Executive Board’s assessment

In the Financial Stability Report, Norges Bank assesses vulnerabilities and risks in the Norwegian financial system and points to measures that can contribute to financial stability. The Executive Board discussed the content of the Report on 18 September and 23 October.

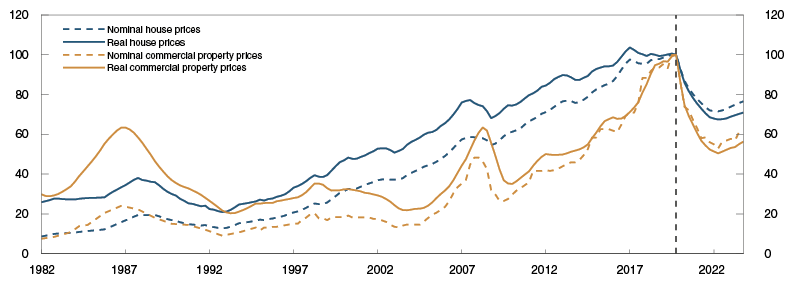

Financial system vulnerabilities in Norway have not changed substantially since the previous Report, which was published in October 2018. Household debt is high, and commercial and residential property prices are at high levels after rising sharply over a long period. However, over the past two years, debt growth and house price inflation have been more moderate than previously, and house prices have risen more slowly than disposable income. Over the past year, the rise in commercial property prices has also slowed, and household debt is now rising at close to the same rate as disposable income. Norwegian banks have maintained profitability and solvency and continue to have ample access to funding.

Global economic uncertainty poses a risk to financial stability in Norway. Events in the international economy and financial markets can spread to Norway, and the impact in Norway may be amplified by domestic financial system vulnerabilities. Two such contagion channels are Norwegian exports and banks’ foreign funding. The trade tensions between the US and China remain a source of uncertainty and the UK’s relationship with the EU remains unclarified. Over the past year, uncertainties surrounding growth prospects abroad have led to a broad decline in interest rates. Persistently low interest rates may give rise to high risk-taking and financial imbalances. So far, global uncertainties have not had serious consequences for the Norwegian economy, and Norwegian banks have felt little impact, but this situation can change quickly.

On balance, the financial stability outlook is broadly unchanged since the 2018 Report.

The Norwegian authorities have implemented a number of measures to mitigate financial system vulnerabilities. Requirements for banks’ credit standards limit excessive borrowing by the most vulnerable households. The regulation on new residential mortgage loans, first introduced in 2015, was tightened in 2017 and has functioned as intended. Norges Bank is of the opinion that debt growth and housing market developments do not warrant material changes to the requirements and in a consultation response on 14 October supported continuation of the regulation. There are also signs that measures targeting the consumer credit market have dampened consumer debt growth. In addition, the registers of unsecured debts, which were introduced on 1 July, have given banks more complete data on which to base credit assessments. Such registers should also include information on collateralised loans to enable banks and loan applicants to easily obtain the full picture of a loan applicant’s debt situation.

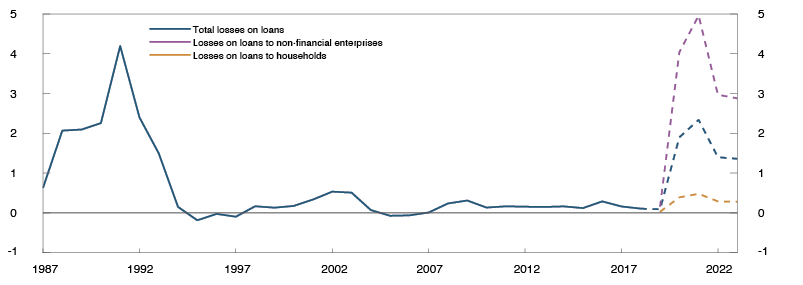

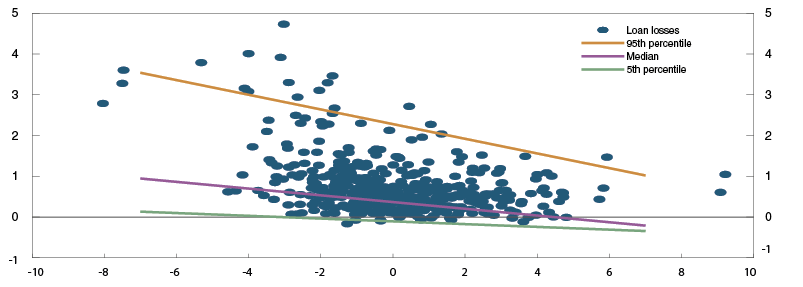

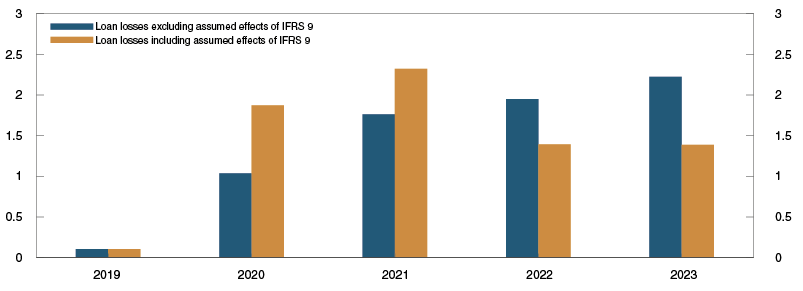

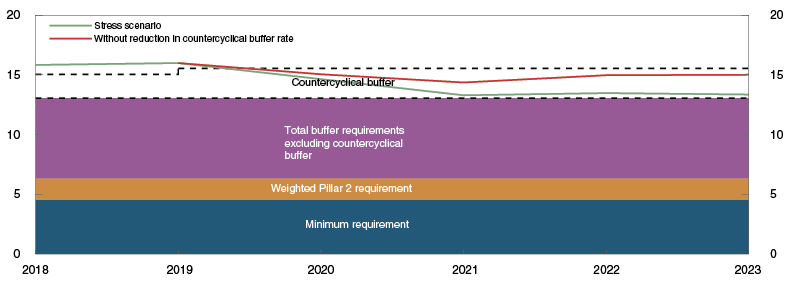

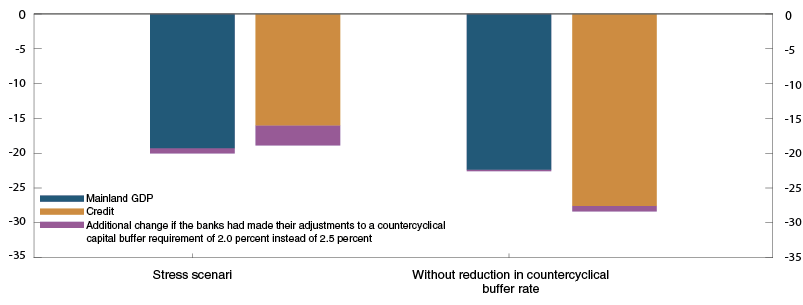

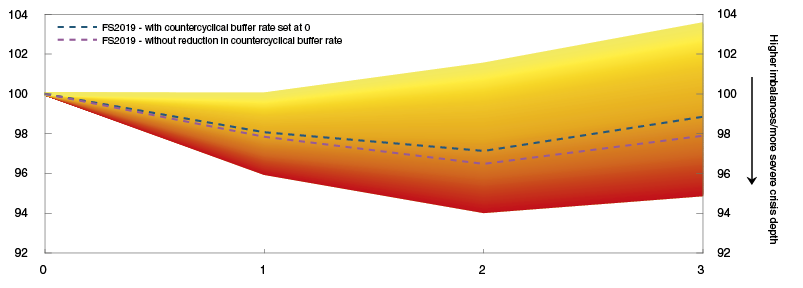

Banks’ loss absorbency capacity in an economic downturn is important for financial stability. Banks’ capital and liquidity requirements have become considerably stricter following the financial crisis. The stress test in this Report shows that the capital buffers of the largest Norwegian banks as a whole are sufficient to absorb the losses associated with a hypothetical downturn in the Norwegian economy. Nevertheless, in such a situation, banks may still tighten lending, which may amplify the downturn. To counter a sudden fall in lending, the authorities can reduce the countercyclical capital buffer and allow banks to draw on the remaining buffers. In that case, banks should be given sufficient time to rebuild the capital buffers.

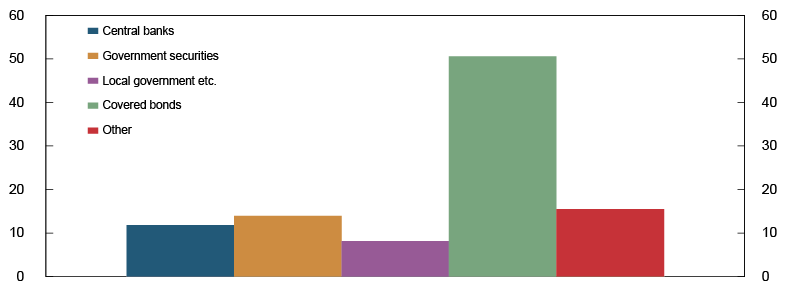

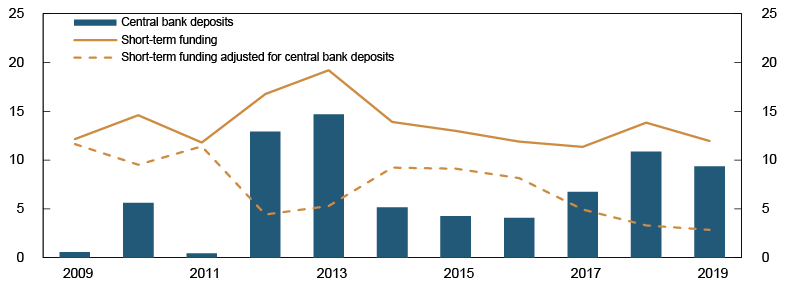

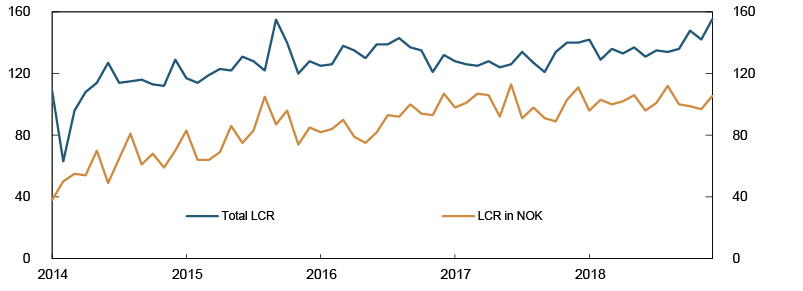

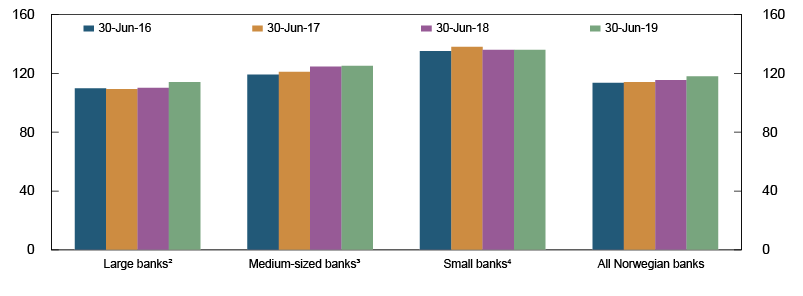

In connection with the implementation of the remainder of the EU capital framework, many banks’ reported capital ratios will rise without this reflecting an improvement in solvency. Norges Bank is of the view that in the current situation, Norwegian banks’ capital levels should not be reduced. Structural systemic risk is high, particularly owing to high household leverage. Since the systemic risk buffer was introduced in 2013, banks have increased their property market exposures, and their cross-holding of covered bonds has also risen. In its consultation response on 30 September, Norges Bank supported as a countermeasure the proposal to increase the systemic risk buffer, an action that will help banks to maintain loss absorbency.

Financial stability considerations in each country should determine the scope of regulation, whether the lenders are domestic or foreign banks. Foreign banks’ share of the Norwegian market is high. It is therefore important that other countries recognise Norwegian regulations and vice versa.

Digital vulnerabilities may result in a higher risk of operational problems. Cyber attacks are becoming increasingly widespread and sophisticated. Moreover, the financial system depends on a few critical ICT service providers. This increases the risk that a cyber attack may pose a threat to financial stability. Finanstilsynet and Norges Bank have invited the industry and other relevant authorities to a dialogue to assess whether the European framework for Threat Intelligence-based Ethical Red Teaming (TIBER-EU) would be suited to Norway. In its consultation response on the ICT security bill, Norges Bank pointed out a need for further study of the best way to supervise critical ICT service providers and data centres.

Climate change and society’s adaptation to climate change will affect all segments of the economy and entail risks to financial stability. Changes in climate regulation, new technology and changing investor and consumer preferences may entail a transition risk for the Norwegian economy in the coming years, a risk amplified by the importance of the oil and gas industry for Norway. Climate change is a global challenge, which must primarily be addressed by the political authorities and instruments other than those available to central banks. Climate risk must be managed in the same way as other risks facing the financial sector. The instruments for strengthening banks’ resilience, such as capital requirements and prudential supervision, are thus basically the same as those used for managing other risks. Central banks and supervisory authorities can, within their mandates, promote financial stability by helping to pave the way for the financial sector to include climate risks in overall risk assessments and communicate relevant information and by ensuring adequate capital to support all risks.

The key vulnerabilities in the financial system in Norway are high household debt, high house prices and high commercial property prices. Vulnerabilities have not changed substantially since Financial Stability Report 2018. Norwegian banks have maintained profitability and solvency and continue to have ample access to funding. Global economic uncertainty poses a risk to financial stability in Norway. Over the past year, uncertainties surrounding growth prospects abroad have led to a broad decline in interest rates. Persistently low interest rates may give rise to high risk-taking and financial imbalances. On balance, the financial stability outlook is little changed since the 2018 Report.

Since the financial crisis, the Norwegian authorities have introduced a number of measures to mitigate the risks in the financial system. The most important are stricter bank capital and liquidity requirements. Requirements for banks’ credit standards limit excessive borrowing by the most vulnerable households.

1.1 Risk of external shocks

Global turbulence can spread

The financial system largely operates across borders. Global turbulence and uncertainty may therefore spread to the financial system in Norway both from the global financial system and via the real economy. Small open economies like Norway are especially at risk. The IMF works to uncover financial sector vulnerabilities and provides advice on measures to address them (see "IMF assessment of the Norwegian financial system").

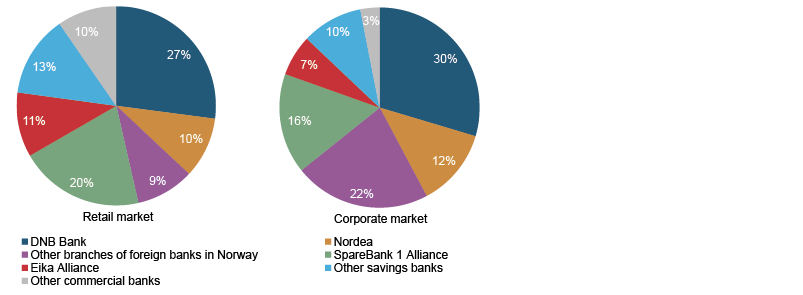

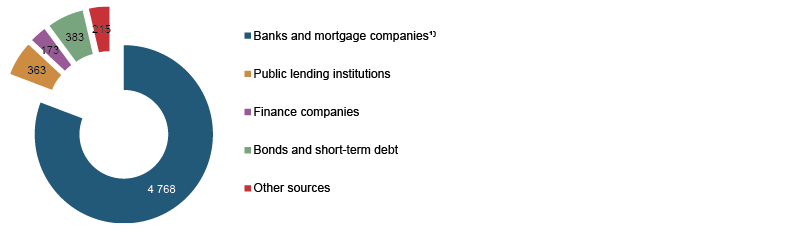

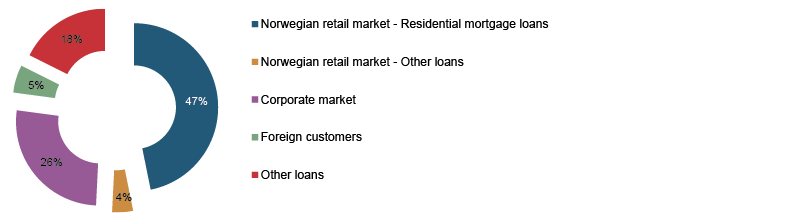

Large Norwegian banks obtain large amounts of funding abroad. At the same time, foreign banks account for around a quarter of all lending in Norway. Global financial turbulence may raise Norwegian banks’ funding costs and lower the supply of credit from foreign banks in Norway, both of which can reduce households’ and firms’ access to credit. Large firms that rely on the global bond market for financing may also be directly affected. Global turbulence has had little impact on Norwegian banks since the 2018 Report.

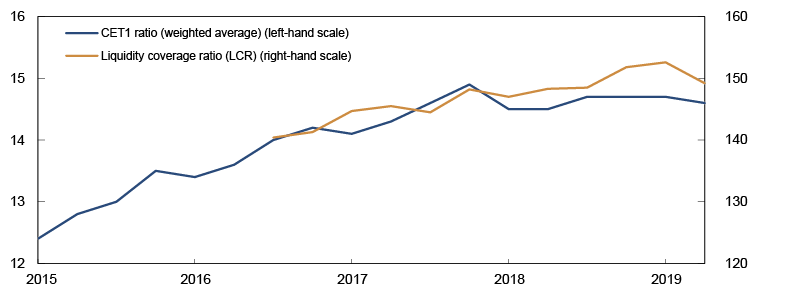

The European market is particularly important for the Norwegian economy. The situation at European banks is important for the European economy and may affect Norwegian banks’ funding markets. On the whole, European banks’ capital adequacy and liquidity coverage have improved considerably in recent years (Chart 1.1), but there are large differences across countries. The build-up of loss absorbency capacity appears to have come to a halt, and the average leverage ratio is lower for European banks than for Norwegian banks.1

Chart 1.1 Capital and liquidity coverage ratios in the EU banking system Weighted average. Percent. 2015 Q1 – 2019 Q2

Source: European Banking Authority (EBA)

A large share of Norwegian financial institutions’ settlement takes place in foreign interbank systems, and large volumes of derivatives are cleared via UK central counterparties (CCPs). The UK’s withdrawal from the EU may entail challenges for these transactions. Temporary measures allow Norwegian firms to participate in UK CCPs even in the event of a no-deal Brexit.

IMF assessment of the Norwegian financial system

The global financial system is interconnected. Through the Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) works to uncover vulnerabilities among its members. On the basis of FSAP findings, the IMF issues advice on measures to strengthen the financial system in each jurisdiction and reduce the risk of cross border contagion of financial distress. The IMF performs thorough analyses of the most important jurisdictions, including Norway, every five years. The results of an ongoing FSAP assessment of Norway will probably be published in the course of 2020 Q2.

Weaker growth expectations and lower foreign interest rates

Uncertainties surrounding trade tensions and the UK’s withdrawal from the EU have weighed on growth prospects for Norway’s trading partners (see Monetary Policy Report 3/19). So far, there are few signs that global uncertainties have damped growth in Norwegian exports. In August, enterprises in Norges Bank´s Regional Network reported continued solid export growth, despite increased uncertainties and Brexit-related turbulence.

Global markets have long priced in monetary policy normalisation and higher global interest rates, but the uncertain global outlook has contributed to a sharp fall in risk-free long-term interest rates, which are now at very low levels in some countries (Chart 1.2). Central bank measures have also contributed to lower interest rates. Around 30% of advanced economy sovereign bonds outstanding are now trading at negative yields.2 In a number of countries, new long-term corporate and household loans are now available at negative interest rates.

Chart 1.2 Yields on ten-year government bonds in selected countries Percent. 1 January 2012 – 30 October 2019

Source: Bloomberg

Following the global financial crisis in 2008, lower interest rates have contributed to higher non-financial sector debt. Corporates have increased debt by nearly 20% of global GDP since 2008. This debt will be more vulnerable if firms’ debt servicing capacity is weakened in pace with weaker growth prospects. Global public debt has also risen substantially, while household debt is little changed. Since 2016, the global total debt-to-GDP ratio has levelled off, for both the public sector and non-financial enterprises.

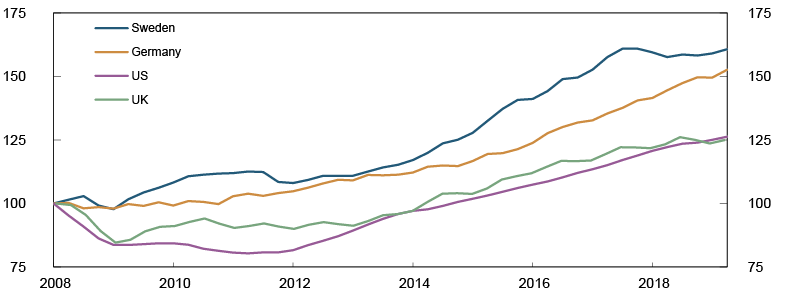

Low returns on low-risk investments have for some time contributed to higher prices for securities and real estate. Global equity prices are broadly at the same level as one year ago (Chart 1.3). Lower growth prospects have pulled down equity prices, while lower interest rates have pushed them up. Global house price inflation has been high since the financial crisis (Chart 1.4).

Chart 1.3 Stock market indexes in selected countries Index. 1 January 2008 = 100. 1 January 2008 – 30 October 2019

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 1.4 House prices in selected countries Index. 2008 Q1 = 100. 2008 Q2 – 2019 Q2

Source: Bank for International Settlements (BIS)

Low interest rates over a longer period may weaken the financial stability outlook because they fuel increased debt accumulation and asset price inflation.

1 In recent years, the average leverage ratio for EU banks has varied between 5.3% and 5.6% (see the EBA Risk Dashboard).

2 See International Monetary Fund (2019) “Global Financial Stability Report, October 2019”.

1.2 Vulnerabilities in the financial system in Norway

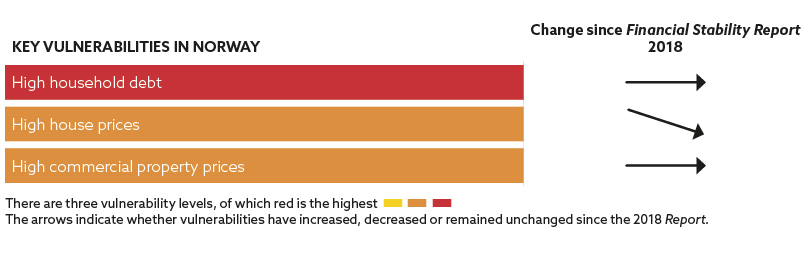

The key vulnerabilities in the financial system in Norway are high household debt, high house prices and high commercial property prices (see "Key financial system vulnerabilities in Norway"). Vulnerabilities have not changed substantially since the 2018 Report.

Over the past three years, growth in the Norwegian economy has been solid. The global upturn, low interest rates, improved cost-competitiveness, largely owing to a weaker krone, and higher oil prices have given a boost to activity.

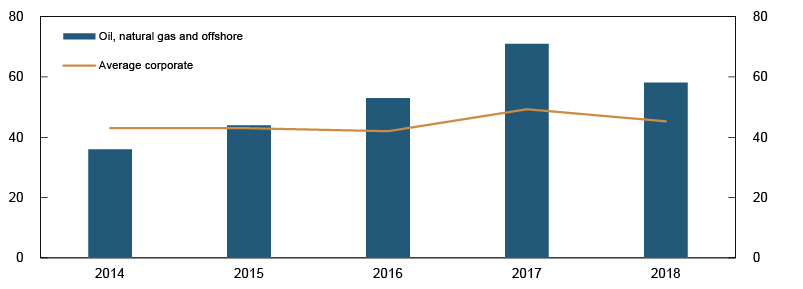

Stable net interest income and low credit losses have enabled the large Norwegian banks to maintain profitability over the past year. All Norwegian banks satisfy the capital requirements. Further ahead, the risk of higher losses among oil-related companies and stronger competition from foreign banks and other operators could pose a threat to profitability.

Key financial system vulnerabilities in Norway

The table above shows Norges Bank’s assessment of the key vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system. Vulnerabilities can be time-varying or the result of permanent structural conditions in the financial system. Vulnerabilities can cause or amplify financial turbulence and an economic downturn when the economy is exposed to large shocks. The interaction between shocks and vulnerabilities can result in financial crises that restrain economic growth. Shocks that trigger financial crises can be difficult for the authorities to predict and influence. Shocks to a small open economy like Norway will often originate in other countries.

The vulnerability assessment is based on historical experience of what causes downturns and financial turbulence and assessments of new features of the financial system. The vulnerabilities identified as key vulnerabilities may change over time.

If vulnerabilities are categorised as orange or red, Norges Bank will consider issuing advice on measures to address them. These may be measures aimed at reducing the vulnerabilities directly or increasing financial system resilience. The authorities have already implemented a number of measures (Table 1.1).

Owing to high household indebtedness and house price overvaluation, the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) has issued a warning to Norway,1 in which it points out that the vulnerabilities are a source of systemic risk to the financial system.

High household debt

Vulnerabilities related to household debt are high and broadly unchanged since the 2018 Report. High household debt will amplify the negative outcome of a sudden and sharp movement in interest rates, house prices or household income. Most households have room to defer principal repayments, draw on financial buffers or tighten consumption if they are exposed to economic shocks. The danger that a large number of households will tighten consumption at the same time constitutes a systemic risk. This may reduce firms’ earnings and debt-servicing capacity, leading in turn to higher losses on banks’ corporate exposures.

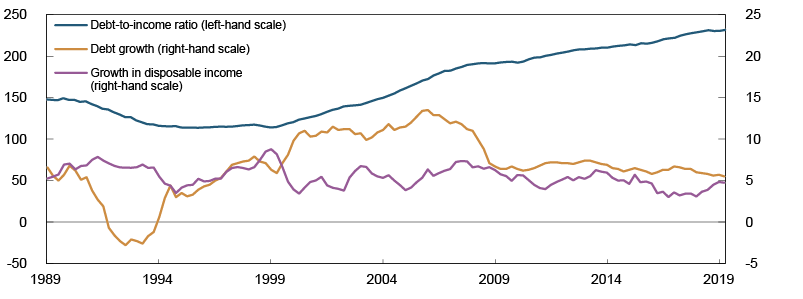

Household debt has long risen faster than household income, resulting in increasing household leverage (Chart 1.5). Household debt-to-income ratios are now showing signs of levelling off. Over the past few years, debt growth has edged down, while growth in household disposable income has risen. The higher interest rate level and continued moderate house price inflation are expected to restrain debt growth further (see Monetary Policy Report 3/19).

Chart 1.5 Household debt-to-income ratio1 and four-quarter change in debt and disposable income2 Percent. 1989 Q1 – 2019 Q23

1) Loan debt as a percentage of disposable income.

2) Income after taxes and interest payments. Adjusted for a break in the series. Four-quarter change in moving sum for the previous four quarters.

3) Projection for change in disposable income for 2019 Q2.

Sources: Statistics Norway and Norges Bank

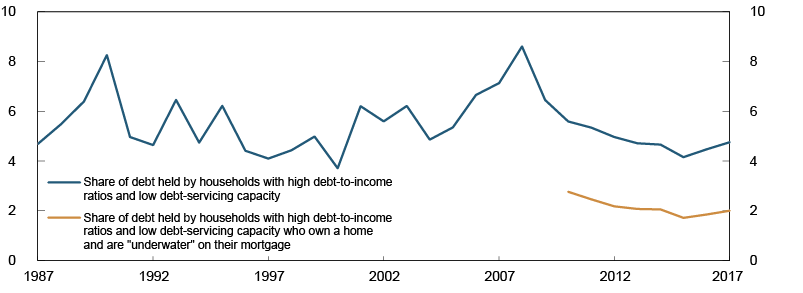

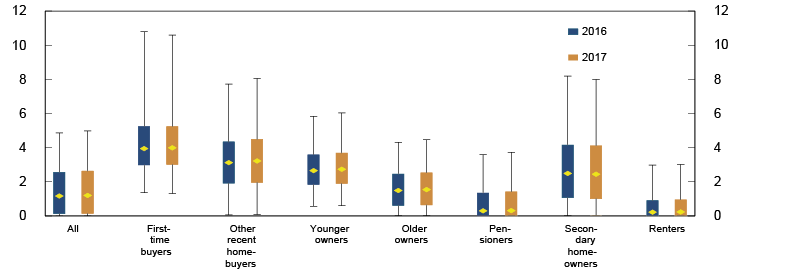

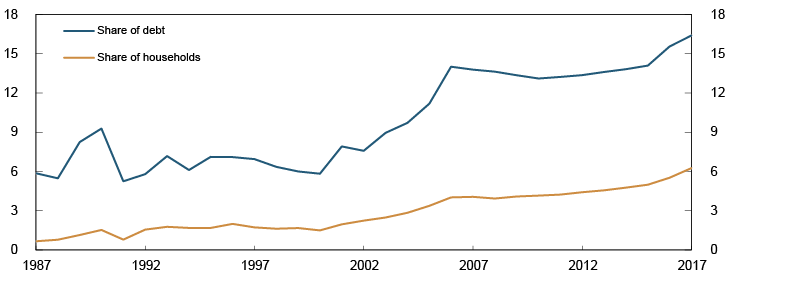

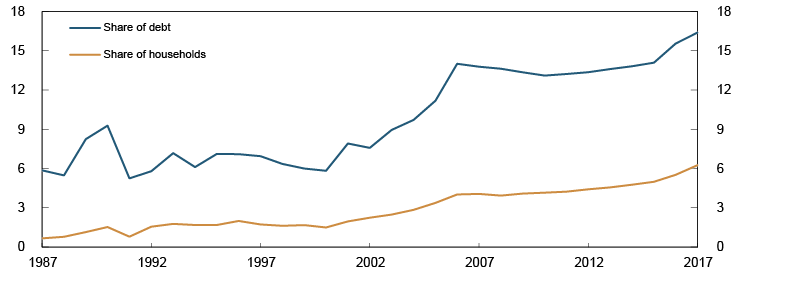

The latest available data at individual level show an increase in the share of highly leveraged households (debt above five times gross income) and low debt-servicing capacity (annual margin below one month’s income) between 2016 and 2017 (Chart 1.6). Especially among first-time buyers, there was a large share that assumed debt corresponding to a debt-to-income (DTI) ratio of above five in 2017 (see "Higher share of highly leveraged households"). DTIs also rose for households that were not active in the housing market, many of whom experienced a fall in income. The share of households “underwater” (net debt higher than their dwelling’s market value) was broadly unchanged. The data suggest that the number of vulnerable households increased between 2016 and 2017. Since then more moderate credit growth and house price inflation has been observed, which may indicate a slowdown in the build-up of vulnerabilities.

Chart 1.6 Debt held by vulnerable households1. Share of total household debt. Percent. 1987 – 2017

1) Households in breach of critical values for debt-to-income ratio (debt over five times gross income) and debt-servicing capacity (annual income after tax, less interest and standard consumption expenditure of less than one month’s income) and from 2010 also critical value for debt-to-value (net debt higher than dwelling’s market value).

Sources: SIFO, Statistics Norway and Norges Bank

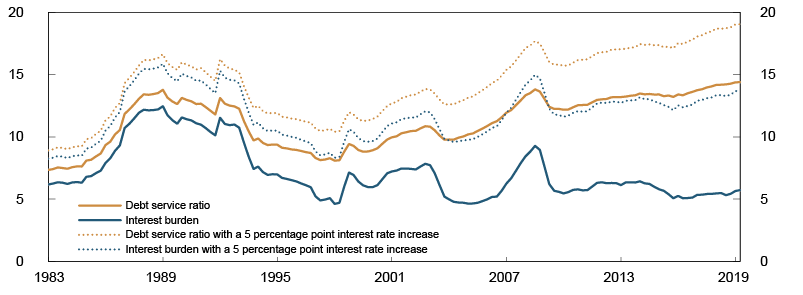

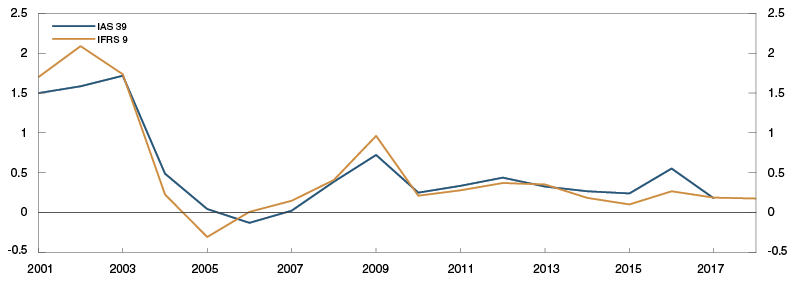

Interest burdens, ie the share of income used to service interest on debt, are historically low owing to low lending rates (Chart 1.7). After the interest rate hikes over the past year, interest burdens have risen slightly. Owing to high debt levels, interest rate increases have a greater impact on household interest burdens than before. Debt service ratios, ie the share of income used to service interest and normal principal repayments, are already high and at the same level as prior to the financial crisis in 2008 and the banking crisis in the 1990s. Debt service ratios signal high risk in the heatmap (see "Developments in the heatmap").

Chart 1.7 Household debt service ratio1 and interest burden2

Percent. 1983 Q1 – 2019 Q2

1) Debt service ratio is interest expenses and estimated principal payments as a percentage of after-tax income.

2) Interest burden is interest expenses as a percentage of after-tax income.

Sources: Statistics Norway and Norges Bank

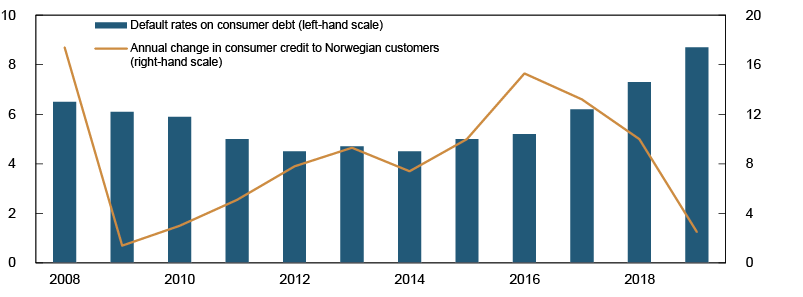

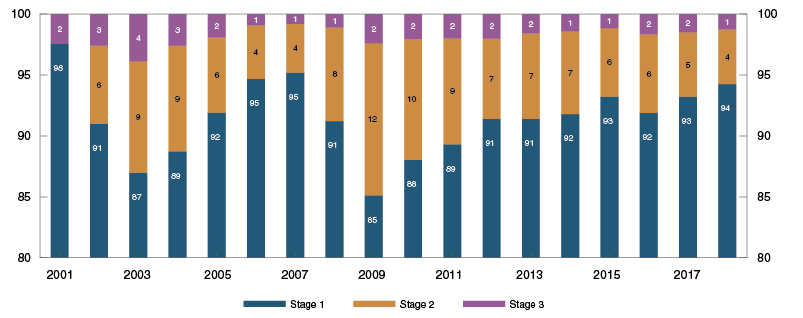

Consumer debt accounts for only 3%-4% of total household debt. Households with large consumer debt are therefore faced with high interest burdens owing to the high interest rates and consumer credit. Default rates on consumer debt are high and rising (Chart 1.8). More restrictive credit standards and reduced house price inflation may result in increased defaults among persons needing to refinance maturing consumer debt. Information from the new credit registers shows that there are many with little consumer debt, while relatively few owe large amounts (see "Credit register data show uneven distribution of consumer debt"). Growth in consumer credit to Norwegian households has long been high and rising, but has slowed since peaking in 2016.3 Lower growth reflects in part the introduction by the authorities in recent years of a number of measures to regulate consumer credit.4 The consumer credit regulation and credit registers may curb consumer credit growth further.

Chart 1.8 Annual change in consumer credit and default rates1 on consumer debt2 Percent. At year-end. 2008 – 20193

1) Gross non-performing consumer debt (90 days) as a share of gross consumer debt. Also includes finance companies' exposures abroad.

2) Based on the FSAs sample of banks and finance companies that cover most of the consumer credit market. Non-performing loans sold omitted from the sample.

3) At 30 June 2019.

Source: Finanstilsynet (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway)

The credit registers provide details on an individual’s unsecured debt. Norges Bank recommends enlarging the registers to include information on secured debt. This will provide a more comprehensive picture of a loan applicant’s debt situation.

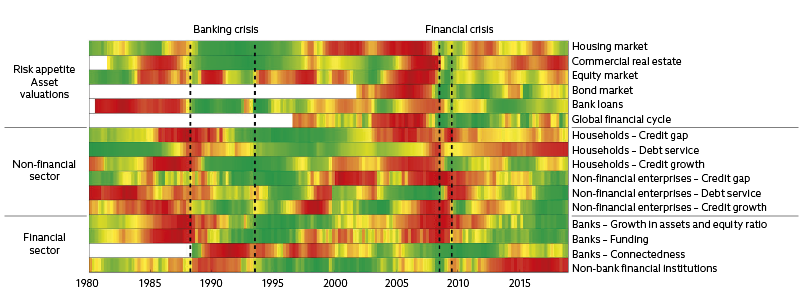

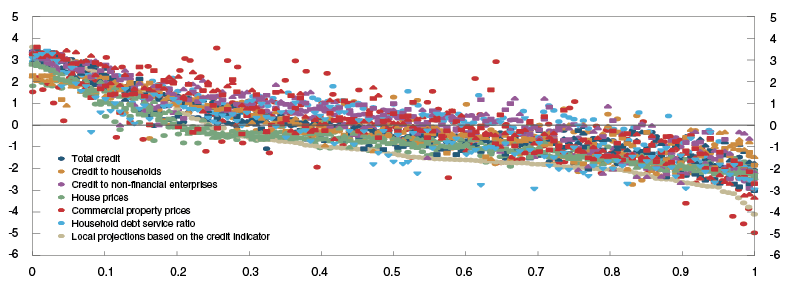

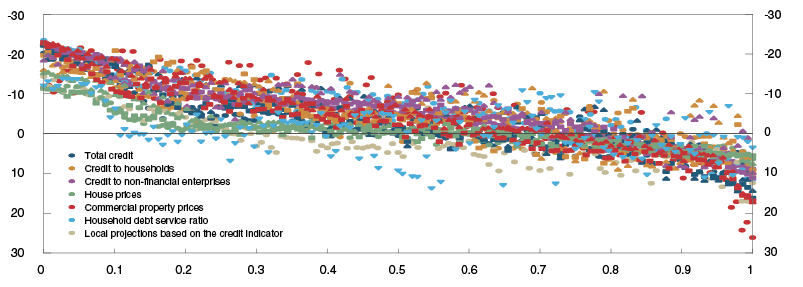

Developments in the heatmap

Norges Bank’s heatmap1 is one of a number of tools for assessing systemic risk in the Norwegian financial system. The heatmap monitors a broad set of indicators in three main areas: risk appetite and asset valuations, non-financial (household and corporate) sector vulnerabilities and financial sector vulnerabilities. Its primary objective is to measure cyclical or time-varying movements in vulnerabilities, and to a lesser extent vulnerabilities associated with structural aspects of the financial system or the wider economy.

Developments in the indicators are mapped onto a common colour coding scheme, where a green (red) colour reflects low (high) levels of vulnerability. The heatmap signals vulnerabilities in three segments of the financial system:

- Commercial property prices have risen sharply over many years. The gap between actual price developments and trend has therefore been and remains positive and relatively wide.2

- Household debt service ratios (interest and estimated principal payments on loan debt to after-tax income) are high.

- Assets and lending associated with institutions other than banks and mortgage companies3 have shown strong growth. Mutual funds’ assets have risen in recent years, partly owing to increased subscriptions by insurance companies and pension funds. Insurance companies in particular have seen strong lending growth, though levels remain low. Vulnerabilities are therefore not considered to be elevated.

Composite indicators in the heatmap. 1980 Q1 – 2019 Q2

1 See Arbatli, E.C. and R.M. Johansen (2017) “A Heatmap for Monitoring Systemic Risk in Norway“, Staff Memo 10/2017, Norges Bank, for a detailed description of the heatmap and the individual indicators.

2 See Norges Bank´s website: “Indicators of financial imbalances” for an illustration of the gaps.

3 Financial institutions other than banks and mortgage companies comprise money market mutual funds, other mutual funds, finance companies, government lending institutions, insurance companies and pension funds.

Moderate house price inflation reduces housing market vulnerabilities

High house prices are a key financial system vulnerability in Norway. Sharp and sudden declines in house prices may trigger tightening of household consumption and result in increased losses on banks’ loan portfolios. The covered bond market may also be weakened. This may create bank funding shocks (see Section 2 Bank profitability, solvency and funding).

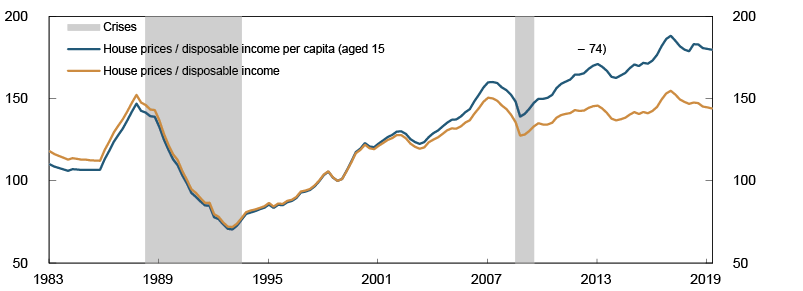

House prices have risen sharply over a long period and in nominal terms are at historically high levels. Over the past two years, the rise has been moderate, and house prices relative to household disposable income have moved lower (Chart 1.9). The cooling-off of the housing market has reduced the risk of a sudden and more pronounced price fall further out, and vulnerabilities have declined somewhat since the 2018 Report.

Chart 1.9 House prices relative to disposable income1 Index. 1998 Q4 = 100. 1983 Q1 – 2019 Q2

1) Disposable income is income after taxes and interest payments. Adjusted for a break in the series.

Sources: Eiendomsverdi, Finn.no, Norwegian Association of Real Estate Agents (NEF), Real Estate Norway, Statistics Norway and Norges Bank

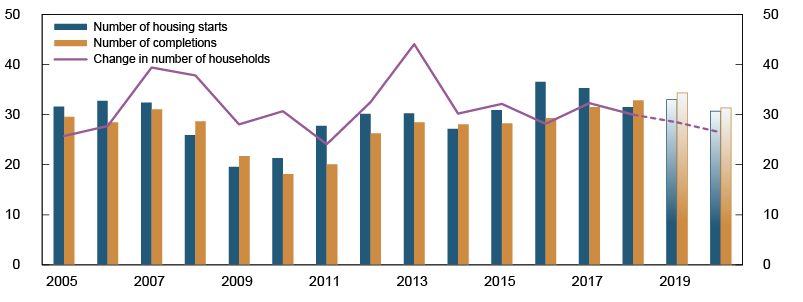

The recent moderate house price inflation may partly reflect increased residential construction.5 There was a record number of completions in 2018, and a new peak in the number of completions is expected in 2019 (Chart 1.10). Higher interest rates and the tightening of the regulation on new residential mortgage loans have also likely pulled down house price inflation.

Chart 1.10 Housing starts and completions, annual change in number of households In thousands. 2005 – 20201

1) Projections for 2019 and 2020.

Sources: Statistics Norway and Norges Bank

Moderate house price inflation is expected to continue ahead (see Monetary Policy Report 3/19). Higher interest rates and the large number of completions pull down the rise in house prices. Prospects for continued high demand for housing in urbanised areas and higher wage growth pull in the opposite direction. A more moderate rise in house prices may help restrain the build-up of household debt ahead.

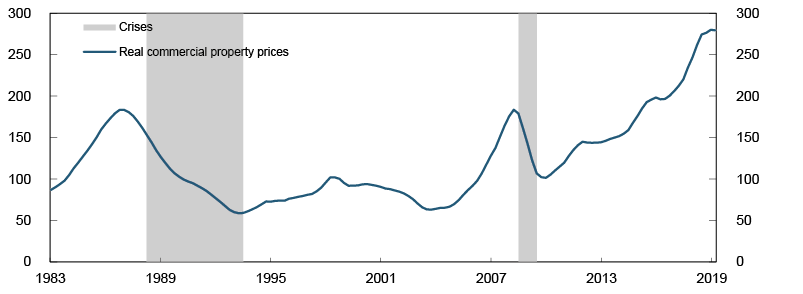

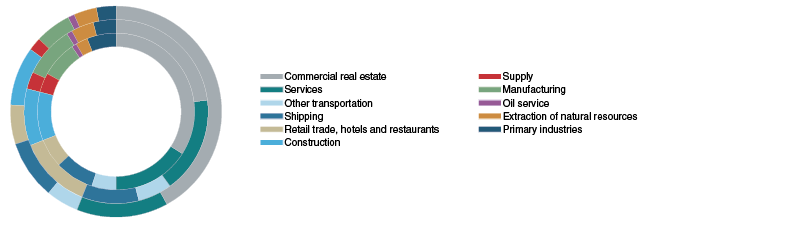

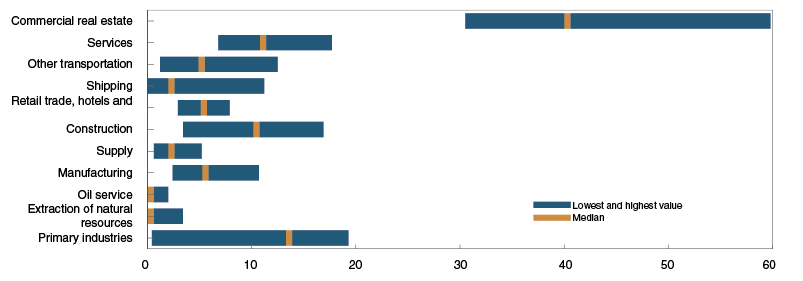

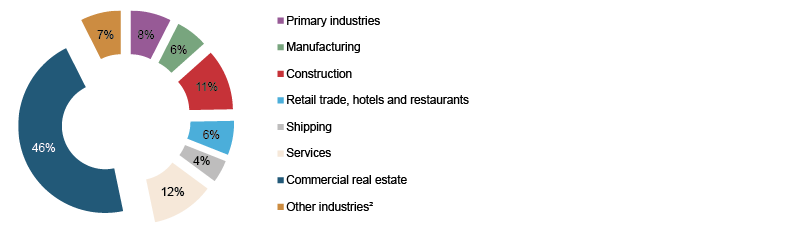

High commercial property prices

Vulnerabilities associated with high commercial property prices are broadly unchanged since the 2018 Report. In recent years, the rise in prices for commercial property in Oslo has been high, and real estate companies’ debt has risen. This has contributed to higher vulnerabilities for banks. Norwegian banks’ have sizeable exposures to commercial real estate (CRE) (see Section 3 Stress test). Even though in normal times, losses have been historically been low, CRE is the sector that has inflicted the most losses during crises.

Estimated real selling prices for prime office space in Oslo have been rising sharply over several years (Chart 1.11). Over the past year, the rise has been more moderate. Selling prices are estimated using rental prices and an estimated yield.

Chart 1.11 Real commercial property prices1 Index. 1998 = 100. 1983 Q1 – 2019 Q2

1) Estimated real selling prices per square metre for prime office space in Oslo. Deflated by the GDP deflator for mainland Norway. Average selling price for the previous four quarters.

Sources: CBRE, Dagens Næringsliv, OPAK, Statistics Norway and Norges Bank

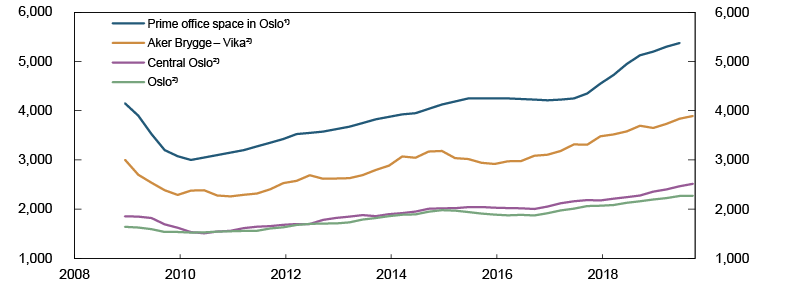

In isolation, rising rental prices strengthen the debt-servicing capacity of CRE companies. Rents for prime office space in central Oslo have risen sharply over the past few years (Chart 1.12). In other parts of Oslo, average rental prices have risen, but the rise has been lower than for prime office space. Norges Bank has developed a rental price index that takes into account that rent depends on the attractiveness of the office space (see "New rental price index for commercial real estate in Oslo"). This quality-adjusted index confirms that rents for the most attractive office space have risen more sharply in recent years than what could be considered representative for Oslo. According to Entra’s consensus report, market participants expect rents to continue to rise in Oslo, though at a slower pace than in 2019.

Chart 1.12 Office rents in Oslo. NOK per square metre per year Four-quarter moving average. 2008 Q4 – 2019 Q3

1) Market rents according to CBRE to 2019 Q2.

2) Calculated as the average rental price for signed leases, at lease signing date.

Sources: Arealstatistikk and CBRE

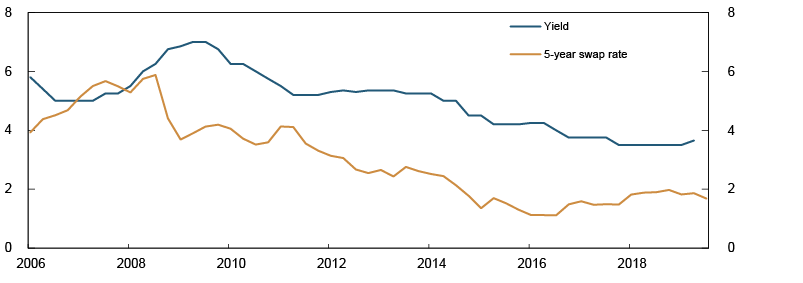

In line with falling interest rates, investors’ yields on CRE in Oslo fell over many years (Chart 1.13). In recent years, yields have been relatively stable. At the beginning of the year, market participants expected yields to gradually pick up in pace with the rise in long-term interest rates. When instead, long rates fell both abroad and in Norway, yield expectations also weakened somewhat. Market participants expect yields to remain broadly unchanged ahead.

Chart 1.13 Yield for prime office space in Oslo and long-term interest rates Percent. 2006 Q1 – 2019 Q31

1) Yield to 2019 Q2.

Sources: CBRE and Refinitiv

Overall, market participants’ expectations regarding rental price increases and yields suggest a further slight rise in selling prices in 2019 and 2020, but at a more moderate pace (see Monetary Policy Report 3/19).

Other important vulnerabilities

Digitalisation adds to vulnerabilities

Norway is at the forefront in the use of digital financial services. This makes the financial system vulnerable to unintended operational incidents and cyber attacks. The latter are becoming increasingly widespread and sophisticated. If the financial system lacks the capacity to absorb shocks, rectify faults and ensure continuity of important economic functions, this may result in economic costs that may weaken confidence in the financial system.

Examples from the non-financial sector serve to illustrate how digital vulnerabilities may give rise to substantial losses. So far, there have been no extensive disruptions in the financial system in Norway, and the data for estimating the cost of malicious attacks and operational incidents are therefore limited. This also makes it a challenge to assess both the level of and changes in digital vulnerabilities.

Extensive outsourcing has resulted in the concentration of ICT operation and development in the hands of a small number of service providers. This entails a concentration risk that is difficult to manage for the individual financial market infrastructure owner. A disruption among critical ICT service providers may affect important components of the payment system and other critical functions.

Climate risk also impacts the financial system

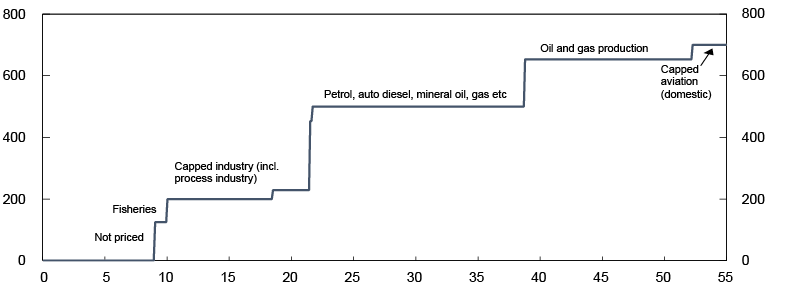

Climate change and society’s response to it may affect all parts of the economy and entail risks to financial stability. Climate risk is associated with both the physical consequences of climate change and the consequences of transitioning to a low-carbon economy. In Norway, the oil and gas industry will be the most relevant source of transition-related credit risk Norge. In recent years, Norwegian banks have reduced their oil sector exposures, but the oil industry is still important (see Section 4 Climate risk).

Large losses for the banking sector overall are not likely before a structural decline in oil-related activities results in significant spillovers to the wider economy. In addition, other industries currently subject to low or no carbon pricing may be at risk if carbon pricing or emissions standards are introduced or increased. Banks are particularly vulnerable if such spillover effects affect loans secured on real estate, which constitute the largest share of banks’ exposures.

3 The decline in lending growth in Finanstilsynet’s sample of consumer credit institutions would have been smaller if it had been corrected for the sale of portfolios of non-performing consumer debt.

4 See Financial Stability Report 2018, page 16, for a summary of measures aimed at the consumer credit market.

5 For a long time, residential construction activity was lower than warranted by the increase in the number of households in isolation. So that even though residential construction activity appears to be high now, it does not appear to be excessive (see Mæhlum, S., P.M. Pettersen and H. Xu (2018) “Residential construction and household formation”. Staff Memo 12/2018. Norges Bank.

1.3 Measures to mitigate vulnerabilities

Following the financial crisis, there has been broad international cooperation to increase financial system resilience. A range of measures have been introduced in Norway (see Table 1.1), with many others being formulated or amended.

Table 1.1 Important measures to mitigate financial system vulnerabilities in Norway

|

Category |

Instrument |

First introduced |

Current level |

|

Credit standards requirements for mortgages |

Tolerate higher interest rate (stress test)1 Loan-to-value (LTV) ratio Principal repayment requirement Debt-to-income (DTI)1 ratio Flexibility quota / “speed limit”2 |

20153 20153 20153 2017 2015 |

5 percentage points 85% (60% for loans secured on secondary homes in Oslo) 2.5% annually with LTV above 60% 5 times gross income 10% (8% or up to NOK 10m for loans secured on dwellings in Oslo) |

|

Credit standards requirements for consumer credit4 |

Tolerate higher interest rate (stress test)1 Principal repayment requirement Debt-to-income (DTI)1 ratio Flexibility quota / “speed limit”2 |

20193 20193 20193 2019 |

5 percentage points Monthly principal repayment, maximum term 5 years 5 times gross income 5% |

|

Weighted capital requirements5 (share of risk-weighted assets6) |

Pillar 1 Minimum CET1 requirement Pillar 1 Minimum Tier 1 requirement Pillar 1 Minimum regulatory capital Pillar 1 Combined buffer requirements: Capital conservation buffer Systemic risk buffer Buffer for systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) Countercyclical capital buffer Pillar 2 requirements |

2013 2013 2013 2013 2013 2015 2015 2016 |

4.5% 6% 8% 2.5% 3% 2% 2% Varies across banks |

|

Unweighted capital requirements5 (share of exposure measure) |

Leverage ratio |

2017 |

3% minimum requirement + 2% buffer requirement + 1% buffer requirement for systemically important banks |

|

Liquidity requirements |

Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) LCR in individual currencies LCR in NOK |

2015 2017 2017 |

100% 100% 50% (for banks with EUR/USD as significant currencies) |

|

Minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL)7 |

Loss absorption amount Amount necessary for recapitalisation8 |

2019 2019 |

Minimum requirement for regulatory capital + Pillar 2 requirements + combined buffer requirements Minimum requirement for regulatory capital + Pillar 2 requirements + combined buffer requirements excluding countercyclical capital buffer requirement |

1 The requirement pertains to the customer’s total debt.

2 Up to a certain percentage of the total value of new mortgage loans/consumer credit granted each quarter may be loans in breach of one or more of the requirements.

3 Prior to being laid down in a regulation, the requirements were issued as guidelines, for residential mortgage loans in 2010 and for consumer credit in 2017.

4 Exemption for credit cards with credit limits below NOK 25 000 and exemption for loan refinancing as long as the value of the refinanced loan (and associated costs) does not exceed the value of the existing loan (and associated costs).

5 See explanation of capital requirements in Norway’s Financial System 2019, pages 86–88.

6 A number of regulations have been introduced for banks’ calculation of risk weights, especially for residential mortgage loans.

7 Liabilities eligible for MREL must be lower in priority than senior debt. Equity capital used to meet the combined buffer requirement under Pillar 1 may not be used at the same time to meet MREL. This ensures that the buffers can function as intended.

8 Pertains only to banks subject to resolution and not liquidation under public administration.

Sources: Finanstilsynet and Ministry of Finance

Banks

Proposal to increase the systemic risk buffer

Some parts of the EU capital rules (CRR/CRD IV) have not been introduced in Norway, but are now set for inclusion in the EEA Agreement and Norwegian law. These rules will likely enter into force during 2019, and Norwegian and European rules will become more harmonised. The changes will allow banks to report higher capital ratios without raising solvency levels. In June, the Ministry of Finance circulated for comment proposed adjustments to the requirements, including increasing the systemic risk buffer from 3% to 4.5%. In its consultation response6, Norges Bank supported the increase (see Section 2 Bank profitability, solvency and funding).

Recovery and resolutions plans being finalised

On 1 January 2019, new bank recovery and resolution rules for Norwegian banks in line with the EU framework entered into force. These rules are intended to provide a solid framework for managing troubled banks. Finanstilsynet intends to finalise recovery and resolution plans for the nine most important Norwegian banks by year-end. The resolution and recovery plan for each bank will set minimum requirements for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL) (See Section 2 Bank profitability, solvency and funding).

Households

Proposal to tighten the regulation on residential mortgage loans

The regulation on requirements for new residential mortgage loans7 is intended to mitigate the risk of a substantial increase in debt among particularly vulnerable households. In September, the Ministry of Finance circulated for comment a proposal by Finanstilsynet to retain the regulation. Finanstilsynet recommends tightening the maximum debt-to-income (DTI) ratio (from 5 to 4.5) and the flexibility quota provision (from 10% to 5%), and repeal the Oslo-specific requirements. In its consultation response8, Norges Bank supported retaining the regulation, application for an indefinite period of time and nationally consistent requirements. In Norges Bank’s opinion, the maximum DTI requirement should not be changed.

Regulation on consumer credit introduced

The authorities have issued a new regulation on prudent standards for new consumer credit (Regulation on requirements for financial institutions’ consumer credit standards9), which entered into force in February 2019 and will remain in force until the end of 2020. The requirements in the consumer credit regulation largely echo the requirements in the regulation on requirements for new residential mortgage loans. A potential tightening of the maximum DTI in the latter regulation may therefore also have consequences for the former.

Credit registers have been established

The Debt Information Act is intended to improve the credit assessments of financial institutions that lend to retail customers and prevent debt problems from arising. From 1 July 2019, financial institutions are required on a daily basis to report debt information to credit registers on retail customers with unsecured debt.

Financial infrastructure

Strengthening cybersecurity10

To enhance cyber resilience and promote financial stability, the European Central Bank (ECB) the European framework for Threat Intelligence-based Ethical Red Teaming (TIBER-EU) for testing financial institutions’ detection, protection and response capabilities against sophisticated cyber attacks. Several neighbouring countries, including Denmark and Sweden, have introduced or are preparing to introduce TIBER-EU. Finanstilsynet and Norges Bank have invited the industry and relevant authorities to a dialogue to assess the suitability of introducing TIBER-EU in Norway.11

Over the past year, a number of international organisations have published further cyber security guidelines and frameworks. On 24 September 2019, the IMF published the report Cybersecurity Risk Supervision12. EU has introduced the EU Cybersecurity Act. Work is also ongoing at the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) to understand systemic cyber risk in the EU and assess whether cyber incidents may pose a financial stability threat. Norges Bank is participating in this work.

Follow-up of concentration risk, supervision and contingency arrangements

The ICT Security Commission, which presented its report in December 2018, has proposed measures to enhance the organisation and regulation of national ICT security.13 In its consultation response to the Ministry of Justice and Public Security, recommends further study of concentration risk, supervisory frameworks and contingency arrangements with a view to making specific proposals to address them (see Financial Infrastructure Report 2019).

Strengthening back-up arrangements for cash

Electronic contingency arrangements are the first line of defence in the event of a disruption in the payment system. Cash is a part of overall contingency preparedness. In 2018, the Ministry of Finance laid down a regulation14 to clarify banks’ obligation to supply cash in a contingency situation. For cash to function in a contingency, it must also be available and easy to use in a normal situation as well. Norges Bank is of the opinion that the current provision of cash services is not fully satisfactory and that a regulation governing the provision of cash services in a normal situation is needed.15

6 See Norges Banks høringssvar om tilpasninger i kapitalkravene for banker [Norges Banks consultation response on adjustments to banks’ capital requirements]. 30 September 2019 (in Norwegian only).

7 See Forskrift om krav til nye utlån med pant i bolig (boliglånsforskriften) [Regulation on requirements for new residential mortgage loans] (in Norwegian only)

8 See Norges Bank’s consultation response – Assessment of the regulation on requirements for new residential mortgage loans. 14 October 2019.

9 See Forskrift om krav til finansforetakenes utlånspraksis for forbrukslån [Regulation on requirements for financial institutions’ consumer credit standards] (In Norwegian only).

10 See Financial Infrastructure Report 2019, page 21.

11 See Norges Bank and Finanstilsynet (2019) “Norges Bank og Finanstilsynet ber om innspill til ev. innføring av rammeverk for testing av cybersikkerhet i Norge” [Norges Bank and Finanstilsynet request input on the possible introduction of cyber security testing framework in Norway]. Letter to the industry. 10 October 2019 (in Norwegian only).

12 See Gaidosch, T., F. Adelmann, A. Morozova and C. Wilson (2019) “Cybersecurity Risk Supervision”. Departmental Paper 19/15. IMF.

13 See Official Norwegian Reports (NOU) 2018:14. IKT-sikkerhet i alle ledd — Organisering og regulering av nasjonal IKT-sikkerhet [ICT security at every stage – Organisation and regulation of national ICT security] (ICT Security Commission) (in Norwegian only).

14 See Forskrift om endring i forskrift 9. desember 2016 nr. 1502 om finansforetak og finanskonsern.[Regulation to amend Regulation of 9 December 2016 No 1502 on financial institutions and financial groups] (in Norwegian only).

15 See Norges Bank (2019) “Bankenes tilbud av kontanttjenester – behov for regulering i forskrift” [Banks’ provision of cash services – need for a regulation]. Letter from Norges Bank to Finanstilsynet, 13 February 2019.

Higher share of highly leveraged households

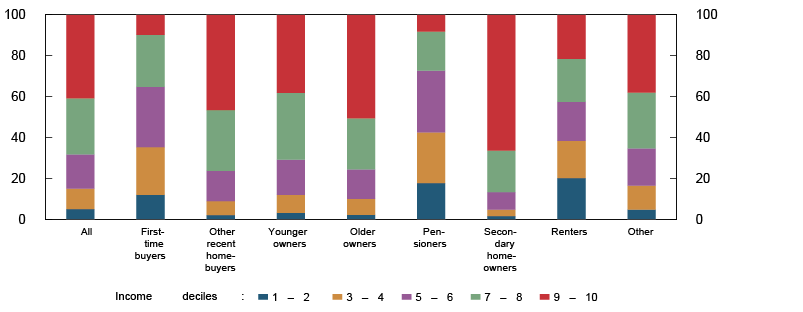

The share of households with debt exceeding five times gross income rose between 2016 and 2017. The debt-to-income (DTI) ratio for many first-time buyers was above five. Also in groups not active in the housing market there were households whose DTI rose to high levels, many of whom at the same time experienced a fall in income. Most debt is held by households in higher income deciles.

Debt accumulation is a function of homebuying

Household debt is closely linked to adjustments to the housing market. By combining household income and wealth data with data for home sales, we can study debt developments in various household groups. First-time buyers are generally more highly leveraged (higher debt relative to gross income) than other households (Chart 1.A). Other recent homebuyers are also highly leveraged. Among households who have not recently purchased a home, DTI ratios fall with age. The median pensioner and non-owner household holds little debt.

Chart 1.A Debt-to-income ratio1 By household group. 2016 and 2017

1) Debt as a share of gross income. Diamonds indicate the medians, bars the 25th to 75th percentiles and lines the 5th to 95th percentiles.

Sources: Ambita, Statistics Norway and Norges Bank

High-income households can be more highly leveraged than lower-income households and yet better able to make payments. In most household groups, most of the debt is held by households in higher income deciles (Chart 1.B). This is particularly evident among buy-to-let investors in secondary homes. The exceptions are first-time buyers, pensioners and renters. First-time buyers are young households that can generally expect higher income growth than older households.

Chart 1.B Debt by income decile. Share of total debt held by each household group Percent. 2017

Sources: Ambita, Statistics Norway and Norges Bank

Households that purchased a home in 2016 or 2017 account for close to 5% of all households and hold approximately 10% of total debt (Table 1.A). Homeowners who have not recently purchased a home in the past two years hold close to 80% of total debt. Renters and others, who account for nearly a third of households, hold the remaining 10%.

Table 1.A. Household groups.1 2017

|

Category |

Age |

Relationship with housing market |

Percent of all |

Percent of total debt |

|

First-time buyers |

20–34 |

Purchased in 2017. Not registered as owning in the two previous years. |

1.1 |

2.0 |

|

Recent homebuyers (excluding first-time buyers) |

20–90 |

Purchased in 2016 or 2017 and registered as owning in these years. |

3.1 |

7.5 |

|

Younger owners |

20–90 |

Registered as owning in 2016–2017, but did not purchase in these years. |

19.7 |

36.4 |

|

Older owners |

20–44 |

Registered as owning in 2016–2017, but did not purchase in these years. |

25.0 |

31.0 |

|

Pensioners |

45–64 |

Registered as owning in 2016–2017, but did not purchase in these years. Pension primary income source. |

16.2 |

5.7 |

|

Secondary homeowners |

65–90 |

Registered as a secondary homeowner and with rental income. |

2.5 |

6.2 |

|

Renters |

20–90 |

Not registered as owning in 2016–2017. |

27.5 |

7.2 |

|

Others |

20–90 |

4.9 |

4.1 |

1 Groups are mutually exclusive. Self-employed persons and some outliers have been omitted. The sample comprises 2.2m households in 2017.

Sources: Ambita, Statistics Norway and Norges Bank

DTIs rose between 2016 and 2017

Between 2016 and 2017, DTIs rose in all household groups except for renters. In this period, there was a rise in the share of households with a DTI above five and in the share of debt held by these households (Chart 1.C).

Chart 1.C Share of households with a DTI1 ratio higher than five and share of debt held by these households. Percent. 1987 – 2017

1) Debt as a share of gross income.

Sources: Statistics Norway and Norges Bank

The DTIs of around 2% of the households rose from below five in 2016 to above five in 2017 (Chart 1.D). Close to 40% of them are homeowners who are not recent homebuyers. For a large proportion of these homeowners, a fall in income pushed up their DTI. Among first-time buyers and other recent homebuyer households, a far smaller share experienced a fall in income at the same time as their DTI increased to above five.

Chart 1.D Households whose DTI1 rose to above five in 2017. Share of households in each household group. Percent

1) Debt as a share of gross income.

Sources: Ambita, Statistics Norway and Norges Bank

In 2017, a requirement for a maximum DTI of five was added to the regulation on new residential mortgage loans. Banks’ reporting to Finanstilsynet1 indicates that a substantial portion of the flexibility quota in the regulation is used for loans that breach the maximum DTI and that priority is given to young homebuyers. A number of banks have also stated they give priority to existing customers experiencing a change in circumstances, such as a divorce etc. This contributes to a larger proportion with a DTI above five among these household groups. According to calculations using the combined data from Statistics Norway and Ambita, a good 25% of first-time buyers took on debt corresponding to a DTI above five in 2017.

1 See Finanstilsynet’s consultation response on the regulation on new residential mortgage loans, 10 September 2019 (in Norwegian only).

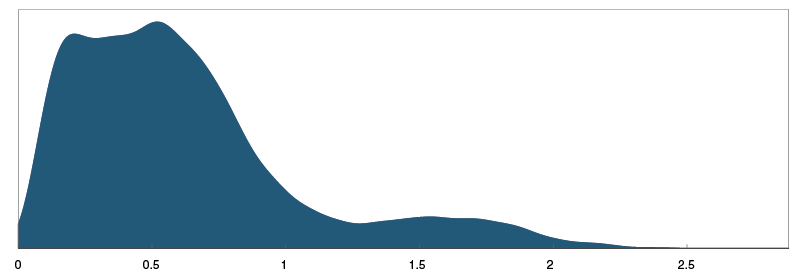

Credit register data show uneven distribution of consumer debt

Credit register data show that around a quarter of the population had consumer debt in one form or another at the end of September 2019. Consumer debt is unevenly distributed. Most consumer loans are small, but for a small minority, consumer debt was very large.

From 1 July 2019, financial institutions must report unsecured personal loans to the credit registers. The credit registers provide details on an individual’s unsecured debt. The registers record all debts not secured by a registered security interest. Credit registers enable financial institutions to make a more accurate assessment of a borrower’s creditworthiness, and give borrows easier access to details regarding their own debts. The authorities also obtain a more granular overview of the overall vulnerabilities and risks associated with unsecured debt in Norway.

To distinguish consumer debt from other unsecured debt1 “consumer debt” is restricted here to debt carrying an interest rate above 8%. Consumer debt consists of instalment loans with a contractual repayment period and credit card debt. Credit card holders can draw on a line of credit up to an agreed limit without needing creditor approval. Amounts drawn are often interest-free until after a grace period. At the end of September, the average credit card holder had drawn on around 30% of the total credit line available. Approximately 30% of the amount drawn was interest-free. Interest-free balances are assumed to be payment transactions and are not a part of consumer debt.

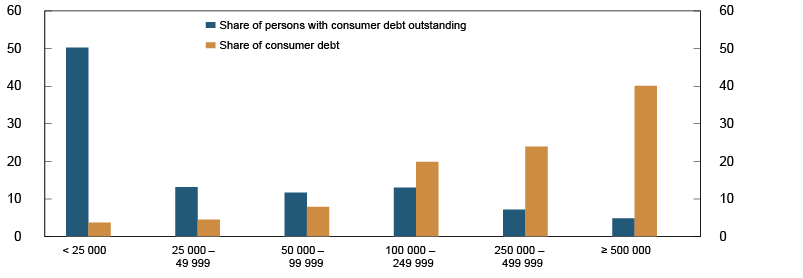

Many have consumer debt – just a few owe very large amounts

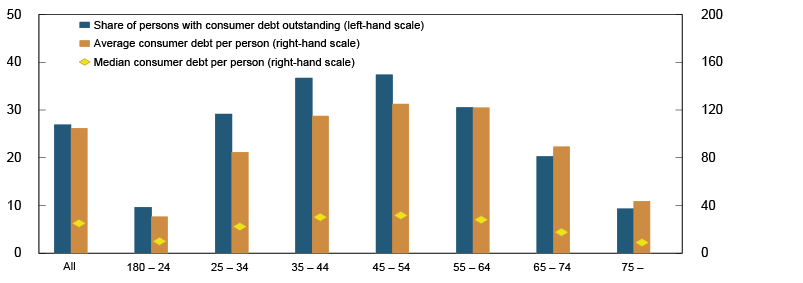

In principle, access to consumer credit is a good that gives households financial flexibility. According to the credit register, consumer debt outstanding accounted for around 3.5% of total domestic household debt at the end of September. A good quarter of the population over age 18 had interest-bearing consumer debt. Among the youngest and oldest age cohorts, there are far fewer with consumer debt (Chart 1.E).

Chart 1.E Persons with consumer debt outstanding as a share of the population Percent. Consumer debt per person. In thousands of NOK. By age. At 30 September 2019

Sources: Gjeldsregisteret AS and Norges Bank

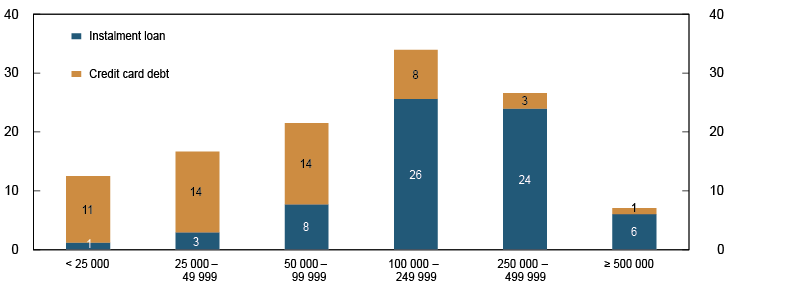

Consumer debt is unevenly distributed. Half of borrowers had consumer debt balances of NOK 25 000 or less, but all together they held below 5% of total consumer debt (Chart 1.F). Nearly all balances below NOK 25 000 comprise credit card debt (Chart 1.G). A quarter of borrowers had balances of between NOK 25 000 and NOK 100 000. This debt is also predominantly credit card balances. The last quarter had balances of above NOK 100 000, primarily in the form of instalment loans. Instalment loans account for around 60% of total consumer debt.

Chart 1.F Distribution of persons with consumer debt outstanding and consumer debt balances held by these persons By amount of consumer debt in NOK. Percent. At 30 September 2019

Sources: Gjeldsregisteret AS and Norges Bank

Chart 1.G Consumer credit By credit type and unpaid balances in NOK. In billions of NOK. At 30 September 2019

Sources: Gjeldsregisteret AS and Norges Bank

Low-value debt carries high interest rates and is repaid quickly

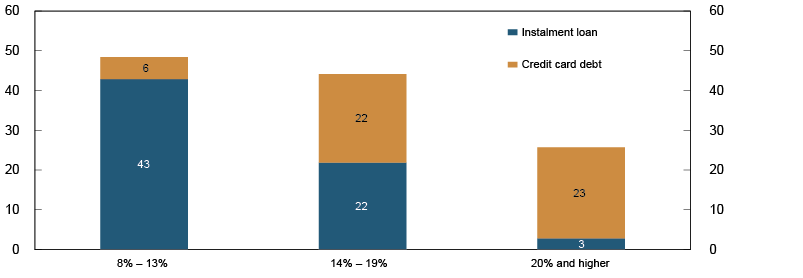

Consumer loans that are repaid after a short period have a limited total cost. Nevertheless, if the loan balance is large relative to income, covering interest expenses may be difficult. Once a borrower runs into repayment difficulties, interest compounding can quickly magnify the problem. Interest rates above 8% are high compared with a typical residential mortgage rate of around 3%. A considerable share of loan balances outstanding carried an interest rate far higher than 8% (Chart 1.H).

Chart 1.H Consumer credit By credit type and interest rate. In billions of NOK. At 30 September 2019

Sources: Gjeldsregisteret AS and Norges Bank

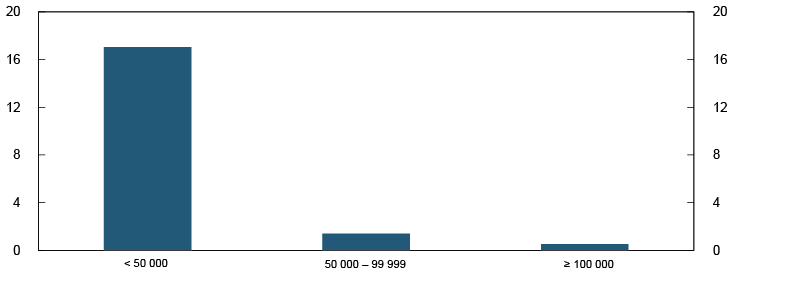

Nearly 20% of those with loan or credit card balances under NOK 50 000 at the beginning of September had repaid them by the beginning of October (Chart 1.I). For those with loan balances above NOK 100 000, under 1% had repaid the entire balance in the following month.

Chart 1.I Persons who had repaid their entire consumer debt balances by the beginning of October 2019 By amount of debt in NOK. Percentage of those with consumer debt balances at the beginning of September 2019

Sources: Gjeldsregisteret AS and Norges Bank

Consumer credit banks extend the most credit

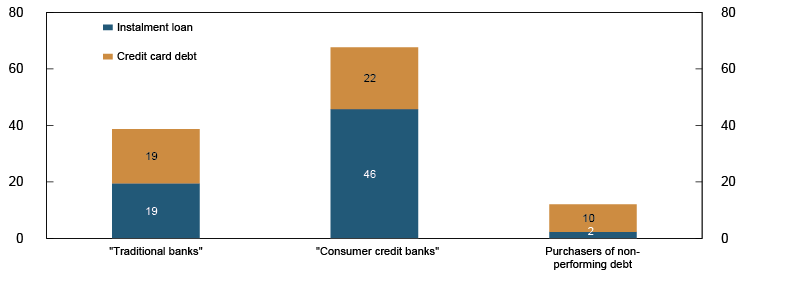

Financial institutions that specialise in consumer financing – “consumer credit banks” – accounted for over half of total consumer credit at the end of September (Chart 1.J). Financial institutions where consumer financing is only one of several products – “traditional banks” – accounted for around one-third of consumer credit. Consumer credit banks and traditional banks both sell portions of their non-performing credit card and loan portfolios to finance companies that specialise in purchasing non-performing debt. Such finance companies held 10% of total consumer debt.

Chart 1.J Consumer credit By credit and lender type. In billions of NOK. At 30 September 2019

Sources: Gjeldsregisteret AS and Norges Bank

1 The data have been obtained from Gjeldsregisteret AS. Not all unsecured debt is consumer debt. For example, banks provide bridge financing in connection with home purchases as an unsecured loan at a relatively low interest rate under the assumption that collateral will be pledged within a short time. Many of the largest loans in the credit register carry an interest rate of below 5%.

New rental price index for commercial real estate in Oslo

Norges Bank has long used selling prices for prime office space in Oslo as an important indicator of developments in financial imbalances. However, limited availability of data has made it difficult to assess whether price developments in this segment are representative of the overall commercial real estate market. On the basis of an enlarged dataset, the Bank has developed a quality-adjusted rental price index that indicates a higher rise in rental prices for prime office space in the recent period than for the office space market in Oslo as a whole.

The commercial real estate (CRE) market is important for financial stability. However, available data are limited and of varying quality. Norges Bank therefore uses several sources to obtain the best possible overview of developments in the sector. Important market indicators are yield, rental and selling prices. Selling prices for prime office space in Oslo is regarded to be a particularly important indicator of CRE market vulnerabilities, because these prices have historically risen sharply ahead of financial crises. Selling prices are estimated as rental prices divided by yield. The yield for prime office space in Oslo is often used as a benchmark for pricing other office space. Even though prime office space in Oslo is an important segment, it will not necessarily provide a representative picture of sector developments.

A new quality-adjusted index shows differences in rental price developments

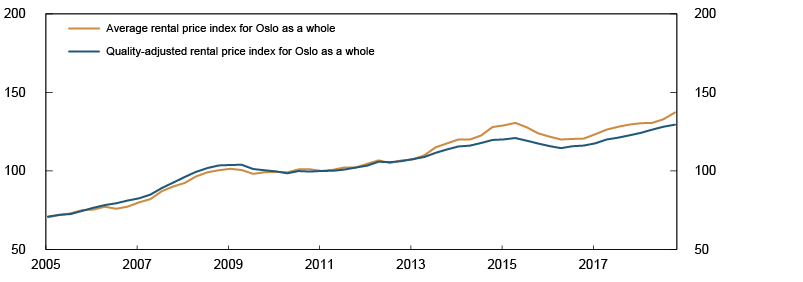

In its work to improve the basis for its CRE sector analyses, the Bank has developed quality-adjusted rental indexes for office space in Oslo. The indexes are calculated with the aid of rental price data based on actual leases that cover a large part of the office market in Oslo.1 Quality-adjusted indexes result in more comparable rental prices than indexes based on average rents.2 Average rents are affected by whether a relative large number of leases have been signed for attractively located or high-quality office space, for example. Differences in such attributes should not influence a rental price index, and the quality-adjusted index takes this into account. For Oslo as a whole, the quality-adjusted index shows a somewhat more pronounced rise prior to the financial crisis and weaker price developments in the period 2013 to 2015 than developments in the average (Chart 1.K).

Chart 1.K Office rents in Oslo.1 Four-quarter moving average. Index. 2011 Q1 = 100. 2005 Q1 – 2018 Q4

1) Based on signed leases, at lease inception date.

Sources: Arealstatistikk and Norges Bank

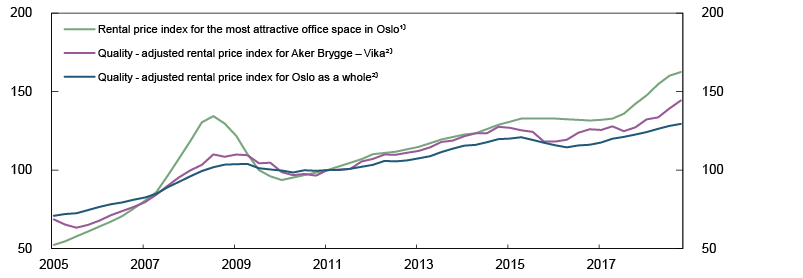

To assess whether developments in the established rental price index for prime office space in Oslo are representative, they were compared with the quality-adjusted rental indexes for Oslo and for Aker Brygge-Vika (Chart 1.L). The Aker Brygge-Vika index covers broadly the same geographical area as the established index but also includes less attractive office space. All indexes have moved in the same direction since 2005. However, the established index fluctuated more around the time of the financial crisis and has recently shown a sharper rise than both quality-adjusted indexes.

Chart 1.L Office rents in Oslo.1 Four-quarter moving average. Index. 2011 Q1 = 100. 2005 Q1 – 2018 Q4

1) Market rents according to CBRE. 2) Based on signed leases, at lease inception date.

Sources: Arealstatistikk, CBRE and Norges Bank

1 The data are collected by the company Arealstatistikk.

2 See Anundsen, A. and M. Hagen (2019): “Hedonic indices for rental prices in the Oslo office market” Forthcoming Working Paper. Norges Bank. The index is hedonic, which means that rental prices depend on a number of attributes that must be controlled in order to make these prices comparable. The rental price index is calculated as the relationship between two equally attractive offices at time t compared with the base year.

Should a CBDC be introduced in response to changes in the payment system?

New regulations, new operators and new technologies will transform the payment system ahead. At the same time, cash usage is falling. Norges Bank is considering whether introducing a central bank digital currency may be desirable.

Access by the public to central bank money is a key feature of the payment system. This access is currently provided for by cash. But at some point, cash usage may become so low that despite its status as legal tender, cash may no longer be considered a generally available means of payment. To ensure a secure and efficient payment system and confidence in the monetary system also in the future, Norges Bank is analysing the feasibility of introducing a central bank digital currency (CBDC). In summer 2019, a Norges Bank working group published its second report on CBDCs1.

Deposit money is a secure means of payment, but a CBDC may be a good back-up solution and promote competition

In its second report, the working group concluded that introduction of a CBDC does not seem necessary to ensure the public access to a secure means of payment. The regulatory framework for the financial system already provides for this, and the deposit money created by banks is a secure means of payment. Within the deposit guarantee, there is no credit risk.

The working group believes that the contingency preparedness aspect may be an argument for introducing a CBDC. A CBDC can secure technical autonomy from ordinary payment systems and sufficient national control. A CBDC can also offer competition with private payment solutions in a situation where competition proves weak. Finally, a CBDC can be useful for ensuring access to legal tender in the Norwegian financial system. The payment system and means of payment may evolve in a different direction or at a different pace than can be currently foreseen. A precautionary approach may warrant practical preparations in order to keep open the possibility of introducing a CBDC.

A possible design of a CBDC is now being studied

On the condition that deposit money will continue to be a substantial part of bank financing, also if a CBDC is introduced in Norway, the working group is considering two different models for a CBDC.

- One model is a “register-based” solution. Unlike deposit money, control over register-based “tokens” is not based on an account linked to a personal identity. Funds may be used by the party in possession of an access code. This solution will also need to facilitate compliance with anti-money laundering rules.

- An alternative is a “closed account” solution. In it, both payer and payee must have a CBDC account. The CBDC may then be regarded as e-money issued by a public entity (and not by an e-money institution like PayPal).

The working group is considering both models with respect to fitness for purpose and to possible undesired consequences for financial stability.

The ongoing study of the design of a CBDC is part of a long-term effort, and Norges Bank will monitor international thinking in this area. More information is needed before a conclusion can be drawn that introducing a CBDC is a desirable measure for promoting a secure and efficient payment system and continued confidence in the monetary system. Norges Bank will continue to issue cash as long as it is appropriate.

1 See Norges Bank (2019) “Central bank digital currencies” Norges Bank Papers 2/2019.

2 Bank profitability, solvency and funding

For Norwegian banks, credit losses are low and profitability is solid. Sustained profitability is expected in the coming years. Downside risks are higher losses and reduced margins owing to increased competition between banks and from new entrants.

Banks are solid and fulfil the capital requirements. The remaining parts of the EU capital framework will likely be implemented soon in Norway. Norwegian and European rules will then become more harmonised.

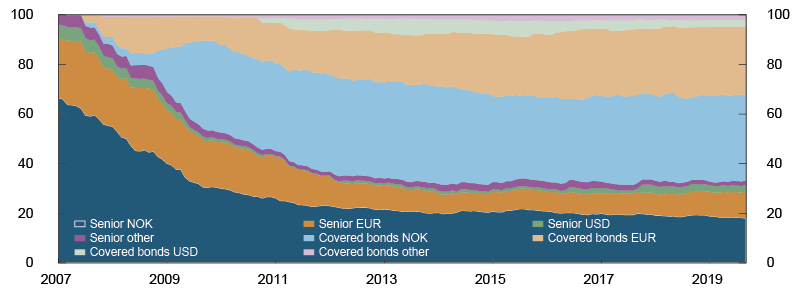

Norwegian banks have ample access to funding. They satisfy liquidity requirements and their vulnerability to a dry-up of short-term foreign currency funding is reduced. Finanstilsynet (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway) aims to set resolution plans and requirements for own funds and eligible liabilities for the nine most important Norwegian banks by year-end 2019. In Norway, future regulations may permit securitisation, which is a new funding source for lending.

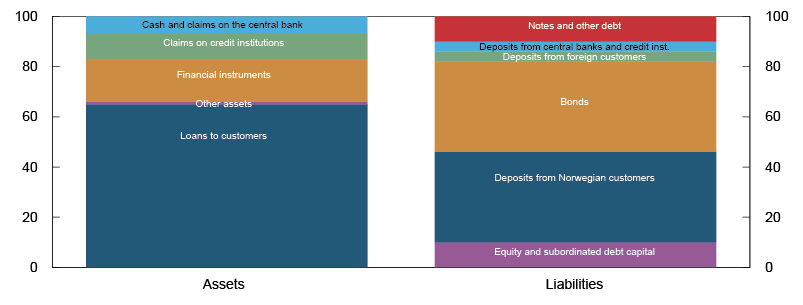

Banks play a key role in the economy and perform important tasks such as channelling funds, executing payments and distributing risk efficiently. Banks’ ability to absorb credit losses depends on underlying profitability and solvency. Robust liquidity is also important in order for banks to carry out their tasks well, even during periods of funding market stress.

2.1 Profitability

Continued solid profitability among Norwegian banks

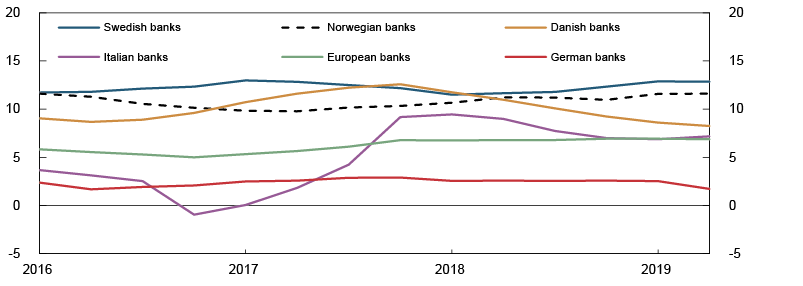

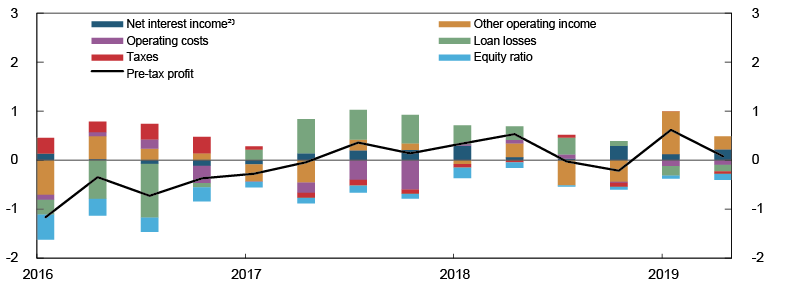

The large Norwegian banks have maintained their profitability over the past year and are, together with Swedish banks, at a high level compared with other European banks (Chart 2.1).

Chart 2.1 Return on equity after tax. Large Norwegian banking groups1 and European2 banks Four-quarter moving weighted average. Percent. 2016 Q1 – 2019 Q2

1) Weighted average of DNB Bank, Nordea Bank Norge (to 2016 Q4), SpareBank 1 SR-Bank, Sparebanken Vest, SpareBank 1 SMN, Sparebanken Sør (from 2016 Q1), SpareBank 1 Østlandet (from 2016 Q3) and SpareBank 1 Nord-Norge. Consolidated figures.

2) Based on a sample of 150 European banks. The sample varies over time.

Sources: European Banking Authority (EBA), Norwegian banking groups' quarterly and annual reports and Norges Bank

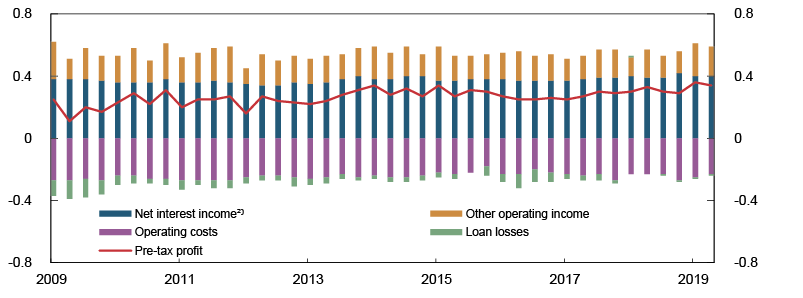

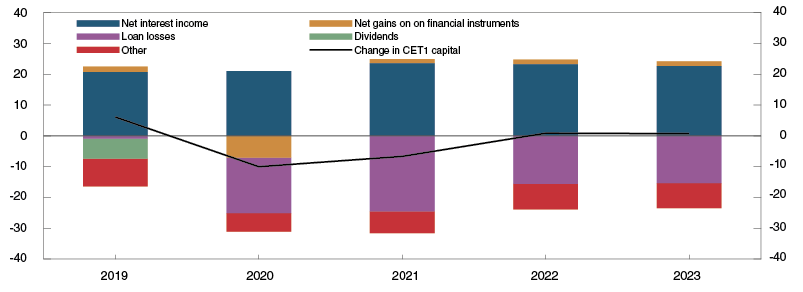

Stable net interest income and low credit losses have enabled Norwegian banks to maintain profitability (Chart 2.2). Banks’ primary revenue source is net interest income from traditional banking. The increase in net interest income improved the profitability of the largest Norwegian banks in 2017, 2018 and in the first half of 2019 (Chart 2.3). Lending rates have risen more than deposit rates, resulting in higher interest margins in recent quarters.

Chart 2.2 Decomposed change in profits. Large Norwegian banking groups1 As a percentage of average total assets. 2009 Q1 – 2019 Q2

1) Weighted average of DNB Bank, Nordea Bank Norge (to 2016 Q4),

SpareBank 1 SR-Bank, Sparebanken Vest, SpareBank 1 SMN, Sparebanken Sør (from 2014 Q1), SpareBank 1 Østlandet (from 2016 Q3) and SpareBank 1 Nord-Norge.

2) Commission income from part–owned mortgage companies in the SpareBank 1–alliance has been reclassified from other operating income to net interest income.

Sources: Bank's quarterly reports and Norges Bank

Chart 2.3 Estimated contributions to changes in large Norwegian banking groups'1 return on equity after tax Four-quarter moving weighted average of annualised return. Percentage points. 2016 Q1 – 2019 Q2

1) Weighted average of DNB Bank, Nordea Bank Norge (to 2016 Q4), Sparebank 1 SR-Bank, Sparebanken Vest, Sparbanken Vest, SpareBank 1 SMN, Sparebanken Sør (from 2014 Q1), SpareBank 1 Østlandet (from 2016 Q3) and SpareBank 1 Nord-Norge.

2) Commission income from part–owned mortgage companies in the SpareBank 1–alliance has been reclassified from other operating income to net interest income.

Sources: Banks' quarterly reports and Norges Bank

Profitability expected to be maintained

Mainland GDP is expected to slow somewhat in the coming years (see Monetary Policy Report 3/19). Bank analysts’ average projection of the largest banking groups’ profitability for the coming years is at broadly the same level as in recent years (Chart 2.4). Norges Bank’s bankruptcy probability model1 indicates that banks’ credit risk on loans to non-financial enterprises will be fairly stable in 2019 and increase slightly in 2020. With prospects for continued low credit losses and the absence of major economic shocks, banks as a whole are therefore expected to maintain solid profitability in the coming years.

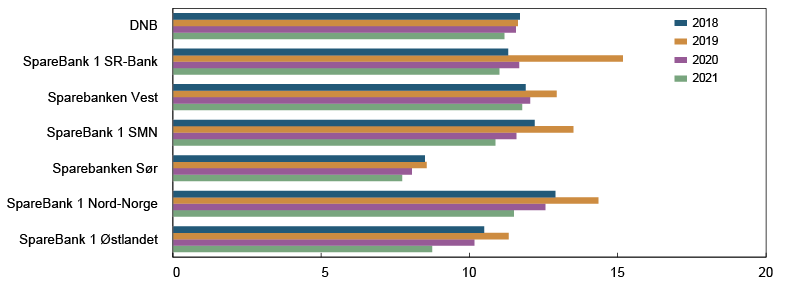

Chart 2.4 Analysts' estimates of return on equity in large Norwegian banking groups1 Percent. At 31 October 2019

1) As reported in banks' annual reports in 2018. The high profitability in 2019 reflects extraordinary revenues.

Sources: Banks' annual reports and Bloomberg

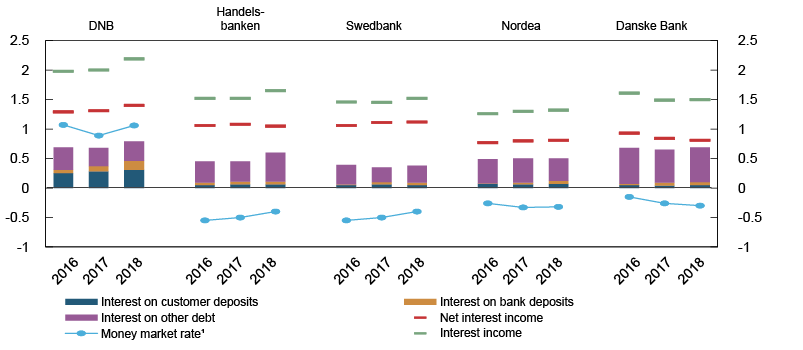

European banks’ profitability under pressure from negative interest rates

The profitability of large Danish banks has weakened in recent quarters (Chart 2.1), owing in part to the low interest rate level. Swedish, Danish and euro area money market rates have been negative since 2015. Banks are reluctant to offer negative deposit rates as depositors have the option of withdrawing their deposits in cash rather than pay a negative deposit rate. In spite of negative money market rates, average Swedish and Danish deposit rates are not negative.

Since banks’ wholesale funding includes a risk premium on top of the money market rate, the interest rate on wholesale funding can be positive even when the money market rate is negative. With deposit rates close to zero, wholesale funding costs will account for most of banks’ total interest expenses. This was the case for Handelsbanken, Swedbank, Danske Bank and Nordea in the period 2016–2018 (Chart 2.5). Deposit rates in Norway are positive, and for DNB deposit costs account for a large share of interest expenses. With a deposit rate close to zero, a further reduction in the interest rate level will likely merely reduce the cost of wholesale funding.

Chart 2.5 Large Nordic banking groups' interest expenses, interest income and net interest income As a percentage of total assets. 2016–2018

1) 3-month Nibor, Stibor, Cibor and Euribor.

Sources: SNL / S&P MI, Refinitiv and Danske Bank's annual report

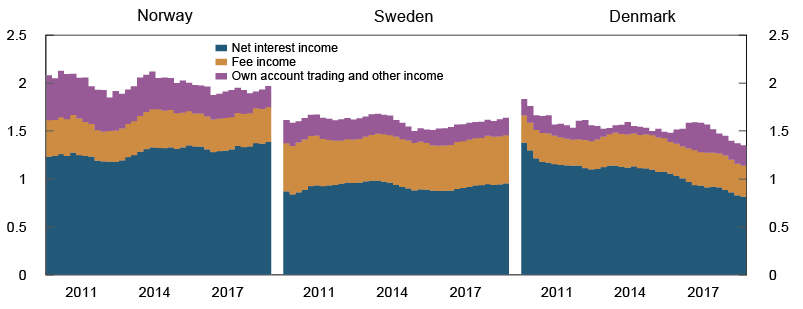

Reduced operating costs or increased revenue may compensate for the cost disadvantage of a limited pass-through to deposit rates when the money market rate is negative. Revenue can primarily be increased through higher lending growth, higher fees and higher lending margins. Banks in Sweden have kept their lending rates elevated, which has contributed to sustaining the level of net interest income (Chart 2.6). In Denmark, the low level of interest rates and falling interest margins have resulted in lower net interest income.2 Fee income has been relatively stable in Norway, Sweden and Denmark.

Chart 2.6 Operating income for selected banking groups in Norway, Sweden and Denmark1 As a percentage of total assets. 2010 Q2 – 2019 Q2

1) Norwegian banks: DNB, SpareBank 1 SR-Bank, SpareBank 1 SMN, SpareBank 1 Nord-Norge and Sparebanken Vest. Swedish banks: Handelsbanken, SEB and Swedbank. Danish banks: Danske Bank, Jyske Bank, Spar Nord Bank and Sydbank.

Source: SNL / S&P MI and Norges Bank

If interest rates remain very low or negative over a long period, structural changes may result in the financial system, which could also impact banks.3 Over time, depositors may opt for higher-risk investments, such as mutual funds, rather than keep their money in a bank at zero interest. Low interest rates over an extended period may also fuel a credit-driven rise in prices for assets such as equities and real estate. Low interest rates also make it difficult for pension and insurance companies to meet the rate-of-return guarantees for their pension products.

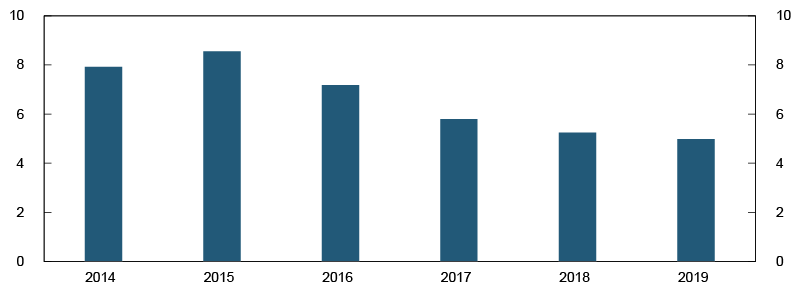

Risk of increased losses

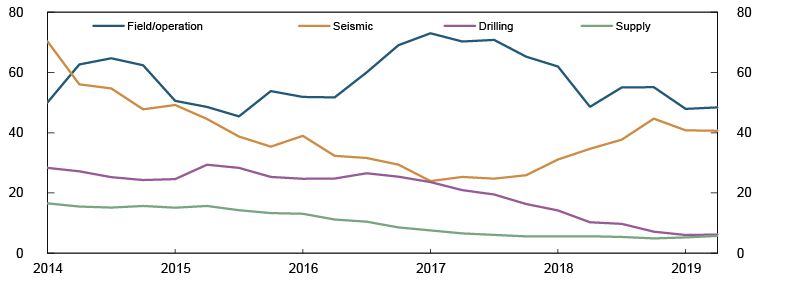

Some uncertainty still remains about the need for further restructuring in oil-related enterprises. Such restructuring has inflicted losses on banks in recent years. The losses proved to be somewhat lower than initially expected following the fall in oil prices in 2014, and spillovers to other sectors have been more modest than assumed. Persistent overcapacity in segments of the oil service industry may lead to further restructuring accompanied by losses, since the debt-servicing capacity of many oil service companies has weakened in recent years (Chart 2.7). Banks’ direct oil-related exposures are nevertheless limited and account for less than 5% of total exposures (see "Banks and the experience gained from the downturn in the oil industry").

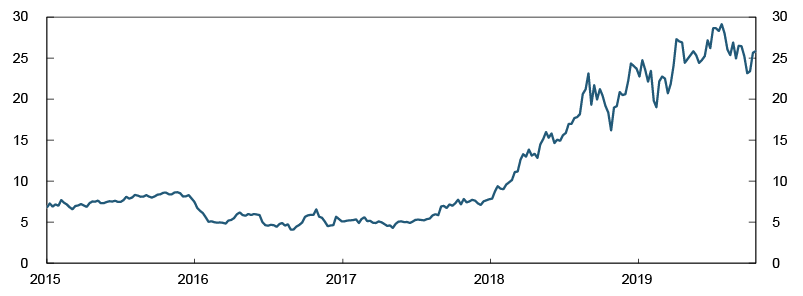

Chart 2.7 Debt-servicing capacity1 in the oil service industry Percent. 2014 Q1 – 2019 Q2

1) Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) for the last four quarters as a percentage of net interest-bearing debt. The EBITDA measure has been standardised by Bloomberg. Manual adjustments for EBITDA have been made where erroneous registrations appear in Bloomberg's measure.

Sources: Bloomberg, company quarterly and annual reports and Norges Bank

A substantial share of banks’ exposures is to commercial real estate (CRE) (Chart 3.8). Commercial property prices are at a high level (Chart 1.11). The rise in prices has often been strong prior to a substantial fall. Even though losses have historically been low in normal times, CRE is the sector where banks have historically incurred the larges losses during crises. The stress test in Section 3 shows banks’ vulnerability to CRE losses in the event of a pronounced downturn in the Norwegian economy.

Prospects for increased competition

Technological and regulatory developments are allowing the competitive landscape to change with the entry of new service providers in areas that are important for banks’ profitability.

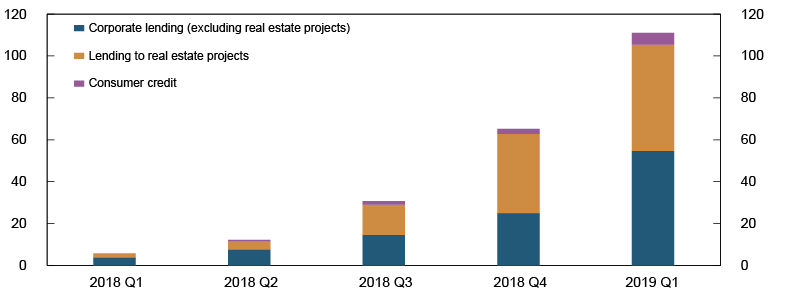

Crowdfunding, or extending credit through digital platforms, is an example of how new participants can impact competition in the credit market. The extent of crowdfunding so far has been very limited and had no impact on banks’ profitability in Norway. In spring 2019, Norges Bank conducted a survey of all active participants engaged in debt- and equity-based crowdfunding in Norway.4 Debt-based crowdfunding accounts for the largest share of financial crowdfunding.5 Total lending in the period between 2018 Q1 and 2019 Q1 amounted to approximately NOK 110m (Chart 2.8). Lending to real estate projects and enterprises account for the largest share of lending. The share of consumer credit was approximately 5% and is growing.

Chart 2.8 Cumulative lending by crowdfunding companies by sector. In millions of NOK 2018 Q1 – 2019 Q1

Source: Norges Bank

The revised Payment Services Directive (PSD2) entered into force in Norway on 1 April 2019.6 PSD2 may provide customers with improved and less expensive banking services. The Directive permits third-party providers (TPPs) to offer account information services (AIS) and execute payments on behalf of banks’ customers. The TPPs are either new entrants or banks that already operate in the market. This may promote new services that facilitate comparison shopping for banking services. For example, a number of banks have upgraded their online banking platforms to enable customers to view multi-bank account details under a single portal.

By improving market transparency, PSD2 may promote competition in banking services and put pressure on banks’ interest margins and fee income. The effects of PSD2 on banks’ income will depend on how they adapt. Banks may strengthen customer loyalty by changing their services so that they are less vulnerable to increased competition. An example of this is customer dividends, which savings banks, for example, distribute to customers on the basis of amounts borrowed or on deposit over the preceding year. Banks may also offer customers benefits for purchasing services with lock-in periods or for purchasing bundled products.

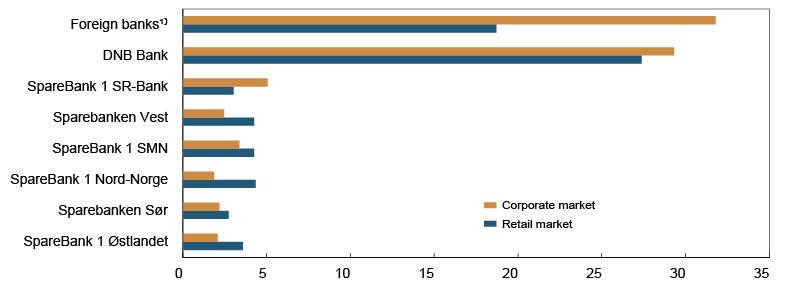

If profitability in the Norwegian banking market continues to be higher than what foreign banks are able to attain in their domestic markets, foreign banks may want to increase their activity in the Norwegian market. Increased competition from foreign banks may put pressure on interest margins and reduce profitability in the Norwegian banking market. Foreign-owned banks and foreign branches already have a substantial share of both the retail and corporate lending markets (Chart 2.9).

Chart 2.9 Market shares measured by gross lending Large banking groups in Norway. Percent. At 31 December 2018

1) Nordea, Danske Bank and Handelsbanken.

Source: Norges Bank

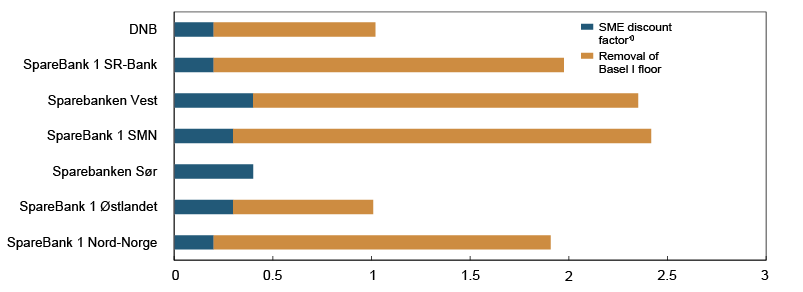

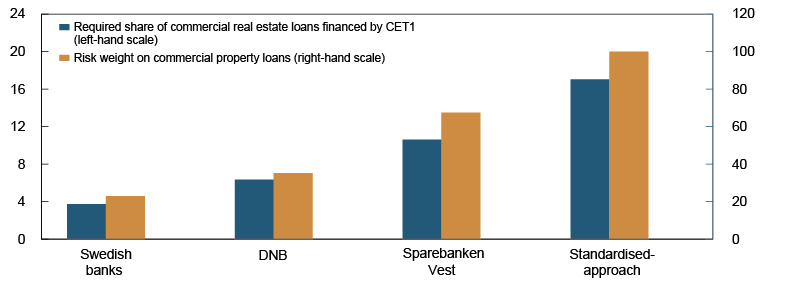

Material differences in risk weights for commercial real estate exposures

The risk weights that banks use for their commercial real estate (CRE) exposures range from 100% for standardised approach banks to a 23% average risk weight for large Swedish banks1. Norwegian IRB banks fall in between. Risk weights affect the amount of capital banks must hold. The share of CRE loans that a bank must finance using Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital is estimated by multiplying the bank’s CET1 capital requirement with its average risk weight for CRE exposures and then put on an add-on for operational risk. The calculated share varies between 4% for large Swedish banks and 17% for the Norwegian standardised approach banks (Chart 2.13).2

The considerable variation in risk weights for CRE exposures may have a number of explanations. One might be different portfolio compositions across banks. The market for lending to CRE companies is heterogeneous, and credit risk on these exposures can vary considerably. Some banks’ borrowers have lower credit risk, and therefore their CRE exposures have lower risk weights than those of other banks. Another possible explanation for the variation is that banks employ different methods and risk models. This may result in different risk weights for comparable exposures.

The authorities in a number of European countries have introduced minimum risk weight requirements. According to a preliminary assessment by the Swedish supervisory authority, the average risk weight for CRE exposures should be increased to a minimum of 30%. The Ministry of Finance’s proposed 35% minimum risk weight requirement for Norwegian CRE exposures is at or below the average risk weight of Norwegian IRB banks.

1 See Finansinspektionen (2019), “Stability in the Financial System (2019:1)”.

2 For a further description of the calculations, see Andersen, H. (2019) “How much capital must banks set aside for CRE exposures?” (forthcoming in English). Staff Memo [10/2019]. Norges Bank. In this Memo, capital requirements are assessed against CRE losses during the banking crisis.

1 The model is described in Hjelseth, I.N. and A. Raknerud (2016), “A model of credit risk in the corporate sector based on bankruptcy prediction”, Staff Memo 20/2016, Norges Bank. The model primarily covers industries in mainland Norway.

2 See Danmarks Nationalbank (2019) Financial Stability – 1st half 2019, page 7.

3 The consequences of very low and negative interest rates are also discussed in Section 6 of Financial Stability Report 2016 and in European Systemic Risk Board (2016) “Macroprudential policy issues arising from low interest rates and structural changes in the EU financial system”.

4 See Bankplassen blog, Fahre, B. and Y. Søvik “Folkefinansiering vokser i Norge – hvordan kan norske myndigheter være forberedt?” [Crowdfunding is growing in Norway – How can the Norwegian authorities be prepared?] (in Norwegian only).

5 In the equity-based crowdfunding segment, the data are too limited to show any clear trends in recent years.

6 See the 2019 Financial Infrastructure Report for a further description of PSD2.

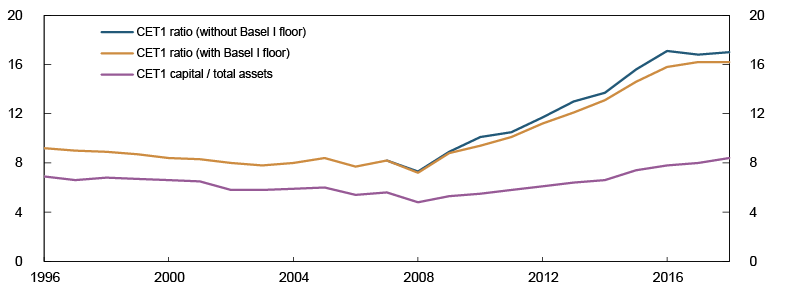

2.2 Solvency

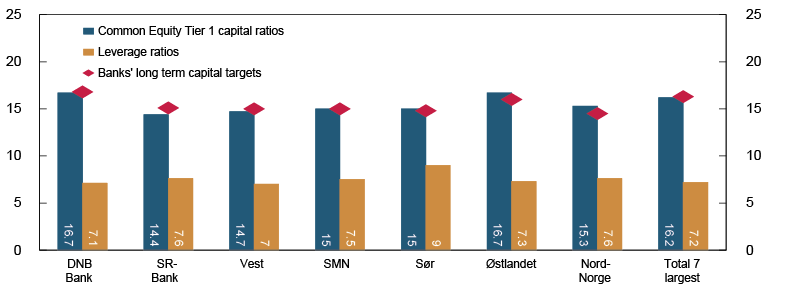

Banks have increased their Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratios since the financial crisis in 2008 (Chart 2.10), primarily by retaining earnings. In 2018, banks’ capital ratios were broadly unchanged, even though their profitability was solid. The dividend payout ratios for most of the large banks were, with few exceptions, unchanged in 2018 compared with 2017. Increased lending, including corporate lending, resulted in an increase in risk-weighted assets and kept capital ratios unchanged. Nevertheless, all Norwegian banks fulfil the capital requirements. The large banks’ CET1 capital ratios are near their long-term capital targets (Chart 2.11). The stress test shows that Norwegian banks have sufficient capital to absorb losses in the event of a hypothetical pronounced downturn in the Norwegian economy (See Section 3 Stress test).

Chart 2.10 Norwegian banks' Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital ratios1 Share of risk-weighted assets and total assets. Percent. 1996–2018

1) Consolidated figures where available. Parent banks otherwise.

Source: Finanstilsynet (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway)

Chart 2.11 Largest Norwegian banking groups' Common Equity Tier 1 capital ratios, leverage ratios and long-term capital targets Percent. At 30 June 2019

Sources: Banks’ quarterly reports and Norges Bank

Norges Bank supports the Ministry of Finance’s proposed changes to capital requirements