior to the pandemic, global interest rates were historically low. The pandemic resulted in even more expansionary monetary policy, and extensive fiscal policy measures were introduced. This has supported the economic recovery, but has also reduced many countries’ fiscal and monetary policy space. Persistently low interest rates abroad can also induce market participants to assume greater risk. Global vulnerabilities have built up in the form of increased debt and higher asset prices. Policy rate expectations and long-term interest rates have risen markedly through autum. Expectations of higher inflation and possible monetary tightening globally have likely pushed up market interest rates. Higher interest rates could restrain debt accumulation and asset inflation. This may reduce the build-up of vulnerabilities. A sudden rise in interest rates and risk premiums can lead to stress in the Norwegian financial system, owing to its close interconnectedness with the global economy and financial markets. This interconnectedness came into evidence during the market turbulence at the beginning of the pandemic.

Financial system vulnerabilities persist, but have been met with measures

Financial system vulnerabilities in Norway can lead to shocks having more serious consequences for financial stability. Overall vulnerabilities are assessed as being broadly at the same level as prior to the pandemic.

High household debt has long been the main financial system vulnerability in Norway. Leverage is high both historically and compared with other countries. High debt makes households vulnerable to a loss of income, higher lending rates and a fall in house prices. The risk that many households tighten consumption at the same time constitutes a threat to financial stability. Banks’ high commercial real estate exposures are also a vulnerability that can lead to substantial credit losses if commercial property prices fall, as shown by the stress test in this Report. In addition, banks’ interconnectedness, partly owing to their cross-exposures, can propagate and amplify shocks.

Credit and property and financial asset prices have often shown a pronounced rise ahead of financial crises. Residential and commercial property prices fell during the first phase of the pandemic, but have since risen sharply, as have financial asset prices. Low interest rates over a long period have driven down yields, and risk premiums are now at very low levels. Unexpected events can therefore result in considerable corrections in asset prices. Property price inflation has recently been more moderate. Credit growth picked up somewhat through the pandemic, but has recently levelled off.

Regulations, such as requirements for banks’ capital, liquidity and credit standards, increase bank resilience and reduce vulnerabilities. This helps dampen the impact of shocks and downturns.

In autumn, Norges Bank was given decision-making responsibility for the countercyclical capital buffer and formal advisory responsibility for the systemic risk buffer. These two buffer requirements constitute a significant part of banks’ total capital requirements. The Committee decides on the countercyclical capital buffer rate each quarter and is to advise on the systemic risk buffer at least every other year, for the first time in 2022. In line with Norges Bank’s new areas of responsibility, the Committee will prepare a framework for its advice on the systemic risk buffer in 2022.

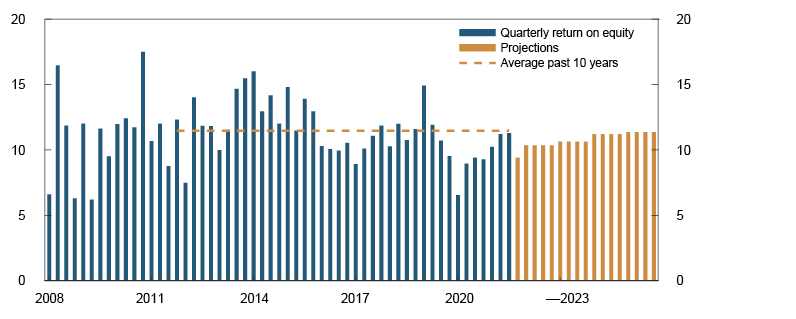

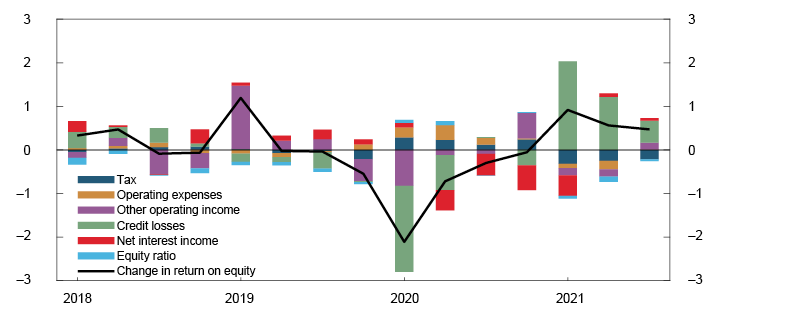

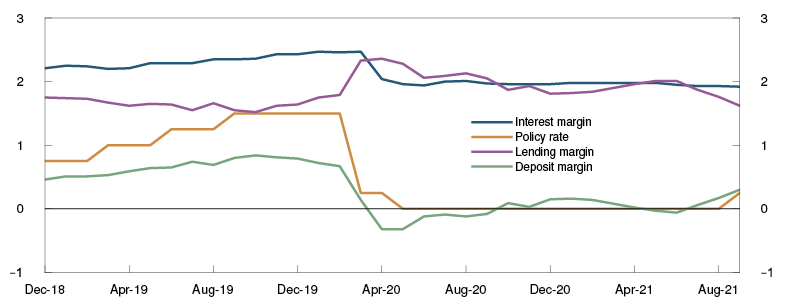

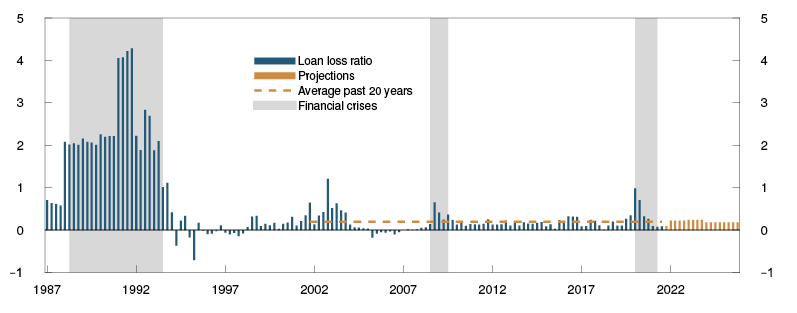

Bank resilience has not weakened during the pandemic

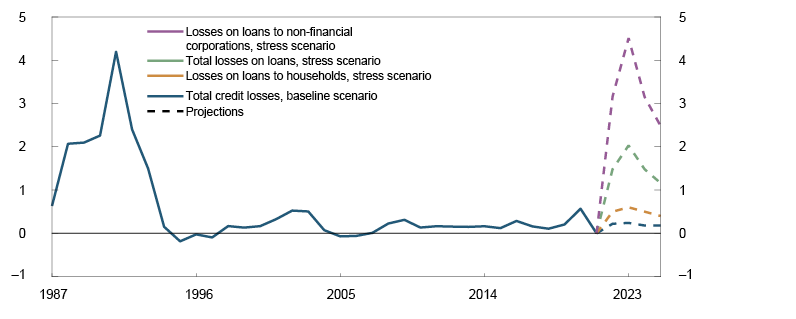

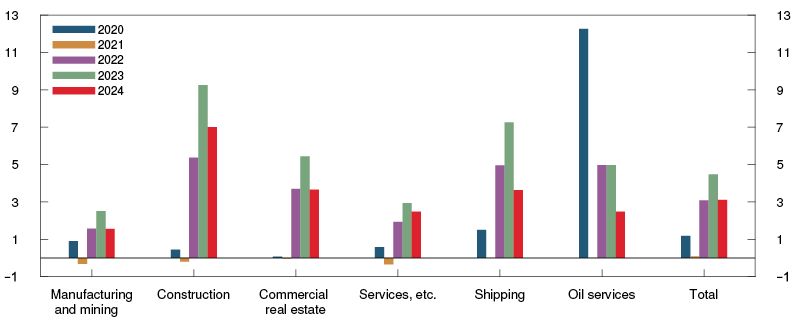

The Norwegian banking sector is solvent and well-equipped to withstand shocks. Bank profitability is solid, and banks’ have ample access to funding. Solid underlying profitability has resulted in earnings sufficient to cover the losses incurred during the pandemic, while increasing lending. In addition, restrictions on dividend distribution have compelled banks to retain more earnings than normal during the pandemic. This has increased equity and thus loss-absorbing capacity. Higher interest rates ahead will improve bank profitability. Losses on corporate loans have declined as the economy improved. There are no signs that the business sector has drawn substantially on its financial buffers, and credit losses are expected to remain low. Even so, owing to the uncertainty about the further evolution of the pandemic, loss prospects are somewhat more uncertain than normal.

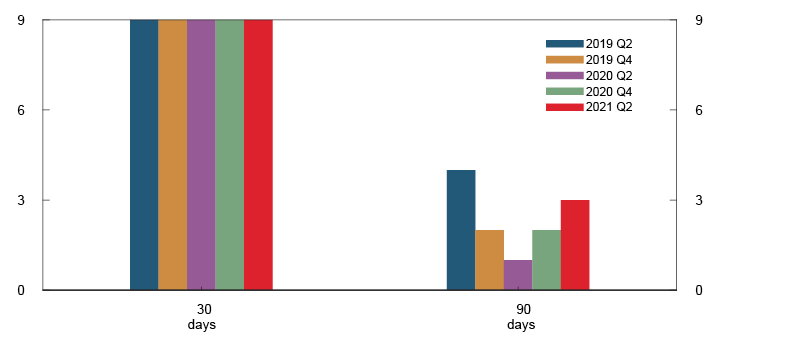

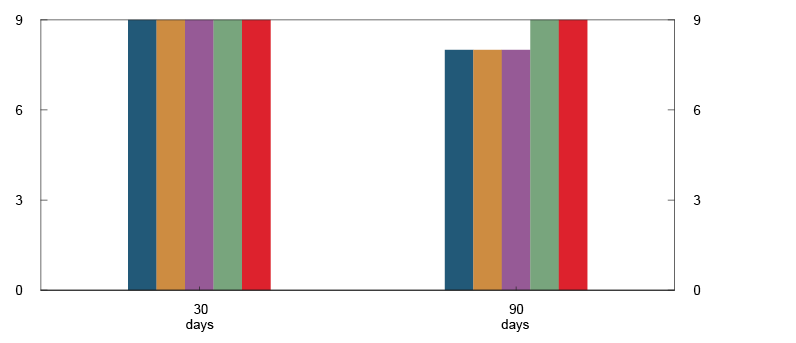

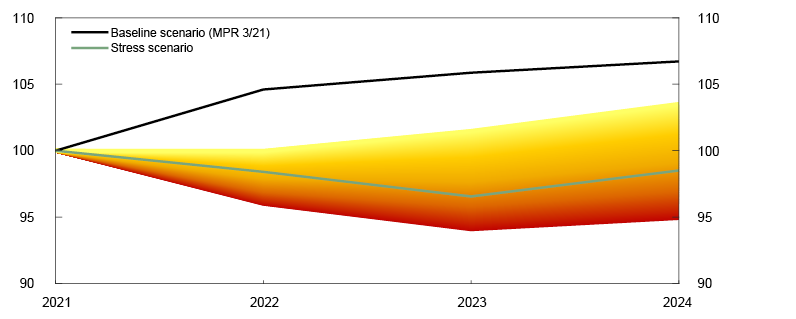

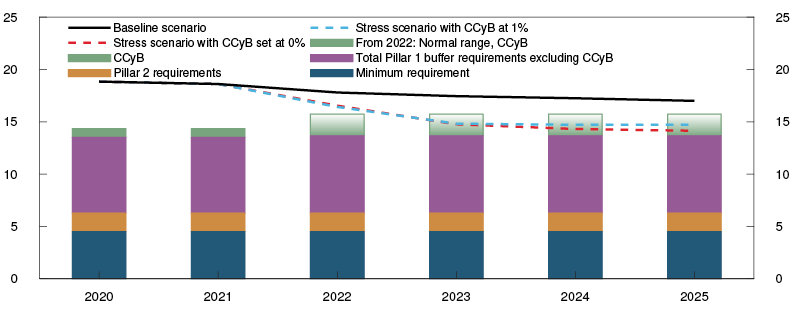

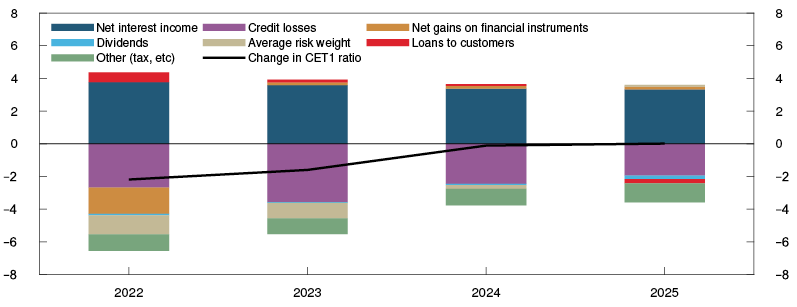

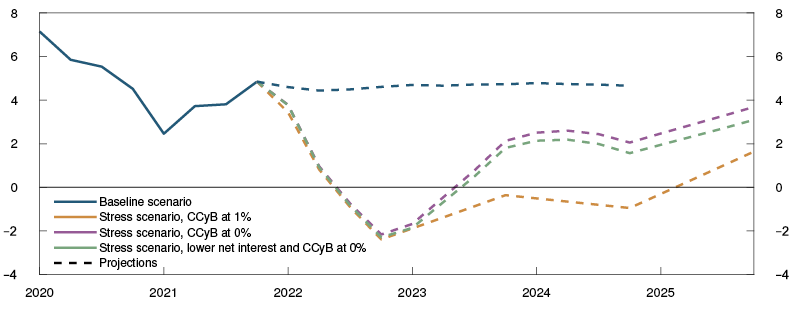

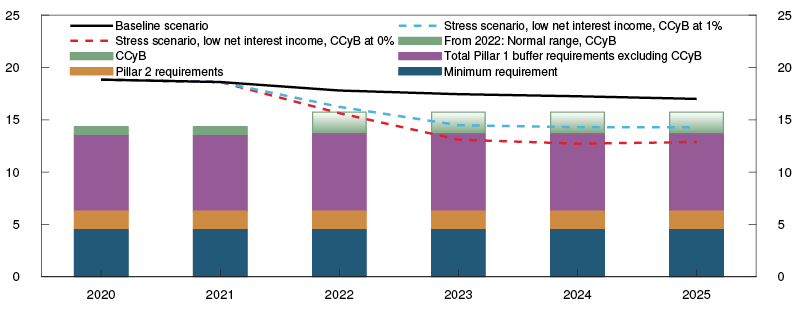

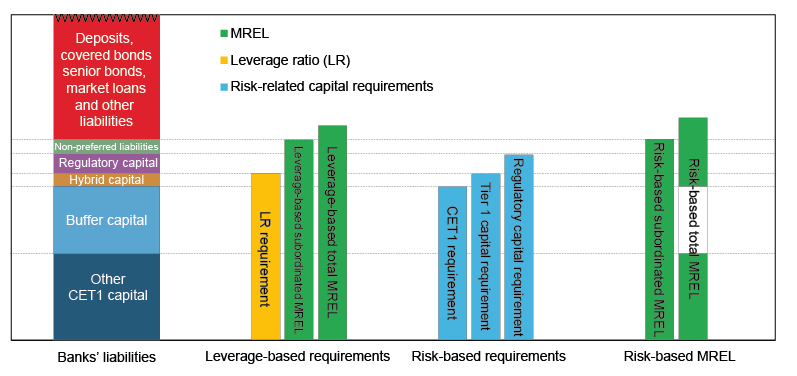

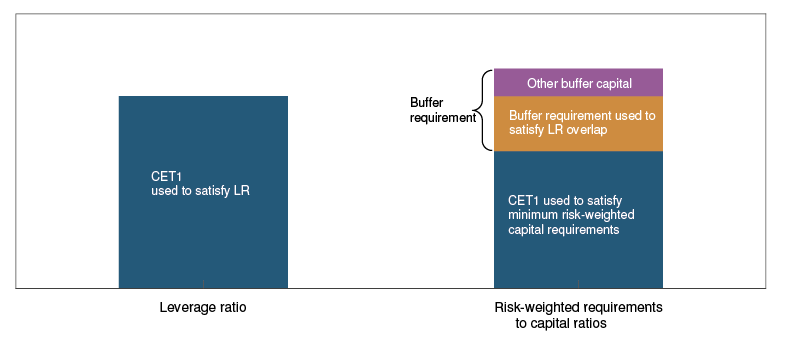

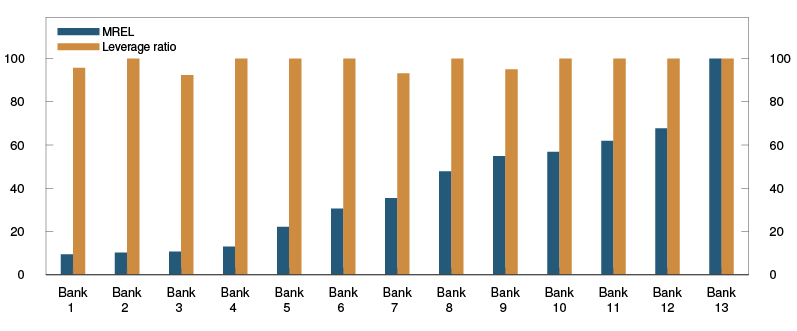

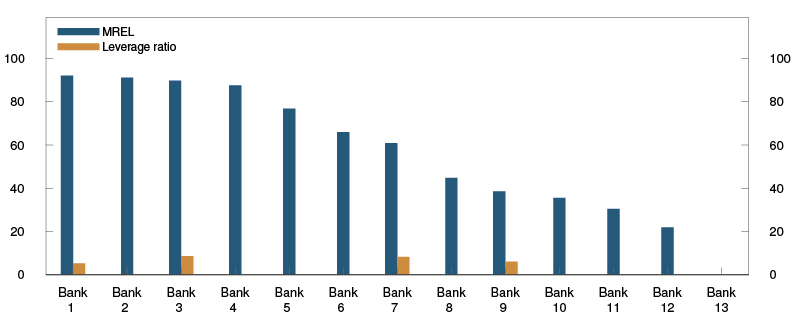

It is difficult to identify and assess the risk of new shocks, of which the pandemic is an example. The stress test in this Report shows that if the Norwegian economy is hit by a renewed sharp downturn, the capital buffers in the largest Norwegian banks as a whole are sufficient to absorb the losses. The implications for banks’ capital situation depends on which industries are affected. The stress test shows that weak developments in commercial real estate and other sector-specific shocks can induce banks to tighten lending, which can amplify an economic downturn. Banks can dip into their capital buffers to avoid tightening lending. Banks can also use freed-up capital if the countercyclical capital buffer rate is lowered. Analyses show that a number of Norwegian banks will have limited scope to dip into other capital buffers, such as the systemic risk buffer, without breaching the minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL). This may reduce the effectiveness of the buffers in a crisis. Banks preferring to maintain the flexibility that capital buffers provide can issue enough non-preferred senior bonds so that MREL does not hinder the use of capital buffers. If the buffer requirements are reduced in a sharp downturn, the most binding MREL requirement will be reduced accordingly and the buffers will be able to function as intended.

Liquidity measures and market stress

Extraordinary loans to banks during the market stress in spring 2020 ensured banking sector liquidity and the transmission of the policy rate to money market rates. At the same time, there was an increased need for liquidity by investment funds and other asset managers when the value of their securities fell and the krone depreciated. Fire sales to meet this need amplified the market stress. There is a discussion internationally and in Norway about whether central banks should have instruments that can be aimed directly at securities markets and non-bank market participants in periods of market stress.

Norges Bank’s liquidity policy instruments are aimed directly at banks. Banks create and receive deposits and thus play a key role in payment and credit intermediation. This is the reason they are Norges Bank’s counterparties and receive liquidity support if Norges Bank deems it necessary. Norges Bank’s risk is contained by the fact that banks’ liquidity and credit risk is strictly regulated, loans are extended against collateral and the terms and conditions for support are intended to give banks incentives to use market solutions first.

Instruments aimed directly at securities markets or non-bank market participants may entail a greater risk to the central bank. Asset purchases entail a higher risk than secured lending. Other market participants may face less strict regulation than banks, and their importance for payment and credit intermediation may be less critical. Loans to these counterparties may thus increase the central bank’s risk and can to a lesser extent be justified on the grounds that they are critical to the financial system. Such use of instruments also increases the risk that the central bank contributes to socialisation of potential losses, while the risk taker keeps any gains. This could give rise to excessive risk-taking and market adjustments that are detrimental to long-term financial stability. The central bank should therefore be cautious in resorting to such extraordinary measures. In line with the principle that risk should be borne as much as possible by financial market participants, loans to banks are Norges Bank’s preferred instrument in periods of market stress.

Resilient market participants must always be the first line of defence against market stress. Banks and other financial market participants are responsible for managing their own liquidity risk and cannot rely on support from the central bank. Strict criteria and terms and conditions for central bank measures are meant to help ensure this. Systemic risk connected with derivatives contracts, which played out at the beginning of the pandemic, have prompted a number of asset managers to make changes to their risk management. These changes may make them better positioned in periods of market stress.

The Norwegian financial system is vulnerable to cyber attacks

Cyber attacks are a potential threat to financial stability. Extensive digitalisation and interconnectedness make the financial system vulnerable. Financial institutions report more and increasingly sophisticated attacks. A more aggressive threat landscape is amplifying cyber risk.

The potentially systemic ramifications of cyber attacks entail a need for strengthened regulation and expanded collaboration between various authorities and financial system participants. A number of new regulatory initiatives have been proposed to increase financial sector cyber resilience. In September, Norges Bank’s Executive Board approved the introduction of a framework for testing entities’ capabilities in detecting and responding to cyber attacks (TIBER-NO). TIBER-NO has been prepared in collaboration with Finanstilsynet (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway). This will help strengthen financial sector cyber resilience and provide additional knowledge about how cyber attacks can impact the financial system.

Identifying key financial and operational dependencies in the financial system known as cyber mapping, is useful for ascertaining how cyber attacks can threaten financial stability. This is also a prerequisite for system-wide monitoring of cyber risks and proper incident management in the event of a cyber attack. In Norway, such cyber mapping work is underway in view of the new Security Act. This work is laying an important foundation for greater understanding of and new measures to address systemic cyber risk in Norway.

Other societal trends have implications for financial stability

The financial system is evolving in pace with technological innovation. Norway is at the technological forefront, and the payment methods we use have undergone extensive changes in recent years. An efficient and secure payment system is essential to financial stability. Norges Bank is studying whether the introduction of a central bank digital currency (CBDC) will promote an efficient and secure payment system and safeguard confidence in the payment system. In the coming two years, Norges Bank will conduct experimental testing of technical solutions.

In recent years, the prevalence and market capitalisation of crypto-assets have increased substantially. Crypto-assets are not considered a threat to financial stability yet, either globally or in Norway, but this can change in the future. A number of international regulatory initiatives can help ensure that developments do not pose a threat to financial stability. Central banks and other authorities should monitor developments and assess whether further regulations are needed that can reduce risks associated with crypto-assets.

Climate change and the climate transition affect all segments of society, also the financial system. The longer one waits to implement measures to make the necessary adaptations, the faster substantial changes will have to be made. Adapting suddenly and quickly may entail a risk to financial stability. The transition to lower greenhouse gas emissions and new regulations entail a transition risk for the Norwegian economy in the coming years, which is amplified by the importance of the oil and gas industry for Norway. Climate risk also relates to the physical consequences of climate change. Banks should ensure that they are well equipped to manage climate risk. The analyses in this Report show that Norwegian banks’ direct exposure to higher prices for greenhouse gas emissions is moderate. For now, Norwegian banks’ exposure to “known” physical climate risks is small, but the ramifications of climate change may be far more extensive than currently assumed.

Within their mandates, central banks and financial supervisory authorities can promote financial stability by ensuring that all risks are backed by sufficient capital and by encouraging the financial sector to include and communicate climate risk in their risk assessments and financial reporting. The ability of banks and other financial institutions to price climate risk correctly is crucial for the ability of borrowers to make good investment decisions. A sound information basis and transparency regarding exposures to climate risk also provide a solid basis for market participants to compare banks. Reporting standards are under development internationally. It is important to continue to develop climate reporting to obtain the most accurate picture of the climate risks facing Norwegian banks.

Øystein Olsen

Ida Wolden Bache

Øystein Børsum

Ingvild Almås

Jeanette Fjære-Lindkjenn

3 November 2021

1 Financial system vulnerabilities and risks

Vulnerabilities in the financial system can have more serious consequences for financial stability in the face of shocks. The uncertainty surrounding the pandemic has abated, but high global risk appetite has driven up asset prices. The most important structural vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system are high household debt, high bank exposures to commercial real estate and the close interconnectedness of banks. Overall cyclical vulnerabilities are at pre-pandemic levels, but clearly lower than in the years preceding the financial crisis. House prices in particular have risen through the pandemic, and low yields have resulted in higher prices for commercial property and financial assets. Measures such as requirements for bank capital, liquidity and credit standards have addressed these vulnerabilities, increasing the resilience of the financial system.

1.1 Risk of shocks

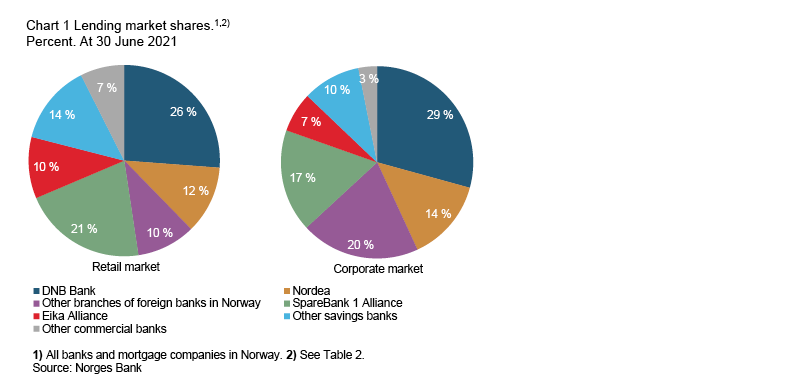

Shocks that can threaten financial stability can come from different parts of the economy and financial markets. Such shocks may be difficult to foresee. Shocks often spread to Norway from abroad since the financial system largely operates across borders. Cross-border integration is particularly close in securities markets. Large Norwegian banks obtain substantial funding abroad, and foreign banks account for over a quarter of loans in Norway. This integration provides opportunities for diversification of risk, but also enables contagion from global turbulence and uncertainty to the Norwegian financial system.

The Covid pandemic is an example of a shock that was difficult to foresee, but that had considerable consequences for the real economy and immediately led to substantial financial market stress. Extensive government measures stabilised markets quickly and later limited the pandemic’s impact on banks and their customers. This helped banks to weather the pandemic well. There has been little turbulence in global financial markets this past year, and the Norwegian economy has recovered. Uncertainty about the pandemic is lower than at the time of Financial Stability Report 2020.

High global risk appetite

Prior to the pandemic, global financial markets were characterised by low yields and high risk appetite. This pushed down risk premiums and pushed up prices for assets, such as property and equities. The pandemic triggered a sharp downturn and heightened fears about the future, which partly reversed these trends. Extensive government measures, including an expansionary monetary policy, eased financial conditions. Considerable progress in fighting the pandemic has also contributed to the economic recovery.

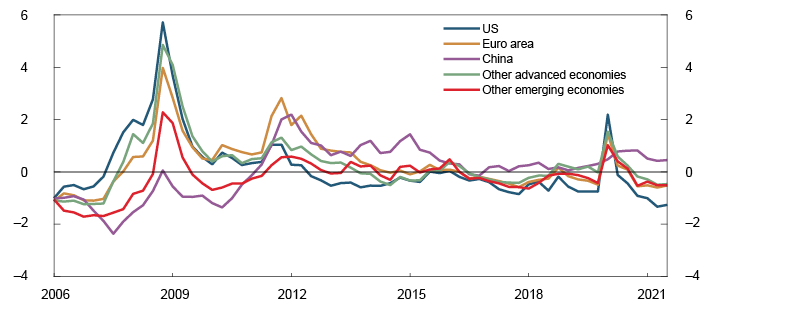

Risk appetite is high again. According to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) aggregate index, financial conditions in most advanced economies are now as they were prior to the pandemic (Chart 1.1). In the US, similar financial conditions have not been seen since before the financial crisis. Developments especially reflect lower interest rates, higher equity prices and higher house prices. High merger and acquisition activity, a growing number of initial public offerings and increased high-yield debt issuance also indicate high risk appetite.

Chart 1.1 Greater stimulus from financial conditions over the past year1 IMF’s aggregate financial condition index. Standard deviation from the mean

This autumn, global equity prices have varied more, and long-term interest rates have edged up. At the same time, global economic growth has slowed somewhat, and the outlook is more uncertain. This may reflect bottlenecks in global and domestic distribution chains on the back of the rapid recovery after the pandemic. The bottlenecks and higher energy prices have pushed up inflation. Policy rate expectations have risen in a number of countries, and some central banks have raised their policy rates. This may be favourable for financial stability in that it restrains debt accumulation and the rise in asset prices.

Sudden shifts in inflation or interest rate expectations can reduce risk appetite substantially and lead to higher riskpremiums and repricing in global financial markets, with a related decline in asset prices and higher financing costs and contagion to the Norwegian financial system.

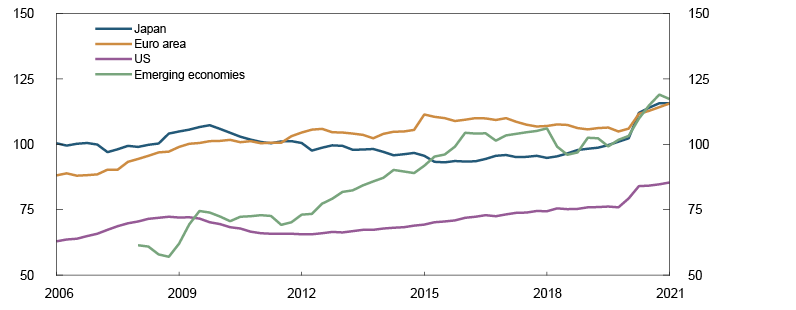

High indebtedness increases the risk of financial stability in the event of a sudden and pronounced tightening of financial conditions. Global non-financial sector debt now accounts for around 250% of GDP, up from around 180% prior to the financial crisis in 2008. This means that vulnerabilities to an interest rate increase are historically high. Both public and private debt-to-GDP ratios have risen sharply through the pandemic. Some of this reflects the fall in GDP. In the private sector, the increase in debt is strongest for non-financial corporates, where debt-to-GDP ratios are also clearly higher than prior to the financial crisis (Chart 1.2). However, advanced economies’ total household debt is lower than it was prior to the global financial crisis.

Chart 1.2 Corporate debt has risen in many countries2 Non-financial corporate debt as a share of GDP. Percent

Growing complexity due to more market-based financing and increasing role of non-banks

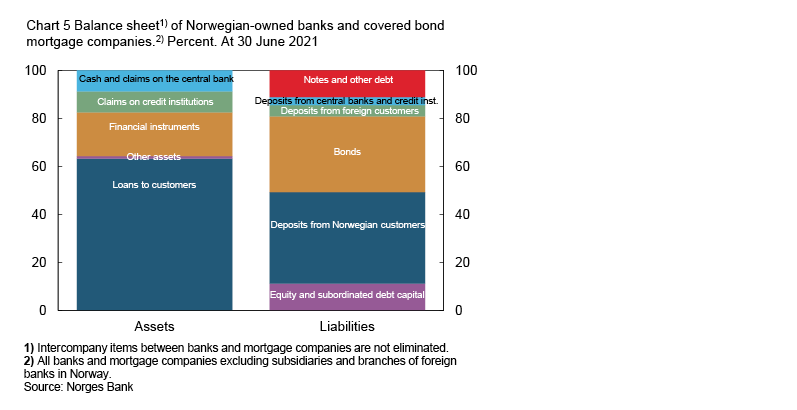

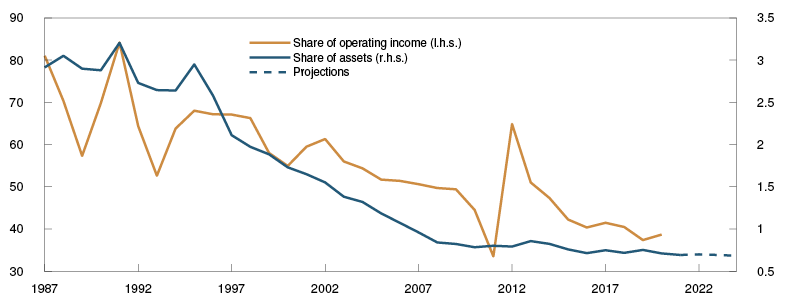

Globally, firms’ market-based financing has increased over the past 10 years, and this continued during the pandemic. The market share of non-bank financial institutions has increased. Globally, there is now more capital under management by such entities than by banks (Chart 1.3). Growth in various types of investment funds has been particularly strong.

Chart 1.3 Banks losing market share globally3 Composition of the global financial sector. Capital under management in trillions of USD

Increased market financing and a greater role for non-banks provide better opportunities for spreading risk between the banking sector and other financial system participants. This may reduce concentration risk but at the same time expose the system to other risks and new contagion channels in the event of market stress. The financial system may become more complex, which can result in other kinds of financial crises that call for different sorts of measures than previously.

Following the financial crisis in 2008, bank liquidity and solvency were strengthened owing to new international regulation. This made the banking sector more resilient to shocks and helped ensure that it largely functioned well during the pandemic. Stricter banking regulation also contributed to migration of risk to the less heavily regulated non-bank sector, likely for profitability reasons. The turbulence in spring 2020 revealed weaknesses in this portion of the global financial system. Therefore, an extensive worldwide effort is now underway to increase resilience in the non-bank sector.4

In Norway, the market turbulence in spring 2020 presented challenges to investment managers and also spread further to other parts of the financial system. Large movements in prices for financial assets and the sharp krone depreciation led to high margin calls for Norwegian asset managers.5 This subjected many managers to liquidity squeezes and also adversely affected other participants by pushing up bond market risk premiums. A number of Norwegian asset managers have made changes to their risk management, including greater use of repurchase agreements and increased collateral eligibility of bonds. These changes may make them better positioned in the event of renewed market stress and mitigate the risk of shocks spreading to the rest of the financial system.

1 Period: 2006 Q1 – 2021 Q3.

2 Period: 2006 Q1 – 2021 Q1. Data for emerging economies from 2008 Q1.

3 Period: 2006 – 2019. Non-bank financial institutions includes eg pension and insurance vehicles and various funds.

4 This is primarily under the auspices of the Financial Stability Board (FSB) (see FSB (2021) “Lessons Learnt from the COVID-19 Pandemic from a Financial Stability Perspective. Final Report”. October 2021.

5 See Financial Stability Report 2020, page 20 and Alstadheim, R., K.B. Nordal, O. Syrstad, S. Ter Ellen and M.-I. Walstad Wassås (2021) ”Bond market fire sales and turbulence in the Norwegian FX market in March 2020”. Staff Memo 2/2021. Norges Bank.

1.2 Structural vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system

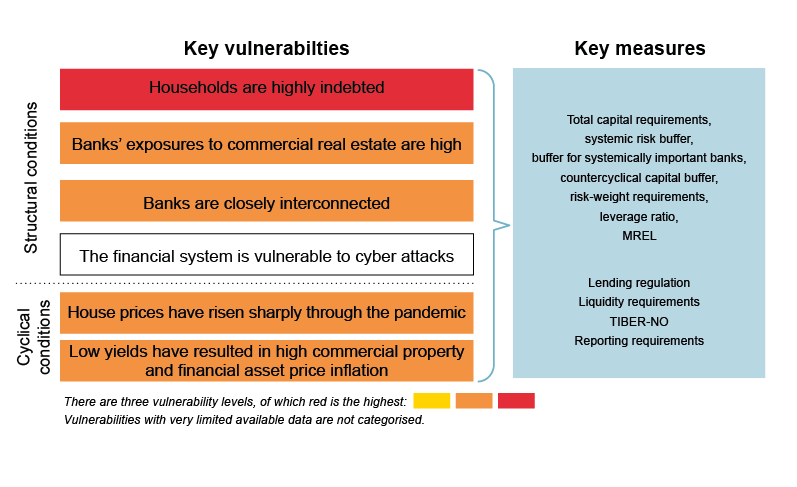

Owing to vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system, negative shocks can have more severe consequences for financial stability. In the assessment of vulnerabilities, we distinguish between cyclical vulnerabilities, which typically vary over time (see Section 1.3), and vulnerabilities of a more structural nature (see "Financial system vulnerabilities in Norway and measures implemented"). The main structural vulnerabilities are high household debt, banks’ large commercial real estate exposures and bank interconnectedness. Extensive digitalisation also entails a vulnerability to cyber attacks (see Section 1.4).

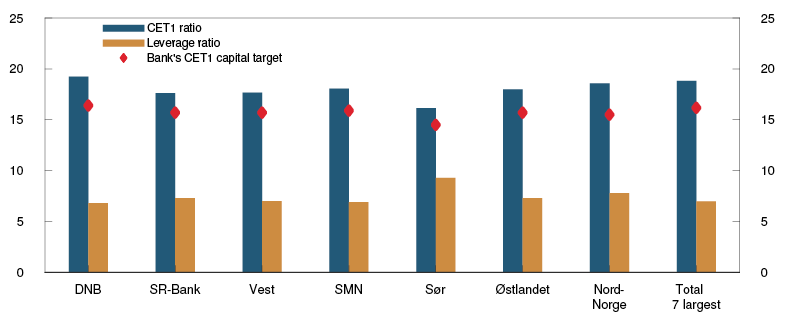

A number of measures have addressed structural vulnerabilities. Several of these measures affect banks’ total capital requirements, such as requirements for the systemic risk buffer, risk-weighting and the leverage ratio, and a minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL). There are also requirements for banks’ liquidity and credit standards. The level of the systemic risk buffer was raised from 3% to 4.5% with effect from end-2020.6 Norges Bank supported the increase in the buffer level.7 This autumn, Norges Bank was given formal advisory responsibility for the systemic risk buffer and will develop a framework for providing advice on the buffer rate in 2022.

Financial system vulnerabilities in Norway and measures implemented

Vulnerabilities are identified to assess whether sufficient measures have been implemented. Since the financial crisis in 2008, the Norwegian authorities have introduced a number of rules to mitigate vulnerabilities and increase financial system resilience (see diagram above). For more detailed information about the measures, see "Important measures to mitigate financial system vulnerabilities in Norway".

The measures primarily help to increase financial system resilience, but can also mitigate vulnerabilities. Many of the measures contribute generally to increased resilience, and measures are often justified on the basis of a number of vulnerabilities, both those mentioned in the diagram and other financial system vulnerabilities. The countercyclical capital buffer is the only measure purely justified on the basis of cyclical vulnerabilities. High bank profitability and a robust bank funding structure also strengthen resilience (see Section 2).

Vulnerabilities will still exist even after a large number of measures are introduced. However, systemic risk is assessed after taking into account these measures and the resilience of the financial system and the wider economy. If necessary, Norges Bank will implement or advise the adoption of measures.

Households are highly indebted

High household debt has long been the main structural vulnerability in the Norwegian financial system. Household leverage is high both historically and compared with other countries. High household debt in Norway partly reflects elevated house prices and a large proportion of home ownership. High indebtedness makes households vulnerable to a loss of income, a rise in lending rates or a fall in house prices. The risk that many households tighten consumption at the same time represents a threat to financial stability. Such a tightening may amplify an economic downturn. This can reduce firms’ earnings and debt-servicing capacity, leading to increased losses on banks’ corporate exposures.

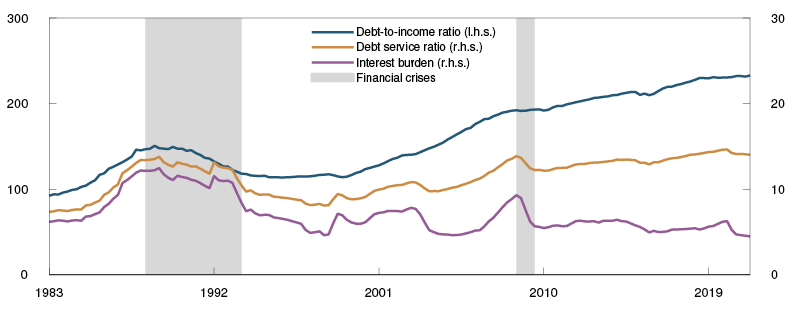

In recent years, debt growth has slowed somewhat but continues to rise a little faster than income, pushing up household leverage (Chart 1.4). Owing to low interest rates, households’ interest burden, ie the share of income spent on interest payments on loans, is low from a historical perspective, despite high household leverage. This is because nearly all debt is floating rate. Overall debt service ratios, which include both interest and estimated principal, are high and are expected to rise from 14.0% in 2021 Q2 to 15.3% at end-2024, primarily owing to higher lending rates (see Monetary Policy Report 3/21).

Chart 1.4 Household leverage is high and edging higher8 Percent

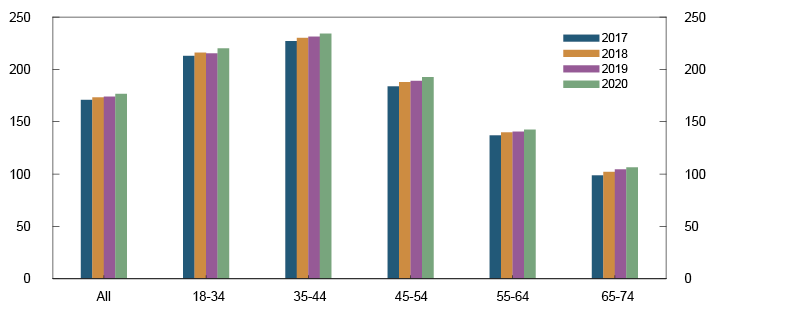

Data from pre-completed tax returns9 for 2020 make it possible to see the breakdown of debt across different groups and show that debt-to-(gross) income ratios increased for all age groups in 2020 (Chart 1.5). This reflects sustained debt growth through the pandemic, while income growth slowed. Among younger groups, average debt-to-income ratios fell in 2019, largely owing to relatively high income growth, though debt ratios picked up again in 2020.

Chart 1.5 Higher leverage in all age groups in 2020 Debt as a share of gross income. Percent

Even though household debt is rising somewhat faster than income, wealth has increased owing to high house price inflation and high household saving through the pandemic. Increased saving reflects limited consumption opportunities and greater uncertainty about the future. Much of the increased saving took the form of bank deposits, which are liquid and stable assets. Data from pre-completed tax returns show that the increase in bank deposits has been broad-based in the population.10 Both those with high and with low debt-to-income ratios increased their bank deposits substantially in 2020. The data also show that household financial assets excluding bank deposits increased in all age groups in 2020.

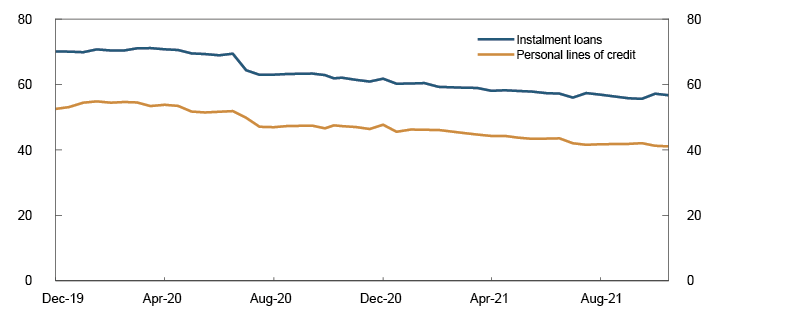

Unsecured debt, such as consumer credit, grew sharply over many years and accounts for around 3% of household debt. After the introduction of the consumer credit regulation in 2019 and the establishment of credit registers, the volume of consumer credit fell. The fall continued through the pandemic (Chart 1.6). There are substantially fewer borrowers with very high consumer debt than previously.

Chart 1.6 Consumer debt is falling11 Unsecured interest-bearing debt with an interest rate above 8 percent. In billions of NOK

Measures by the authorities to limit borrowing, such as regulation of banks’ credit standards, have contributed to more moderate growth in total household debt since 2017. Requirements for banks’ credit standards limit in particular excessive borrowing by vulnerable households. The requirements are in force until 2024, but are to be evaluated in 2022. Moreover, banks’ requirement to hold a systemic risk buffer is warranted in part by the high level of household debt.

Older persons account for a growing share of the population. The pension reform has given people greater responsibility for their own pensions and how their pensions will be drawn. Life expectancy has also risen, which means having to stay on at work longer to receive the same pension as before. Individuals are also more exposed to return risk on their pension assets. Many older persons may experience a substantial fall in income after the transition from wage income to a pension in the years ahead. Combined with rising leverage, this can make older persons more vulnerable to higher interest rates or a fall in house prices, for example, or if they cannot remain at work as long as they like.12 Our assessment is that these trends overall do not represent a material threat to the financial system. Among other reasons, this is because older persons generally have solid finances and the most at-risk groups hold a relatively small share of household debt. Moreover, the financial sector and future pensioners have time to adjust to the changes.

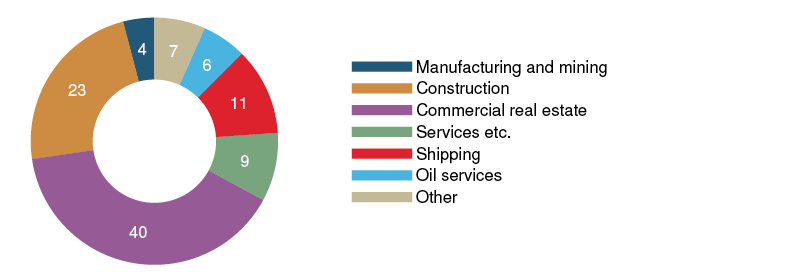

Banks’ exposures to commercial real estate are high

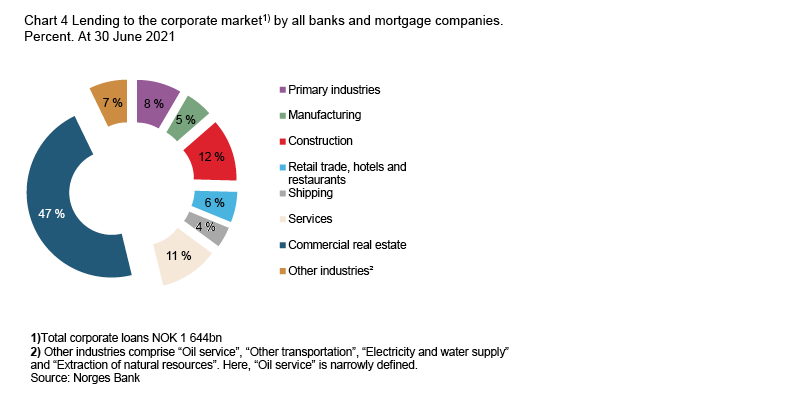

Another key structural vulnerability is banks’ high commercial real estate exposures, which reflect in part high commercial property prices. CRE exposures account for around half of total corporate lending (Annex Chart 4), and all large banks’ CRE exposures are high. Experience from Norway and other countries shows that losses in this sector can be substantial in sharp downturns.

CRE firms are more leveraged than other firms, making them vulnerable to interest rate increases or a fall in rental income. A majority of the banks in Norges Bank’s lending survey reported that the ordinary maturity of new commercial property mortgages over the past six months was under five years, little changed compared with prior to the pandemic. Short maturities expose CRE firms to refinancing risk. Rapid price rises in recent years (Chart 1.11) have not been matched by corresponding borrowing by CRE firms. This has boosted these firms’ equity ratios, making them better equipped for a price fall. In the lending survey, most banks report ordinary loan-to-value (LTV) ratios of between 60% and 80%. LTV ratios are little changed from pre-pandemic levels.

CRE firms’ income is assured in the short term by existing leases, as long as the tenants are able to pay rent. In the event of higher commercial property vacancy rates and a fall in rental prices, CRE firms’ income may gradually weaken as existing leases expire. In that case, loan defaults may increase, and banks may incur losses if the properties’ mortgage value is lower than the value of the loans. A marked fall in commercial property prices in a stress situation can lead to substantial bank losses, as shown in the stress test in Section 3. The level of the systemic risk buffer is warranted in part by banks’ substantial CRE exposures. In addition, minimum requirements for risk weights on CRE exposures have been introduced.

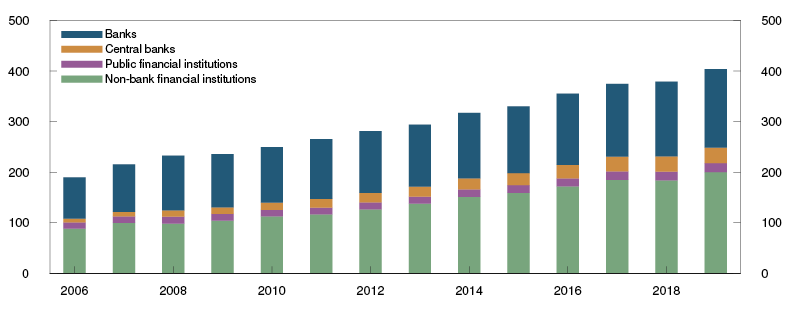

Banks are closely interconnected

Banks are directly interconnected through interbank exposures and indirectly through common or similar securities portfolios among other things. Close interconnectedness represents a key financial system vulnerability because shocks spread more easily. Nevertheless, a high level of interbank cooperation in the fixed income market is crucial for ensuring the distribution of liquidity and the effective transmission of monetary policy.

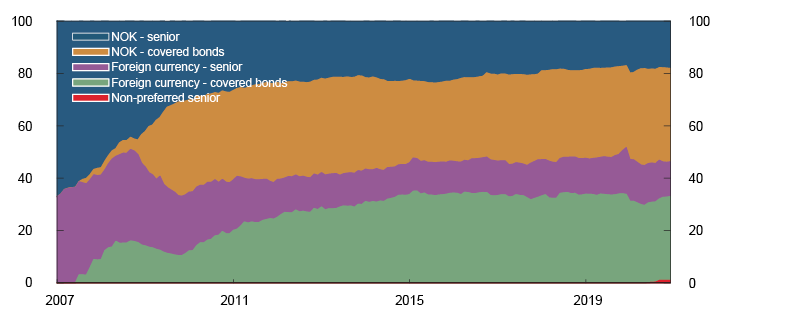

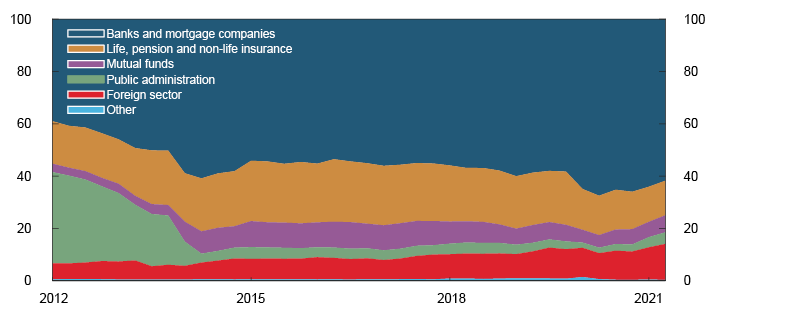

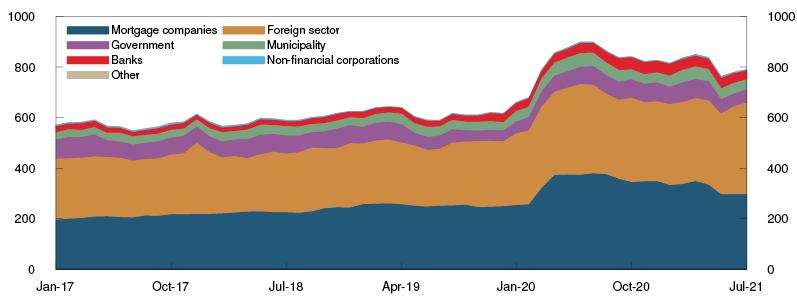

Bank interconnectedness through the covered bond market represents a particular vulnerability. Covered bonds account for two-thirds of banks’ wholesale funding, while banks own approximately 60% of covered bonds issued in NOK (Charts 1.7 and 1.8), which means they act both as issuers and investors in this market. Banks mainly hold covered bonds as part of their liquidity portfolios (see Section 2). The high ownership share reflects the view that covered bonds are safe securities that are used to satisfy liquidity requirements and as collateral for loans from Norges Bank. Banks’ share of covered bond holdings rose after the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) was introduced in 2014.

Chart 1.7 Banks’ covered bond funding is substantial13 Breakdown of bond funding outstanding. Percent

Chart 1.8 Banks’ hold the majority of covered bonds in NOK14 Ownership breakdown of bonds issued by Norwegian mortgage companies in NOK. Percent

The purpose of the liquidity portfolio is to enable banks to sell or pledge securities if they have difficulty obtaining new funding. Simultaneous fire sales of covered bonds by a large number of banks can drive down the prices for these securities and thus the value of the liquidity portfolios. This can aggravate banks’ liquidity situation and make it difficult for them to raise new covered bond funding. A concurrent fall in house prices can further exacerbate funding problems and amplify the sell-off of both covered bonds and other securities banks hold to address liquidity problems.

Earlier analyses have shown that fire sales of securities can result in contagion effects that can lead to losses in the Norwegian banking sector.15 The losses are primarily due to the potential for a bank’s fire sales of securities to drive down prices for both the securities being sold and other similar securities. Other banks holding these securities then need to reduce the carrying amount to the new and lower price. The systemic risk buffer requirement is warranted in part by the ramifications of a closely interconnected financial system.

6 The increase effective from end-2020 applied to IRB banks, but for other banks, the increase applies from end-2022.

7 See Norges Bank’s høringsuttalelse om tilpasninger til kapitalkravene for banker [consultation statement on adjustments to banks’ capital requirements]. 30 September 2019 (in Norwegian only).

8 Period: 1983 Q1 – 2021 Q2. Debt-to-income ratio is loan debt as a percentage of disposable income. Disposable income is income after taxes and interest payments. Debt service ratio is interest and estimated principal payments as a percentage of after-tax income. Interest burden is interest payments as a percentage of after-tax income.

9 Ie the forms individual taxpayers receive for review in April each year.

10 See box on page 60 of Monetary Policy Report 3/21.

11 Period: 1 December 2019 – 16 October 2021.

12 See Reiakvam, L., H. Solheim and B.H. Vatne (2021) “De eldre har i dag en sterk finansiell stilling, men gjeldsgraden øker” [Older persons currently enjoy a strong financial position, but their leverage is increasing]. Blog post published on the Bankplassen blogg, 12 October 2021. Norges Bank (in Norwegian only).

13 Period: January 2007 – December 2020.

14 Period: January 2007 – December 2020.

15 See box on page 45 of Financial Stability Report 2019.

1.3 Cyclical vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system

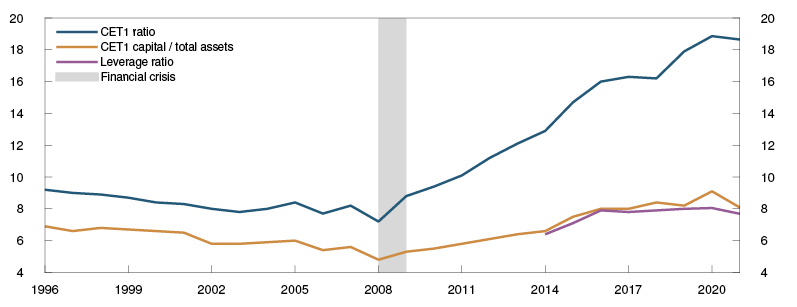

Debt growth and asset price inflation have often been high prior to financial crises and are therefore indicators of cyclical vulnerabilities. Overall, cyclical vulnerabilities are assessed as little changed compared with before the pandemic. A broad set of indicators of cyclical vulnerabilities is now at a medium level from a historical perspective, while the indicators signalled high cyclical vulnerabilities prior to the financial crisis (see "A broad set of indicators indicates medium cyclical vulnerabilities"). The indicators in the analysis include changes in credit, house prices, commercial property prices and equity prices.

Banks should build and hold a countercyclical capital buffer when cyclical vulnerabilities are building up or have built up. In the event of a sharp downturn and markedly reduced access to credit, the countercyclical capital buffer rate can be reduced to increase banks’ lending capacity. In March 2020, the buffer rate was reduced from 2.5% to 1% to prevent tighter bank credit from amplifying the downturn. In June 2021, it was decided to increase the countercyclical capital buffer rate to 1.5% from 30 June 2022. In September, Norges Bank announced that based on its assessment of economic developments and the prospects for bank losses and lending capacity, the buffer rate will be raised to 2.0% in December, effective from 31 December 2022. Norges Bank has further stated that it expects the buffer rate to return to 2.5% somewhat further out.

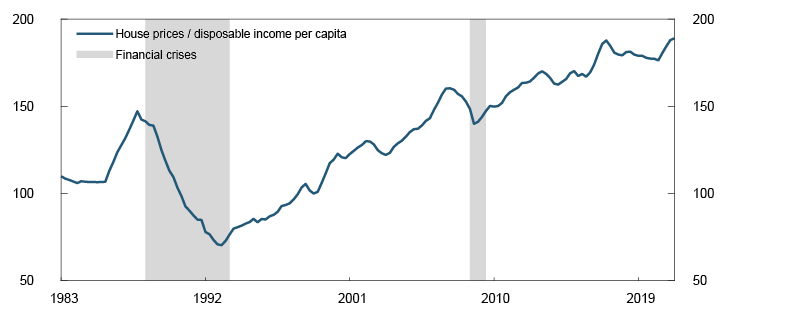

House prices have risen sharply through the pandemic

High house price inflation over time increases the risk of price falls that can lead to a tightening of household consumption and thus to bank losses. Moreover, a sharp fall in house prices can create shocks to banks’ liquidity and covered bond funding.

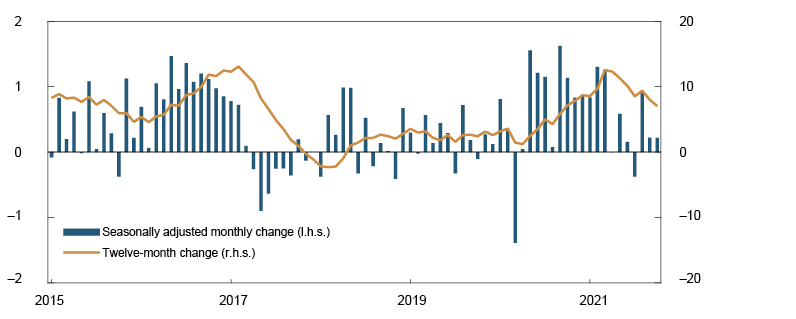

After several years of rapid house price inflation, where prices rose faster than household income, house price inflation over the few years prior to the coronavirus outbreak was at a moderate level (Chart 1.9). At the start of the pandemic, house prices fell (Chart 1.10). However, house prices rose markedly through summer 2020, and the rise in prices was high in the period to spring 2021. The rapid rise reflects low residential mortgage rates and homebuyers’ preference for using a greater share of income on housing, among other reasons because remote working has increased and consumption opportunities have otherwise been limited. Growth in household debt accelerated through the pandemic owing to rapid house price inflation, but has now levelled off.

Chart 1.9 House prices have risen faster than income through the pandemic16 Index. 1998 Q4 = 100

Chart 1.10 House price inflation has been moderate over the past half-year17 House prices. Percent

House price inflation has been more moderate in recent months. Moderate house price inflation is expected ahead (see Monetary Policy Report 3/21). This reflects higher lending rates, normalising household consumption patterns and an increase in residential construction.

Low yields have resulted in high commercial property price and financial asset inflation

Prices for commercial property and a number of financial assets, such as equities and bonds, have risen considerably through the pandemic. The swift rise reflects factors such as historically low interest rates, with low yields in a number of markets. This is an important global trend (see Section 1.1), but it also applies to Norway.

In the CRE sector, the office market is particularly important for financial stability since banks’ exposures to this segment are substantial. A large share of the stock of office buildings is located in Oslo, and prices for prime office space in Oslo is one of many indicators of cyclical vulnerabilities (see "A broad set of indicators indicates medium cyclical vulnerabilities").

Commercial property prices, measured as selling prices for prime office space in Oslo, have risen considerably in the years after the financial crisis (Chart 1.11). Selling prices fell somewhat at the start of the pandemic, but the fall was quickly reversed and prices continued to rise. Prices have levelled off during autumn. Selling prices are calculated as rents divided by yield.

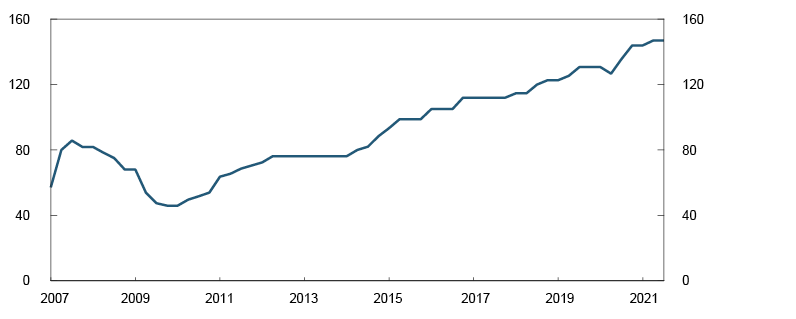

Chart 1.11 Commercial property prices have risen considerably18 Estimated selling prices for prime office space in Oslo. In thousands of NOK per square metre

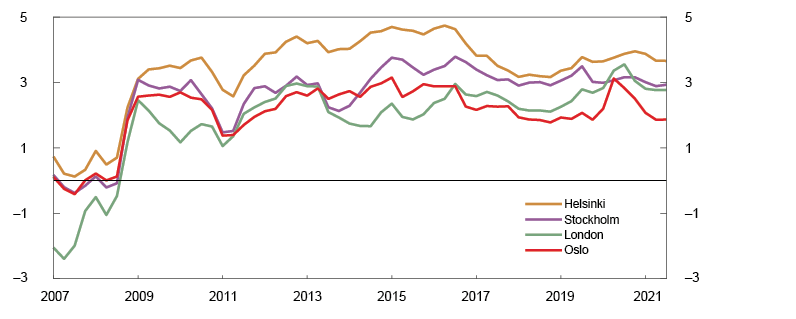

Lower yields in particular have pushed up commercial property prices through the pandemic. This largely reflects lower interest rates. The risk premium, measured as the difference between the yield and the five-year swap rate, rose during the pandemic, but is now close to its pre-pandemic level (Chart 1.12). The risk premium in Oslo is low compared with other European cities. Since the yield is at a low level, prices are sensitive to increases in risk premiums or long-term interest rates. A sharp fall in commercial property prices can lead to large bank losses (see Section 3). However, moderate commercial property price inflation is expected in the coming years (see Monetary Policy Report 3/21).

Chart 1.12 Risk premium in Oslo is low19 Yield less five-year swap rate. Percentage points

Rental prices fell weakly at the start of the pandemic but are now back to around their pre-pandemic level. Norges Bank has recently changed its provider of price statistics (see"New provider of commercial property price data"). The new data source is likely to give a more representative picture of developments in office rents in Oslo as a whole, since the new statistics include a broader set of office premises. The statistics show somewhat lower rents, and thus lower selling prices, than before. New price statistics and our recent access to microdata for most commercial buildings in Norway help to improve the basis for analyses of commercial property.20

New provider of commercial property price data

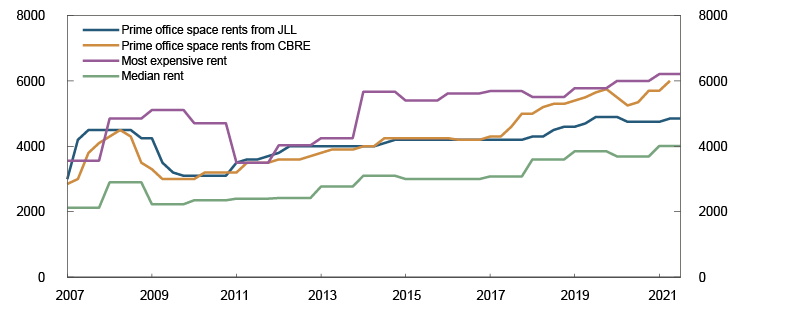

Norges Bank has recently changed provider of price statistics for prime office space from CBRE to Jones Lang LaSalle (JLL). The new statistics for prime office space in Oslo are based on a broader set of office premises. CBRE’s rents are closer to the most expensive leases for office space at Aker Brygge and Vika than JLL’s rents (Chart 1.A). The gap between the indexes widened considerably in 2017, when CBRE’s rents rose markedly. In this period, CBRE narrowed its definition of what is regarded to be prime office space, which has probably contributed to the wider gap. Differences in the providers’ information basis and assessments can also contribute to differences between the price indexes.

Chart 1.A New rental price index is more representative1 Annual office rents in Aker Brygge and Vika. NOK per square metre

JLL’s rents are probably more representative of developments in rental prices for the office segment as a whole. The rental price index from JLL shows broadly the same developments as the quality-adjusted rental price index for Oslo as a whole and for Aker Brygge and Vika.2

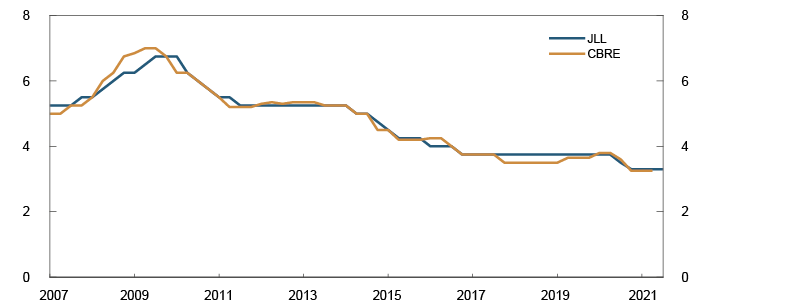

Commercial real estate selling prices are calculated as rental prices divided by yield. The yield in JLL’s and CBRE’s statistics is fairly similar (Chart 1.B). Lower rents lead to a lower level of selling prices with JLL’s data, but both sets of statistics show high overall selling price rises through the pandemic.

Chart 1.B The yield is fairly similar3 Yield for prime office space in Oslo. Percent

1 Period: 2007 Q1 – 2021 Q3. Data for the most expensive and median rents are at annual frequency.

2 Se Financial Stability Report 2019 for a comparison of the quality-adjusted rental price index with CBRE’s rental index.

3 Period: 2007 Q1 – 2021 Q3.

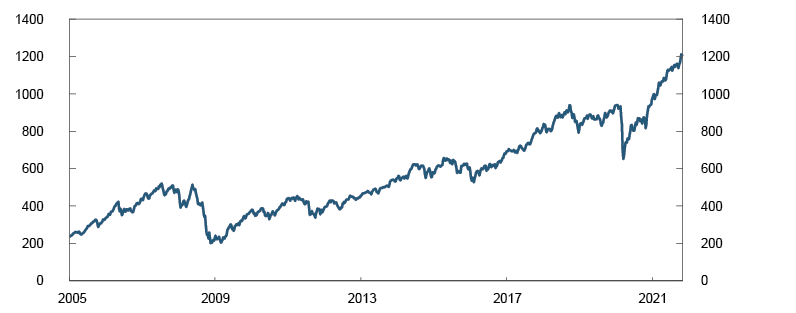

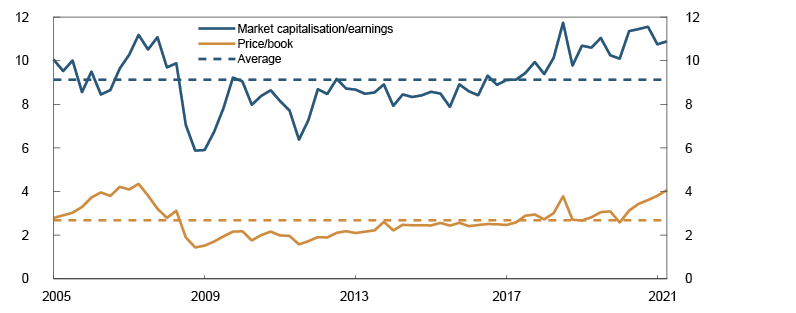

Lower yields and increased risk appetite have also fuelled high financial asset inflation. Equity prices have made strong advances through the pandemic (Chart 1.13). The Oslo Børs Benchmark Index has risen by 27% so far in 2021, and the index is now 32% higher than at the beginning of 2020. Price-to-earnings and price-to-book ratios for Norwegian listed equities now appear to be high, compared with averages for the past 15 years (Chart 1.14). In the corporate bond market, issuance volumes have been high so far in 2021, and risk premiums are close to pre-pandemic levels.

Chart 1.13 Equity prices have made strong advances21 Oslo Børs Benchmark Index

Chart 1.14 Equity valuations are high22 Market capitalisation-to-earnings and price-to-book ratios. Sample of Norwegian listed companies

A sharp fall in financial asset prices can threaten financial stability through a number of channels. Pension funds can incur large losses since portions of their benefit obligations are fixed. Banks’ liquidity portfolios, and thus banks’ liquidity, will also be impaired by a price fall. A substantial fall in financial asset prices can also adversely impact a number of other financial institutions, such as investment firms and insurance companies. In addition, many households own financial assets, even though their primary residence and other real estate account for most of household wealth. Households’ financial assets increased through the pandemic, which has bolstered households’ resilience. However, the increase in household financial assets increases the risk that a substantial fall in financial asset prices can lead to a tightening of consumption and bank losses, if firms default on their debt.

A broad set of indicators indicates medium cyclical vulnerabilities

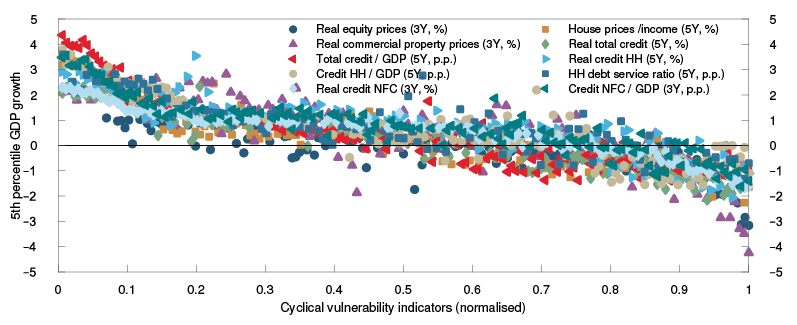

Empirical analyses show that financial crises hit harder when cyclical vulnerabilities are high prior to a crisis. With the aid of quantile regressions, we have linked the risk of sharp falls in GDP to measures of cyclical vulnerabilities.1

We use a broad set of cyclical vulnerability indicators. They include five-year changes in credit, house prices and household debt service ratio and three-year changes in commercial property prices and equity prices. Each indicator is normalised based on its historical distribution in the period, so that all indicators are scaled the same. Historical observations indicate that the estimated risk of a fall in GDP (vertical scale) rises with the level of cyclical vulnerabilities (horizontal scale) (Chart 1.C). Possible falls in GDP are measured at the 5th percentile, which means that five out of 100 cases of possible GDP growth are expected to be lower than this. The 5th percentile will be much lower than expected growth and provides a good starting point for quantifying possible crisis depth in stress tests (see Section 3).

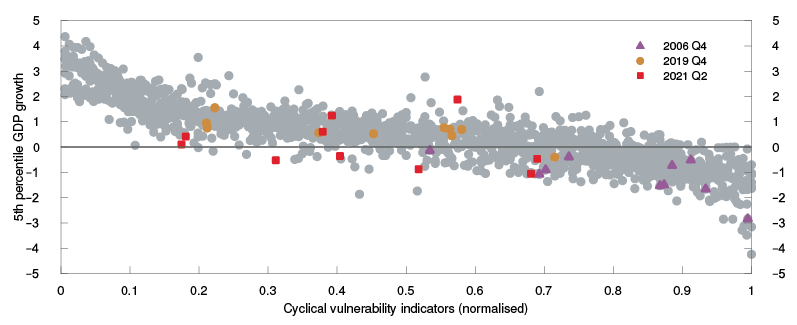

Chart 1.C Linkages between cyclical vulnerabilities and GDP growth2 Cyclical vulnerabilitiy indicators (normalised) on the horizontal scale and 5th percentile projections for GDP growth on the vertical scale

Overall, this analysis indicates that cyclical vulnerabilities are at a medium level relative to the indicators’ historical distribution. The vulnerability indicators are spread from low to high, but most lie at a medium level (Chart 1.D). Most indicators were also at a medium level prior to the coronavirus pandemic, while they were at high levels prior to the financial crisis. The two indicators showing the highest vulnerabilities for 2021 Q2 are growth in household and corporate credit as a share of GDP. High values for these two indicators largely reflect the fall in GDP through the pandemic, and the indicators will decline as GDP normalises. The projections in Monetary Policy Report 3/21 for credit, house prices, commercial property prices and GDP suggest that the indicators of cyclical vulnerabilities will edge down ahead.

Chart 1.D The analysis indicates a medium level of cyclical vulnerabilities3 Cyclical vulnerability indicators (normalised) on the horizontal scale and 5th percentile projections for GDP growth on the vertical scale

The analysis provides measures of cyclical vulnerabilities and appurtenant estimates of how far GDP can fall in the event of a sharp downturn (5th percentile). However, in the analysis, we do not have sufficient data to identify the importance of measures. Measures targeting banks, such as capital and liquidity requirements and risk management requirements, may help reduce vulnerabilities, but is the most important channel increasing banks’ resilience. This will better enable banks to absorb high credit losses and weak earnings without contributing to amplifying a downturn. Other requirements, eg mortgage requirements, can have a greater impact on household leverage and increase household resilience.

1 See Arbatli-Saxegaard, E.C., K.R. Gerdrup and R.M. Johansen (2020) “Financial imbalances and medium-term growth-at-risk in Norway”. Staff Memo 5/2020. Norges Bank.

2 Period: 1985 Q1 – 2021 Q2. HH stands for households and NFC stands for non-financial corporations. 3Y and 5Y stand for three- and five-year change, respectively.

3 Period: 1985 Q1 –2021 Q2.

16 Period: 1983 Q1 – 2021 Q2. Disposable income is income after taxes and interest payments.

17 Period: January 2015 – October 2021.

18 Period: 2007 Q1 – 2021 Q3.

19 Period: 2007 Q1 – 2021 Q3. Prime office space.

20 Norges Bank has previously recommended strengthening the statistical basis for commercial property (see Financial Stability Report 2018).

21 Period: Week 1 2005 – week 44 2021.

22 Period: 2005 Q1 – 2021 Q2. Market capitalisation is the market value of equity and interest-bearing debt less cash. Earnings are a four-quarter moving average of operating earnings before depreciation, amortisation and impairment. Price/book is the market value of equity in relation to the carrying amount of assets excluding intangibles. The sample is Norwegian listed companies excluding financial institutions, companies engaged in oil production etc, companies registered abroad, companies without interest bearing debt and companies presenting incomplete financial reports.

1.4 The Norwegian financial system is vulnerable to cyber attacks

Cyber attacks are a potential threat to financial stability and are thus a source of systemic risk in the financial system.23 Even though cyber attacks have affected individual institutions, so far, cyber attacks have not given rise to financial crises, either in Norway or globally. The lack of an empirical basis makes it a challenge to assess the level of this vulnerability in the financial system. At the same time, serious cyber attacks appear to be trending upwards, resulting in a need for greater attention to cyber risk and development of measures to address it.

Digitalisation and interconnectedness constitute vulnerabilities

Extensive digitalisation in the Norwegian financial system, particularly in the payment system, increases efficiency. At the same time, it entails a vulnerability to cyber attacks. Moreover, considerable financial assets, key infrastructure and large quantities of sensitive data make the financial sector an attractive target. Financial and operational dependencies mean that the consequences of cyber attacks can spread quickly and widely across the financial system.

The Norwegian financial sector has largely outsourced ICT operations and development to third-party providers. Critical functions in the financial infrastructure are dependent on a few key ICT providers (see Financial Infrastructure Report 2021). Such concentration raises the risk that a cyber attack can affect much of the financial system. Increased outsourcing of ICT services results in longer and more complex supply chains for financial institutions. Long digital supply chains provide a large number of attack surfaces, making it more difficult to monitor and manage cyber risk.

In order to perform its tasks, the financial system depends on the availability and integrity of the information in its possession. For example, payment system operators need to be able to trust account information to execute payments. This makes the system vulnerable to cyber attacks that encrypt or manipulate information. In addition, traditional contingency measures are usually also dependent on access to correct information.

A more aggressive threat landscape

The Norwegian National Security Authority (NSM) assesses the digital threat landscape as more aggressive.24 Cyber attacks on Norwegian entities are increasing in scope. Threat actors also appear to be more professional and specialised, so that the complexity of attacks is increasing. Financial institutions report to Finanstilsynet (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway) that digital attacks by criminal actors are becoming increasingly sophisticated.25 The majority of attacks on the financial sector are economically motivated. At the same time, the security authorities point out that state actors represent a serious threat to Norwegian interests, including through digital mapping and possible sabotage of critical Norwegian infrastructure, including the financial system.26

NSM considers supply chain attacks to be a growing risk. Threat actors can have a wide-ranging impact by exploiting providers’ security holes. For example, the hacking of the software developer SolarWinds and weaknesses in Microsoft Exchange have shown supply chain attacks’ considerable potential for harm. In connection with these two cases, Finanstilsynet has received notifications from Norwegian financial institutions that have been exposed to the compromised software, but no signs have been found that the security hole has been exploited.27 Nevertheless, these incidents illustrate risks related to supply chains.

Use of ransomware is increasing. The attack on the Colonial Pipeline in the US show that such attacks can have serious societal ramifications if they target key infrastructure. In Sweden, Coop had to close all of its approximately 800 stores for several days owing to a ransomware attack on Kaseya, a subcontractor for its cash register system. A more recent feature of ransomware attacks is that in addition to demanding ransom for decrypting data, attackers also demand payment for not publishing or selling sensitive data obtained in the attack. A ransomware attack on a financial institution where sensitive data fall into the wrong hands can have negative consequences for the reputation of the affected institution, but also for trust in the entire financial sector. In its threat assessment, DNB refers to ransomware as the greatest digital threat to DNB.28

Resilience to cyber attacks must be strengthened

In Financial Infrastructure Report 2021, Norges Bank considers the financial infrastructure to be secure and efficient, but points out that testing for and identifying risks of cyber incidents in the banking and payment system can be improved. In its latest review of financial sector ICT use, Finanstilsynet considers overall risk relating to cybercrime to be high. Nevertheless, Finanstilsynet points to steady improvements in financial institutions’ cyber resilience work, with attacks largely averted before they have serious consequences.

There is broad agreement both internationally and in Norway that resilience to cyber attacks in the financial system must be strengthened. In 2020, the European Commission presented a draft Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA). Existing Norwegian rules are already close to the requirements in the proposed EU regulation.29 An important new element of DORA is the introduction of a supervisory framework for ICT providers. Norges Bank has previously recommended further study of the best way to supervise key ICT providers and data centres.

In 2018, the European Central Bank (ECB) published a framework for testing entities’ ability to detect and respond to cyber attacks, Threat Intelligence-based Ethical Red Teaming (TIBER-EU). Its purpose is to strengthen the cyber resilience of financial sector entities and thus promote financial stability. Moreover, TIBER testing provides additional knowledge about how cyber attacks can affect the financial system. In collaboration with Finanstilsynet, Norges Bank has developed a framework for implementation in Norway (TIBER-NO), based on TIBER-EU.30 TIBER-NO was approved by Norges Bank’s Executive Board in September. Norges Bank will establish a Norwegian TIBER Cyber Team (TCT-NO) to administer and operationalise TIBER-NO. A steering group, of which Finanstilsynet is also a member, is tasked with ensuring that critical functions in the financial system are tested and with quality-assuring the tests. Testing under TIBER-NO is expected to be conducted in 2022 at the earliest.

Cyber attacks’ potential for systemic consequences requires a broader perspective than supervision and oversight of individual institutions and systems. It also requires expanded collaboration between various authorities and financial system participants. Cyber mapping identifies key financial and operational dependencies in the financial system, between financial institutions, the financial infrastructure and third-party providers. It provides useful insight into how a cyber incident can threaten financial stability and is also a prerequisite for monitoring systemic cyber risks and proper incident management in the event of a cyber attack.

In Norway, such work is underway to map fundamental national functions in the financial system in connection with implementing the new Security Act. Fundamental national functions are functions necessary for the government’s ability to protect national security interests.31 This mapping is to include sub-functions and the entities, systems and providers that are crucial or critical for performing these functions. This work is laying an important foundation for further management of systemic cyber risk in Norway.

23 Cyber incidents can also arise from unintended operational faults (see FSB (2018) Cyber Lexicon). Nevertheless, in a systemic risk context, the focus is often on cyber attacks, since it is considered more likely that malicious attacks can weaken trust in the financial system, even though both incident types can have serious consequences (see, eg, ESRB (2020) Systemic cyber risk).

24 See Norwegian National Security Authority (2021) Risiko 2021 [RISK 2021] (in Norwegian only).

25 See Finanstilsynet (2021) Risiko- og sårbarhetsanalyse (ROS) 2021 [Risk and vulnerability analysis (ROS) 2021] (in Norwegian only).

26 See Norwegian Police Security Service (2021) “Nasjonal trusselvurdering 2021” [National threat assessment 2021] (in Norwegian only).

27 See Finanstilsynet (2021) Risiko- og sårbarhetsanalyse (ROS) 2021 [Risk and vulnerability analysis (ROS) 2021] (in Norwegian only).

28 See DNB (2021) “Trusselvurdering 2021“ [Threat assessment 2021] (in Norwegian only).

29 See preliminary position memo on DORA in the Norwegian Government’s EEA database.

30 See Norges Bank’s press release of 21 October 2021 “Norges Bank and Finanstilsynet establish TIBER-NO framework for testing financial sector cyber resilience”.

31 More precisely, fundamental national functions are defined as “services, production and other types of activity which are of such importance that a complete or partial loss of the function would have consequences for the State’s ability to protect national security interests” (see Act relating to national security (Security Act)).

1.5 Other societal trends are important for financial stability

Climate change is creating considerable challenges in many areas, but banks are well positioned to manage the risks. Crypto-assets are not considered to be a threat to financial stability yet, either globally or in Norway. This can change in the future, but a number of regulatory initiatives can lessen the threat to financial stability.

Climate change is creating major challenges, but banks are well-positioned to address the risks

Average global temperatures have risen by around 1.1°C compared with the period 1850–1900. The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has determined that anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere are the main reason for the increase in temperatures.32

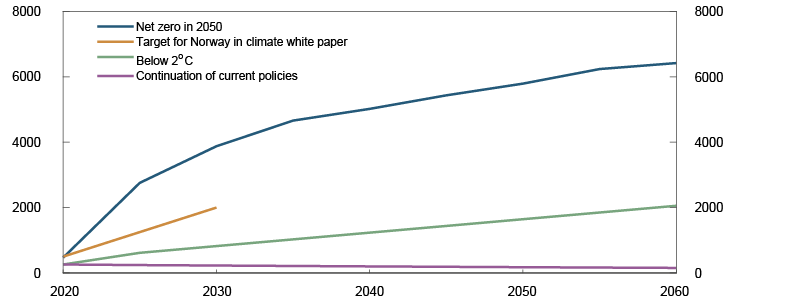

Climate change, along with mitigation policies, will have global macroeconomic consequences in the coming years.33 Both the private and public sectors must make substantial investment to cut emissions and to prepare for changes in weather patterns owing to climate change that has already taken place. The longer one waits to take action, the more expensive it is assumed that this process will be. Growth in such climate investment must come at the expense of other investment or financed by reduced net financial investment or reduced consumption.34

Norway is relatively little exposed to the adverse effects of physical climate change.35 Norway produces substantial amounts of clean energy, and Norwegian firms and households have already come far in electrifying their energy consumption. On the other hand, Norway is a major producer of oil and gas. A quick transition to less use of fossil fuels globally will place considerable demands on the energy sector’s restructuring capabilities.

By virtue of their role in credit intermediation, banks have an important function in allocating capital to new projects. Banks must further develop their credit assessments to make them better able to evaluate firms’ exposure to climate change and increased climate risk. The authorities can contribute by requiring more standardised reporting.

At the same time, climate change can increase the risk of losses on existing exposures. This can be due to transition risk, ie firms are unable reduce emissions from their operations, and physical risk, ie losses resulting from damage caused by climate change. There is reason to believe that climate change will have a more profound impact on equity investments, which reflect firms’ long-term returns, than on loans, which normally have a shorter horizon and are secured with collateral. Our analyses show that Norwegian banks have moderate exposures to firms with large climate exposures (see "Norwegian banks’ exposure to climate risk"). Norwegian banks have limited exposures to carbon-intensive industries. In addition, climate change can affect regulation and market requirements, which may be of importance for bank funding (see "Forthcoming climate-related reporting").

Growing use of crypto-assets requires new regulations

Crypto-assets encompass a number of asset types. Besides the best known cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, crypto-assets also include various digital representations of assets (“tokens”). Tokens use cryptocurrency systems as an infrastructure for issuance and trading. One type of crypto-asset is “stablecoins”, which aim for a stable value against a benchmark, normally a national currency, with the US dollar the most used. The use of cryptocurrency systems as financial services platforms is often referred to as decentralised finance.

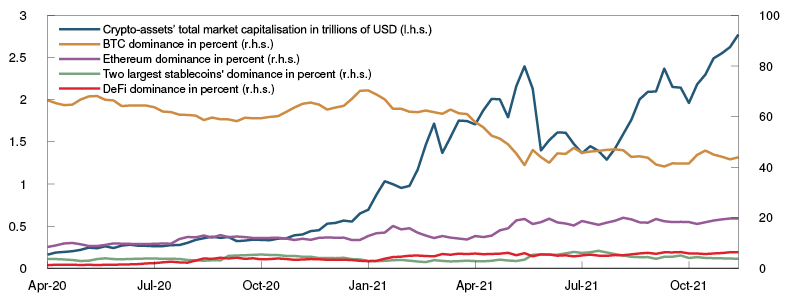

The total market capitalisation of all crypto-assets has been relatively volatile during 2021 (Chart 1.15). Periodically, the market capitalisation has been over USD 2 000bn, of which Bitcoin accounts for just over 40%, while stablecoins account for around 5%. Bitcoin’s share of crypto-assets’ total market capitalisation has fallen so far in 2021, among other reasons because the volume of cryptocurrencies used as infrastructure for decentralised finance has risen.

Chart 1.15 Crypto-assets market capitalisation has fluctuated considerably in 202136 Total market capitalisation of crypto-assets and market shares of different crypto-assets

Cryptocurrencies began as an underground phenomenon for payments about 10 years ago, but quickly assumed a role as a speculative investment. The development of stablecoins has enabled greater use of crypto-assets for payments, but there are still few transactions other than crypto-asset trades. It is likely that speculation is still an important driver of valuations and the substantial swings in cryptocurrency values. Social media and tech platforms have fuelled market hype and simplified crypto-asset transactions. The IMF does not consider crypto-assets to be a risk to global financial stability yet, but recommends that developments should be monitored closely.37

Institutional investors have shown a growing interest in crypto-assets, both globally and in Norway. Surveys show that the possibility of substantial gains is also a key motivator for institutional investors.38 Internationally, banks and other traditional financial institutions are also considering the possibility of exposing their balance sheets to crypto-assets and of offering customers related services. To our knowledge, Norwegian banks and other Norwegian financial institutions do not have material exposure to crypto-assets.

Crypto-assets can fall sharply in value, and the falls in value can be sudden and unpredictable, eg, if the assumptions regarding the technology fail. A substantial fall in the value of crypto-assets can have ripple effects on the financial system, if banks and other systemically important institutions are significantly exposed. The Basel Committee has drafted a proposal for capital requirements for banks exposed to crypto-assets.39 This proposal mainly entails that if banks wish to hold unhedged crypto-assets on their balance sheets, the assets must be fully financed by equity. This substantially reduces the risk of ripple effects on the financial system caused by large price falls.

Global stablecoins may become systemically important if they become widespread. Stablecoins can be secured in various ways. Some are secured on more or less liquid assets, while others are secured on other crypto-assets. Stablecoins secured on securities share similarities with money market funds, and in the event of uncertainty regarding the cryptocurrency’s value, may be subject to large scale conversions to another currency by investors. In that case, the underlying securities need to be quickly liquidated to pay those wanting to convert. Such a fire sale of securities can have systemic effects. The Financial Stability Board (FSB) has formulated overall principles for regulating global stablecoins.40 In the EU there is work on extensive regulation of crypto-assets, which also includes regulation of stablecoin providers41. The regulation seeks to promote innovation, protect consumers and protect financial stability.

Crypto-assets can also affect financial stability by affecting payment system security. If crypto-assets are used for payments in sufficient volume, technical failures can have systemic effects. There may therefore be a need for special regulations that address risk related to the use for payments in the same way as traditional payment systems are regulated. Financial Infrastructure Report 2021 discusses such regulations in detail. The Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) are working on principles for stablecoins used for systemically important stablecoin arrangements.42 The principles are meant to address some of the challenges mentioned above and may mean, for example, that certain stablecoins cannot be used for systemically important transactions.

Crypto-assets can also lead to less use of national currencies,43 affecting the ability to conduct monetary policy, for example. This is primarily a challenge for countries with fairly inefficient payment systems, lack of trust in the monetary system and unstable currencies. This is therefore considered to be a small risk for Norway in the foreseeable future.

32 See IPCC (2021) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

33 See eg Pisani-Ferry, J. (2021) “Climate Policy is Macroeconomic Policy, and the Implications Will Be Significant”. PIIE Policy Brief 21-20.

34 See eg Fæhn, T., K.R. Kaushal, H. Storrøsten, H. Yonezawa and B. Bye (2020) “Abating greenhouse gases in the Norwegian non-ETS sector by 50 per cent by 2030”. Reports 2020/23. Statistics Norway.

35 Germanwatch, which compiles the Global Climate Risk Index, intended to measure risks of effects of extreme weather, ranks Norway as 149th out of 180 countries on its vulnerability index for 2000–2019 (see Eckstein, D., V. Künzel and L. Schäfer (2021) “Global climate risk index 2021”. Briefing Paper. Germanwatch, January 2021).

36 Period: Week 14 2020 – week 45 2021.

37 See International Monetary Fund (2021) “Covid-19, Crypto and Climate”. Global Financial Stability Report. IMF, October 2021.

38 See Fidelity Digital Assets (2021) “The Institutional Investor Digital Asset Study”. September 2021.

39 See BCBS (2021) “Prudential treatment of crypto-asset exposures”. Consultative Document. BIS, June 2021.

40 FSB (2020) “Regulation, Supervision and Oversight of ‘Global Stablecoin’ Arrangements”. FSB, October 2020.

41 Referred to as the Markets in Crypto Assets (MiCA) Regulation.

42 CPMI-IOSCO (2021) “Application of the Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures to stablecoin arrangements”. Consultative Report. BIS, October 2021.

43 See International Monetary Fund (2021) “Covid-19, crypto and climate”. IMF, October 2021.

Norwegian banks’ exposure to climate risk

Climate change has a range of consequences for Norway. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions must be reduced markedly, businesses must restructure and Norway must prepare for changes in weather patterns. For banks, this may result in higher losses. Climate risks are normally grouped into two categories: Transition risks may lead to increased bank losses owing to society’s adaptation to lower GHG emissions, while physical risks are potential losses owing to climate change. Norwegian banks’ direct exposure to transition risks appears to be moderate, and so far, exposure to known physical risks appears to be limited. In view of this, combined with their financial solidity, Norwegian banks are well positioned to meet the challenges of climate change.

Norwegian banks have moderate direct exposure to transition risks as a result of higher carbon prices

With higher carbon prices, the ability to reduce GHG emissions will be an important factor in cost management and profitability. As high-emission firms will need the most extensive restructuring, banks will be most exposed to transition risks from their lending to these firms. Assessment of GHG emissions and climate mitigation measures will be an important factor in assessing long-term profitability.

In recent years, the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)1 has established norms for the disclosure of climate-related information at firm level. The TCFD recommends that emissions should be reported in three so-called scopes:

•Scope 1 refers to all direct GHG emissions.

•Scope 2 refers to indirect emissions from consumption of purchased electricity, heat or steam.

•Scope 3 refers to other indirect emissions not covered in Scope 2 that occur in the value chain of the reporting company.

Firms are also required to report their plans to reduce GHG emissions. So far, companies complying with TCFD reporting requirements are primarily large listed companies. Norwegian banks’ exposures are mainly to small and medium-sized enterprises. For the time being, reporting does not provide an accurate picture of these firms’ emissions. Regulation of reporting standards is under development (see "Forthcoming climate-related reporting").

To obtain a picture of Norwegian banks’ exposure to high-emitting firms, Scope 1 emissions data by industry is linked to firms’ turnover data from Statistics Norway.2 Emissions measured in CO2 equivalents3 as a share of turnover across 45 different industries can then be calculated. For industries with high Scope 2 and 3 emissions, this will underestimate the emissions. For Norway as a whole, this applies to oil and gas extraction in particular, which has high Scope 3 emissions, but this industry accounts for less than 5% of Norwegian banks’ lending to the corporate sector.

Particularly vulnerable exposures are assumed to be in industries where carbon prices will increase most as a share of total turnover in the years ahead. Higher carbon prices do not in themselves entail financial risk. A firm can maintain its earnings if it is able to reduce emissions or increase prices. However, for these firms, carbon emission management will be an increasingly important factor to ensure continued solid profitability and debt-servicing capacity.

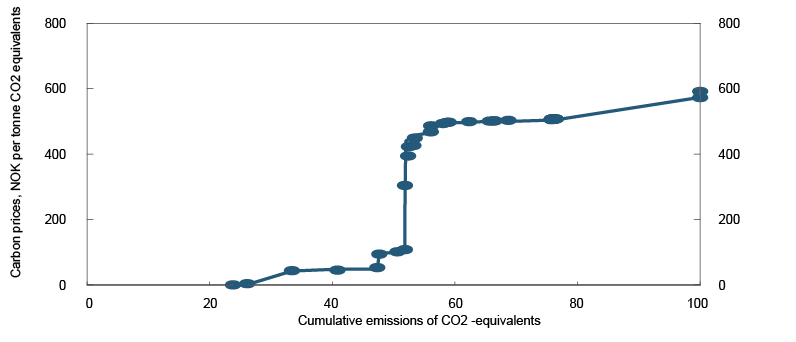

The current cost of GHG emissions varies widely across industries (Chart 1.E).4 Carbon prices are expected to increase, also in industries where carbon taxes are currently low. The Government’s climate action plan presented in 2021 set a target for the carbon tax of NOK 2 000 per tonne CO2 equivalents by 2030. The climate scenarios of the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System (NGFS)5 show that it is necessary to have a global carbon price higher than this to meet the goal of the Paris Agreement6 to work toward limiting global warming to 1.5°C (Chart 1.F).

Chart 1.E Many industries continue to pay low carbon prices7 Carbon prices by cumulative share of emissions for 45 industries. Volume-weighted average by industry. NOK per tonne CO2 equivalents. Data for 2019

Chart 1.F Carbon prices to rise in the coming years8 Carbon prices in different model forecasts. EU-28. NOK per tonne CO2 equivalents

The impact at industry-level of a rise in the carbon price to NOK 2 000 for all industries has been assessed. In 31 of the 45 industries, the carbon price increase will be equivalent to less than 1% of turnover in 2008. The cost of the increase is highest in international shipping and agriculture, followed by the process industry, transport and oil and gas extraction.

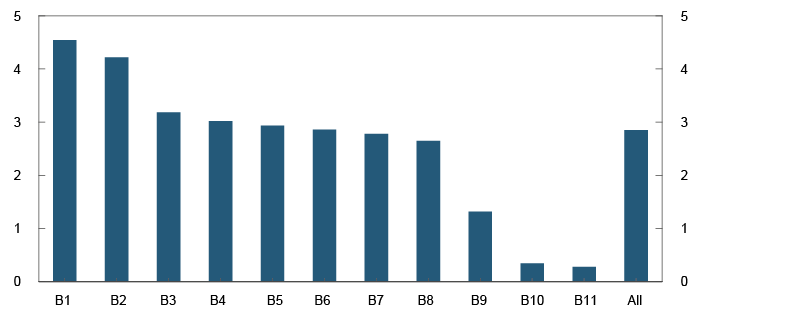

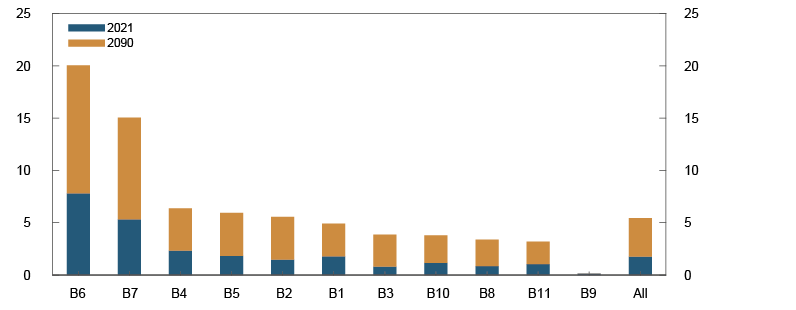

Overall, the most exposed industries account for slightly more than 20% of banks’ total corporate lending9, about half of which is shipping loans. Banks with large shipping exposures are in relative terms most exposed to climate risk. The size of the exposures varies widely across the 11 banks (Chart 1.G). Some of the foreign banks operating in Norway have transferred the majority of their shipping exposures to their Norwegian branches, which therefore appear to have higher climate exposure than implied by the bank’s overall climate exposure.

Chart 1.G Considerable differences in banks’ exposures to high-emission industries10 Increased carbon taxes as a share of banks’ customers measured at industry level. Weighted by share of banks’ exposure to the industry. Eleven largest banks. Percent. Data for 2019

Even though shipping is a high-emission industry and may face a marked increase in price, the industry as a whole is in a good position to meet new climate policy requirements. The price sensitivity of shipping services demand is likely relatively low, and there may be considerable potential for reducing direct emissions from ships. On the other hand, close to half of Norwegian banks’ shipping exposures are related to either oil and gas transport or to ships used in connection with oil production, and the need for restructuring in these firms may be higher. We find that Norwegian banks submit climate-related disclosures in line with TCFD requirements for about 1/3 of their total lending to shipping.

Norwegian banks have little exposure to known physical climate risks

Physical climate risk is the risk of damage resulting from climate change such as extreme weather events, higher sea levels or generally higher temperatures. Climate change can have direct consequences, such as increased risk of flooding or forest fires, and indirect effects, such as changes to biological systems. In many cases, the consequences of physical climate risk can be reduced through preventative investment. Nevertheless, there is considerable uncertainty about the long-term effects of climate change.

Banks are exposed to physical climate risk through losses on exposures to firms that sustain damage. Damage can also affect the value of physical collateral used to back exposures. Banks’ risk is reduced if the collateral is insured. In Norway, property affected by natural disaster is protected by the Norwegian National Scheme for Natural Damage Assistance, which is a group insurance scheme with government contributions.11 Insurance under this scheme only covers the cost of restoring property to its pre-disaster condition. If the likelihood that the damage will recur is high, the value of the property may be permanently reduced. If physical risks increase, there is reason to expect natural disaster insurance premiums to increase over time.

It is possible to predict to some extent the areas that will be most vulnerable to direct damage. Storm surges affect coastal property. The risk of flooding is linked to terrain featuring waterways, while the risk of avalanches and landslides is mainly associated with ground conditions. These conditions have been mapped by the Norwegian authorities. Maps of vulnerable areas are available from the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE).12