Financial stability outlook

The financial system in Norway has performed well during the Covid-19 pandemic. Government support measures have dampened the economic impact. There is considerable uncertainty regarding the future path of the pandemic and the consequences for the economy and financial markets. The financial stability outlook has therefore weakened somewhat. High household debt and high property prices remain the key financial system vulnerabilities in Norway. Substantial improvements in banking and financial regulation since the financial crisis in 2008 have increased resilience. Banks are robust and well capitalised, despite increased losses.

Extensive government support measures contribute to financial stability

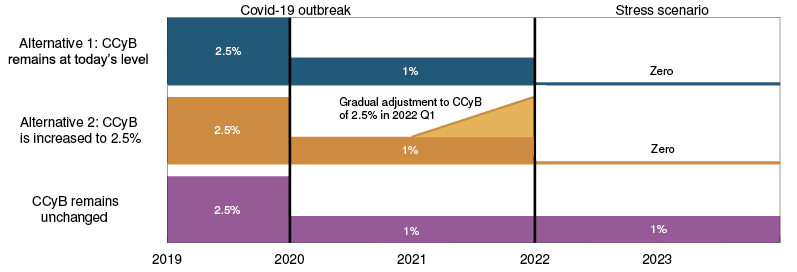

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to a deep downturn in the Norwegian economy. A partial lockdown of society and reduced domestic and foreign demand resulted in a significant fall in economic activity and high unemployment in spring 2020. The downturn was amplified by a fall in oil prices. Extensive government support measures have helped to dampen the impact of the pandemic on firms and households. Norges Bank reduced the policy rate to zero through spring, and the Ministry of Finance reduced the countercyclical capital buffer rate to 1% following advice from Norges Bank.

In addition to a sharp decline in the real economy, the Covid-19 outbreak led to considerable financial market turbulence, both globally and in Norway. Risk premiums on bank and corporate funding rose markedly, and the krone depreciated significantly. To support well-functioning markets, Norges Bank implemented extraordinary liquidity measures and intervened in the foreign exchange market. This contributed to dampening the turbulence in Norwegian financial markets. The financial infrastructure and payment system have functioned well, and their operations were stable during the crisis.

Uncertainty is high

Since May, there have been signs of improvement in the Norwegian economy. Activity has picked up, but the level is still lower than prior to the pandemic. Unemployment has declined, but it remains high. There is considerable uncertainty regarding both the near-term and long-term outlook. Infection rates have risen again, both abroad and in Norway, and more containment measures have been introduced. This will likely put a brake on the upswing in the coming period. It can take time before a vaccine becomes widely available, and new downturns are possible. Political processes globally may also result in shocks to the Norwegian economy. At the same time, fiscal and monetary policy space has become more limited in many countries. Meanwhile, owing to a resilient banking sector, the Norwegian financial system is well equipped to withstand shocks. On balance, the financial stability outlook has weakened somewhat.

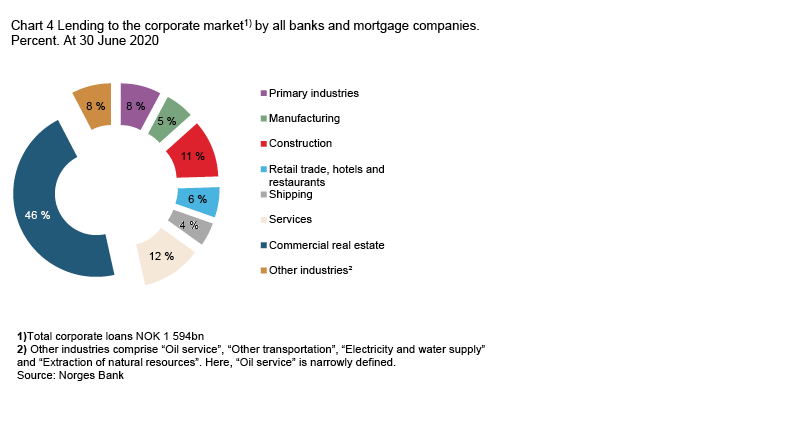

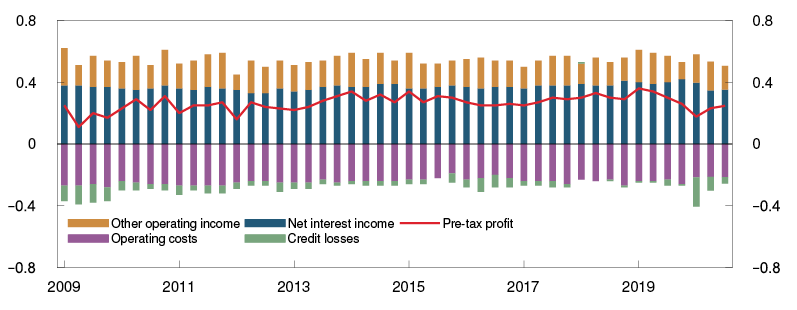

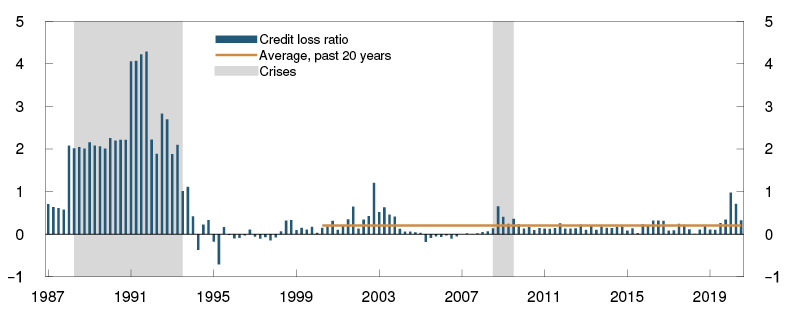

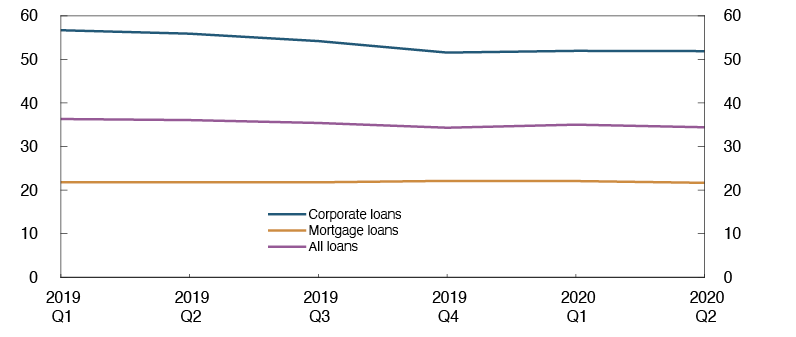

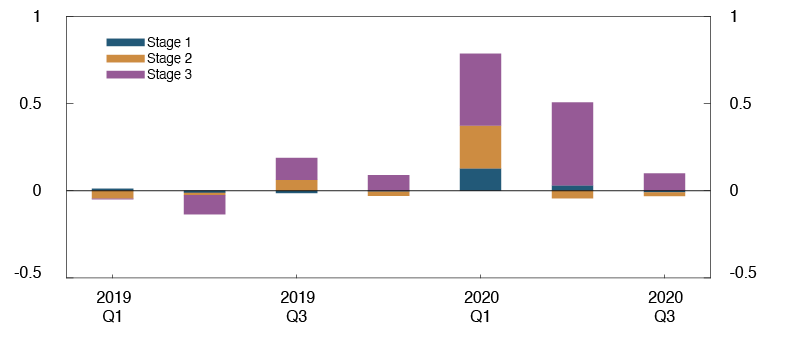

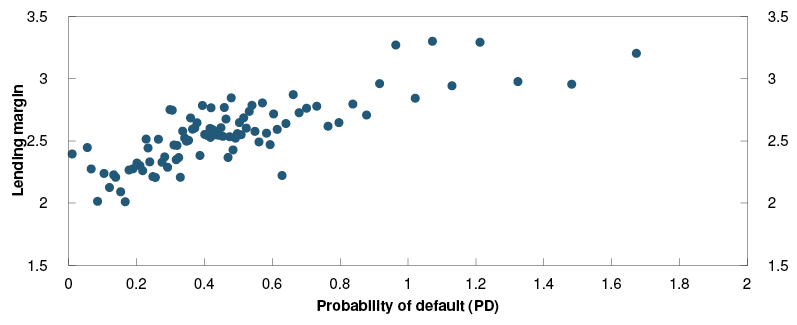

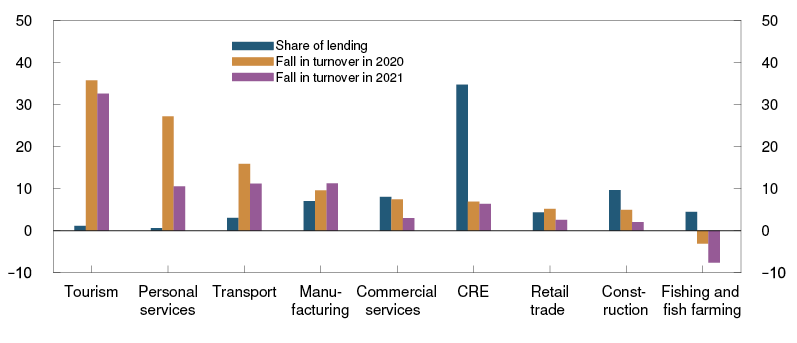

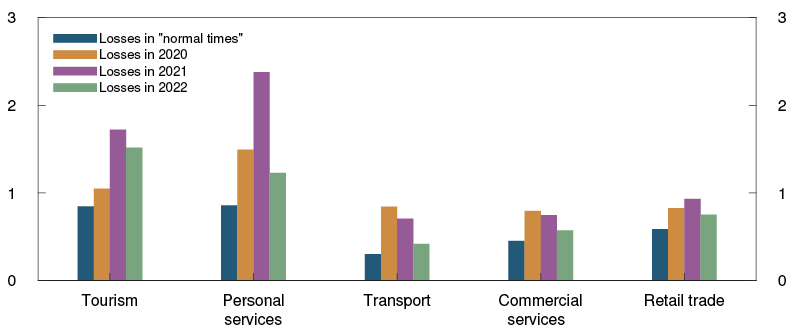

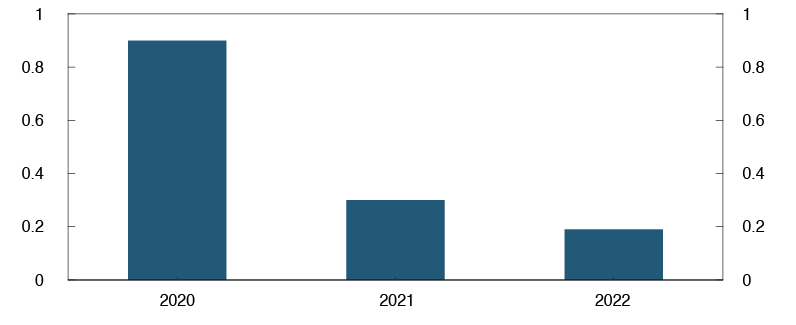

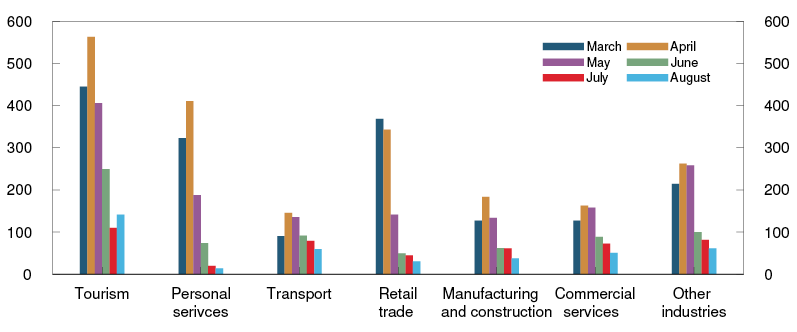

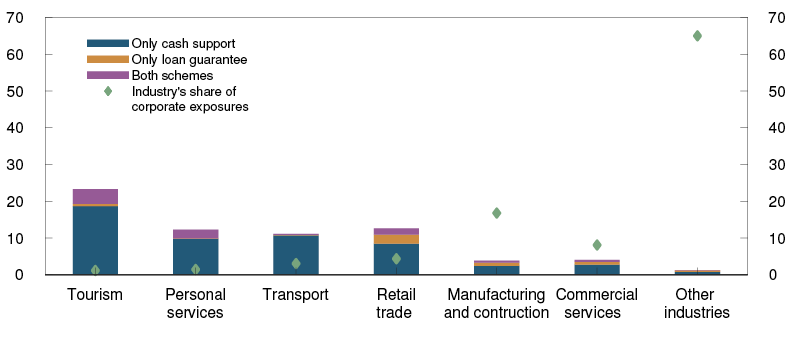

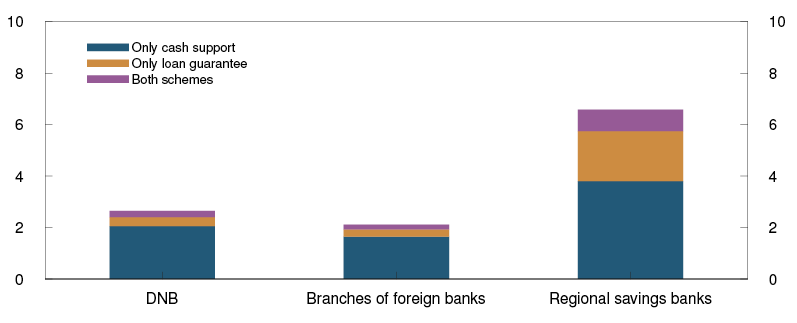

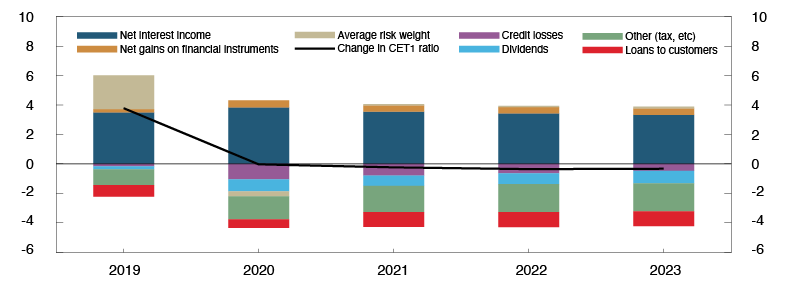

The Covid-19 pandemic and measures to contain it are weakening earnings for a number of Norwegian firms. The fall in oil prices led banks to recognise substantial impairment losses on oil-related exposures during the first half of 2020. Looking ahead, loss provisions may also increase in other industries. Analyses of Norwegian firms show that the industries hardest hit so far by the Covid-19 pandemic are not the ones with the most bank loans.

High household debt and high property prices are a source of financial system vulnerabilities

The key financial system vulnerabilities in Norway have long been high household debt, high house prices and high commercial property prices. These vulnerabilities are assessed as not substantially changed since Financial Stability Report 2019.

High debt increases household vulnerability to loss of income, higher lending rates and a fall in house prices. The risk that many households will tighten consumption at the same time represents a financial stability risk. Household leverage is at a high level. Debt growth has fallen somewhat since 2017, but has recently levelled off.

House prices are at a high level after having risen faster than household income over a long period. Since 2017, the rise in prices has been more moderate and lower than income growth. House prices fell in March and April in connection with the Covid-19 outbreak, but have risen markedly thereafter. If house prices continue to rise rapidly, vulnerabilities may increase.

Historically, selling prices for commercial real estate have risen substantially in advance of financial crises. Commercial property prices have risen for a long time and are at high levels. Selling prices for office space in Oslo fell in the first half of 2020, primarily owing to lower rents. Recently, however, the fall in selling prices has reversed, primarily driven by lower yields. Structural changes, such as increased use of remote working and online shopping, may affect developments in commercial property prices in the longer term. The Covid-19 pandemic may reinforce this trend. A substantial price fall may inflict large losses on banks. In recent years, banks have tightened lending conditions for commercial real estate, which limits the risk of losses.

Interest rate cuts make it easier for both households and firms to service debt. This reduces the risk of substantial tightening of consumption and may have a positive effect on firms’ earnings, which dampens banks’ risk of losses. At the same time, low interest rates over a longer period may fuel increased debt accumulation and a sharp rise in prices for both real estate and securities. This may amplify vulnerabilities and weaken the financial stability outlook.

Improved regulation since the last crisis has increased financial system resilience

Financial stability implies that banks and the rest of the financial system are able to perform their tasks adequately, even in the event of serious downturns and economic crises. Since the financial crisis in 2008, the Norwegian authorities have introduced a number of regulations to mitigate vulnerabilities in, and increase the resilience of, the financial system, in line with developments in international regulations. Stricter liquidity and capital requirements for banks have particularly helped to make banks more resilient to negative shocks. The authorities have introduced regulations covering residential mortgages, consumer credit and credit registers. This has contributed to limit lending to vulnerable households and the build-up of household sector vulnerabilities. In the opinion of Norges Bank, the requirements for prudent lending standards should be continued. In addition, the established credit registers should also contain information on collateralised loans to enable lenders and loan applicants to obtain the full picture of a loan applicant’s debt situation.

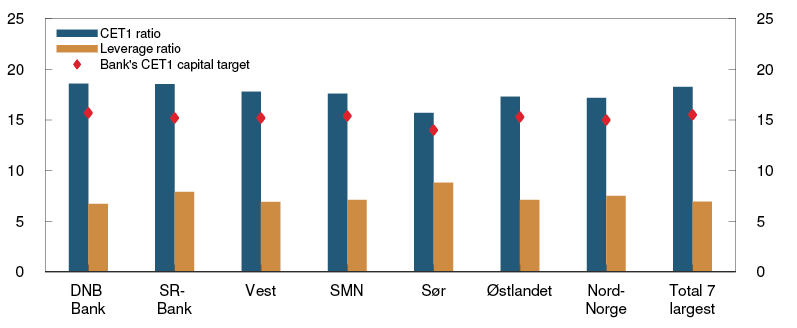

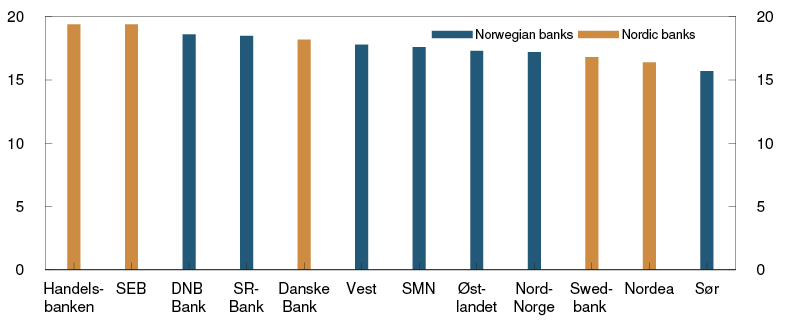

The resilience of the Norwegian financial system remains strong. Norwegian banks are profitable and well capitalised. They satisfy the capital requirements by an ample margin and have been capable of lending to households and businesses during the Covid-19 pandemic. Customers have also been given principal payment deferrals and short-term liquidity loans, which has supported economic activity. Analyses show that Norwegian banks are resilient and are able to absorb losses that are likely to materialise. At the same time, the outlook for losses is highly uncertain. The Ministry of Finance has urged Norwegian banks to wait before distributing a dividend or buying back shares until the uncertainty has abated further. A reduction in dividend payouts helps to strengthen loss absorbency and lending capacity, and in the period ahead, banks should continue to take into account the extraordinary situation the country is now facing.

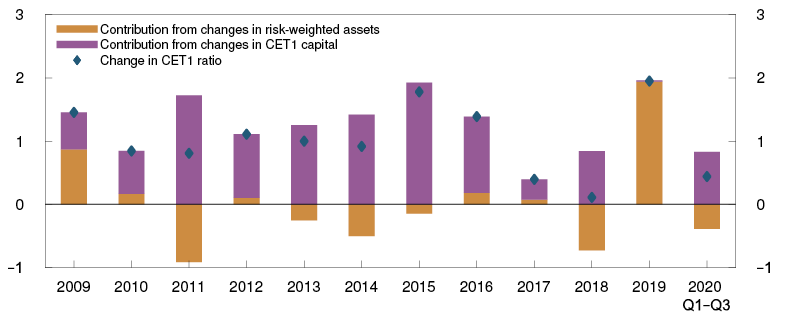

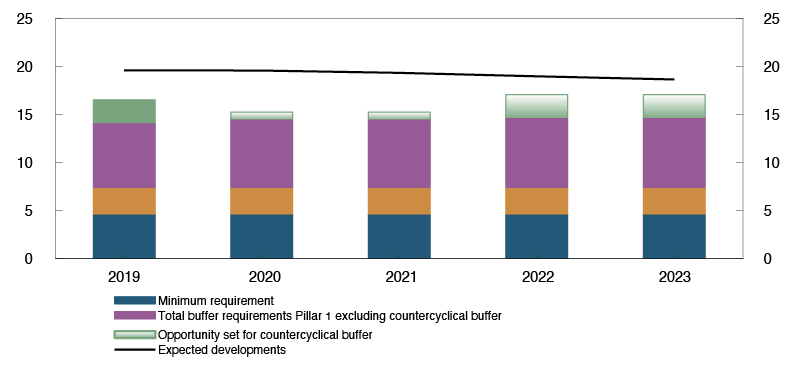

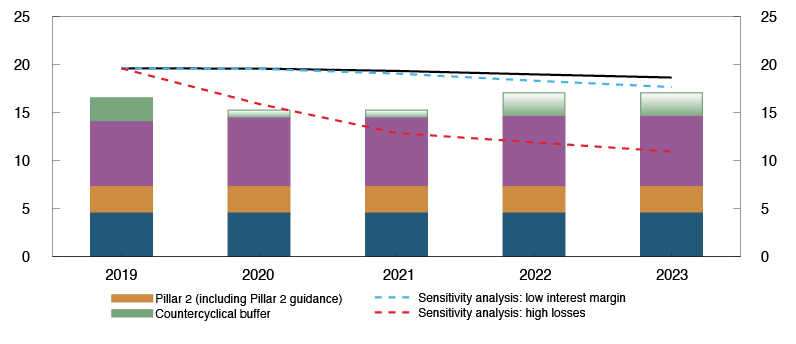

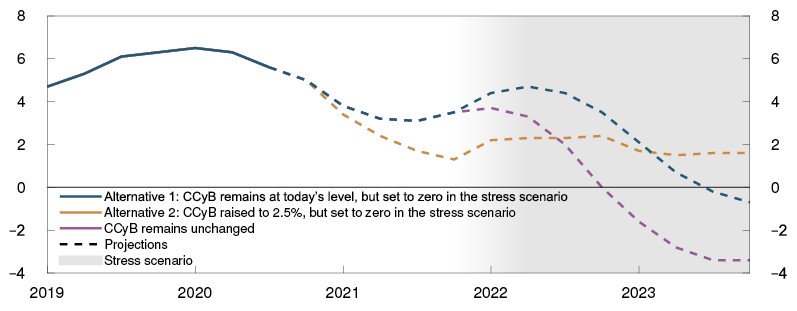

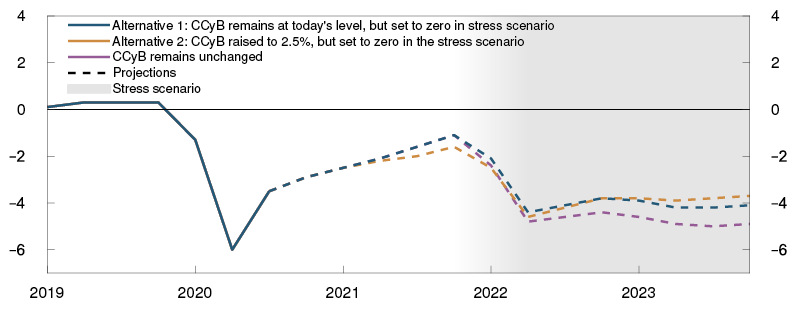

The stress test in this Report shows that banks can absorb higher losses. If economic developments prove weaker and losses prove higher than expected ahead, banks will be able to draw on buffer capital to avoid tightening lending. In such a situation, the authorities can reduce the countercyclical capital buffer to enable banks to maintain credit supply.

The countercyclical capital buffer shall normally be between 0% and 2.5%. A high countercyclical capital buffer rate helps ensure that the Norwegian banking sector is well equipped for future shocks. In setting the countercyclical capital buffer rate, improved loss absorbency capacity must be weighed against the consequences of possible credit tightening by banks to satisfy higher capital requirements. An illustrative exercise in this Report shows that the consequences of raising the buffer rate will depend on the situation in the economy and at banks. In a downturn, raising the buffer rate may delay a recovery. The tightening effect of a higher buffer rate may be less pronounced if, at the outset, banks satisfy the capital requirements by an ample margin or banks’ earnings are solid.

The regulatory changes following the financial crisis have strengthened the financial system, but the market turbulence in March uncovered some new challenges that the changes have led to. Margin requirements in derivatives trades have helped reduce the risk that insolvency will spread through the network of derivatives contracts. At the same time, requirements for daily margin payments to counterparties entail a liquidity risk, and it is important for parties to derivatives contracts to take account of this risk. The accelerating market turbulence in March resulted in substantial movements in financial markets that led to a high volume of margin calls, both in Norway and globally. In Norway, the sharp krone depreciation presented challenges to Norwegian asset managers. Liquidity challenges also affected other participants negatively, since they contributed to higher risk premiums in the bond market. Norges Bank will continue to assess the systemic risk associated with derivatives and, if necessary, propose changes to the rules for asset managers’ risk management.

The work on alternative reference rates will be important ahead

Reference rates play a key role in the financial system. In recent years, regulators in the UK and the US have worked to phase out Libor, the most important global reference rate. The transition from Libor to new reference rates globally may have consequences for Nibor, the most important reference rate in the Norwegian market. The increasing use by other countries of new risk-free overnight interest rates as a benchmark may lead to a need to phase out Nibor in the future as well. If users are not sufficiently prepared, this may constitute a risk to both individual institutions and to financial stability. The work to facilitate use of the alternative reference rate Nowa is well under way. Norges Bank urges Nibor users to make the necessary preparations to be able to adopt Nowa.

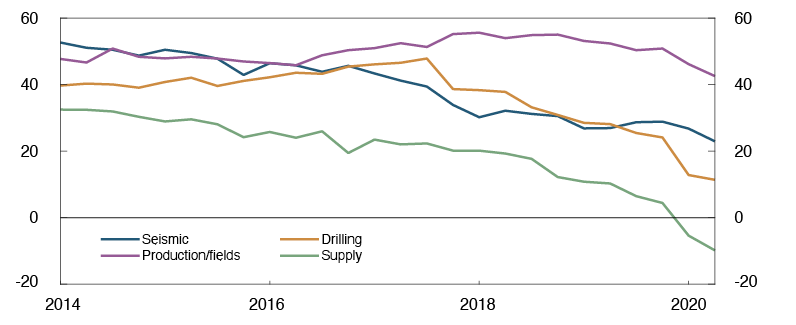

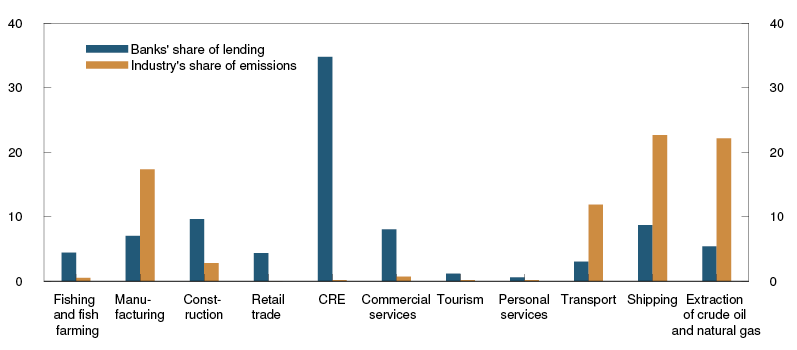

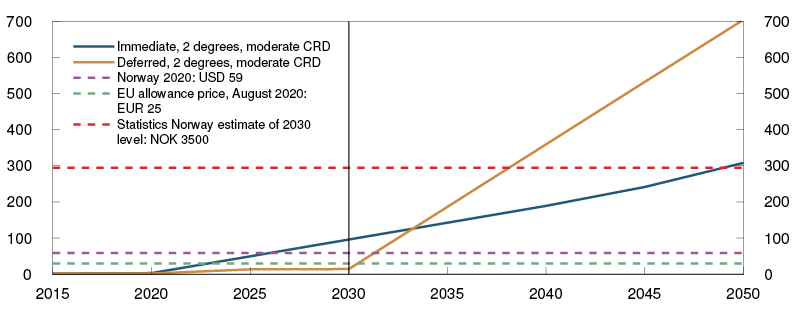

Important societal trends are important for financial stability

Climate change and the transition to a low-carbon economy will likely affect many firms in the years ahead. The Climate Change Act obliges Norway to substantial emission cuts in the coming years, and investors worldwide attach more weight to sustainable development than before. The biggest risk facing Norway is associated with developments in the value of the oil and gas industry. Norwegian banks also hold loans to international shipping, which may face stricter climate regulations in the coming years. It is important for banks to take climate risks into account in their risk assessments of both new and existing loans. The authorities can contribute to greater transparency regarding financial institutions’ climate risks through guidance, supervision and regulation. Through the EEA, Norway participates in the work to ensure better information about businesses’ climate footprint.

Cyber attacks are becoming increasingly widespread and sophisticated. Attacks have picked up during the Covid-19 pandemic, at the same time as all activity has become more dependent on digital solutions. The vulnerability of the financial system to cyber attacks has thereby increased. Financial Infrastructure Report 2020 points out that the Norwegian financial system is dependent on a few key ICT service providers. This in turn increases the risk that a cyber attack can represent a threat to financial stability. Norges Bank and Finanstilsynet (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway) have decided to establish a national framework (TIBER-NO) for testing cybersecurity in the banking and payment system in Norway.

Øystein Olsen Ida Wolden Bache Jon Nicolaisen Ingvild Almås Jeanette Fjære-Lindkjenn

27 October 2020

1 Balance of risks

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to a sharp downturn in both the Norwegian and global economy and severe stress in global financial markets. Actions taken by the authorities have dampened the downturn and market stress. There is considerable uncertainty surrounding developments ahead. Improvements in banking and financial regulation since the financial crisis in 2008 have strengthened the resilience of the financial system. The key financial system vulnerabilities in Norway are still high household debt and high property prices. Banks’ credit losses have increased, but banks are well capitalised.

Activity in the Norwegian economy has fallen abruptly as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, and the economy is now in the midst of a deep downturn. From 12 March, far-reaching measures were introduced to contain the spread of the virus. The containment measures have led to production halts and reduced activity across a range of businesses. The measures limited household demand. Many employees were furloughed or made redundant. Since then, activity in the Norwegian economy has picked up, and unemployment has fallen. At the end of August, the activity level in the mainland economy was still close to 4% lower than before the pandemic broke out in March. A significant increase in infection rates through autumn and stricter containment measures will likely put a break on the upswing in the coming period.

1.1 Risk of shocks

The Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in heightened global uncertainty

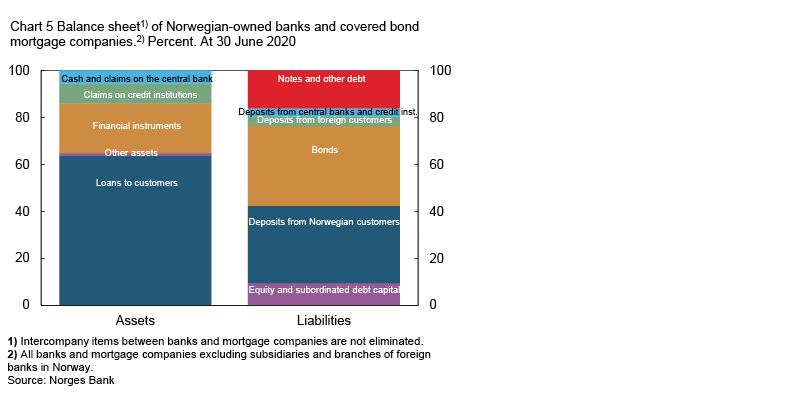

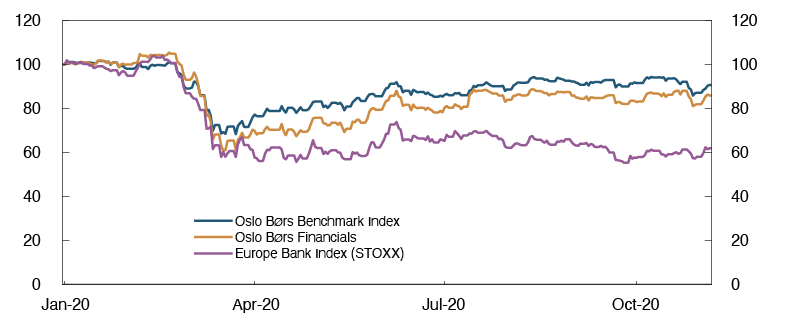

Uncertainty surrounding the economic consequences of the Covid-19 outbreak prompted a flight to presumed safety among investors, who sold off their higher-risk assets. Equity indexes fell sharply (Chart 1.1), risk premiums on debt instruments rose, and capital flowed out of emerging economies. Large withdrawals from securities and investment funds forced them to sell assets, which amplified the turmoil in financial markets.

Chart 1.1 Equity indexes fell sharply in March, but have recovered1 Index. 1 January 2008 = 100

Source: Bloomberg

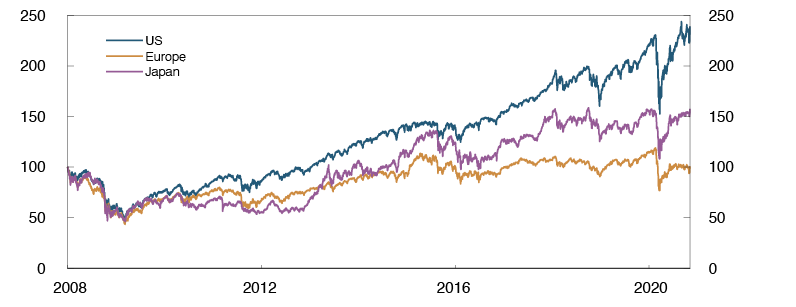

Extensive containment measures led to an abrupt fall in economic activity and a spike in market volatility. At the same time, the authorities in many countries implemented a number of measures to stabilise financial markets. Substantial provision of central bank liquidity via banking systems and central bank asset purchases were undertaken to deal with liquidity shortages. Central bank balance sheets grew (Chart 1.2). Many central banks cut policy rates to ease households’ and firms’ debt service burdens and stimulate the real economy. In many countries, extensive fiscal policy measures were swiftly implemented to dampen the downturn.

Chart 1.2 Central banks’ balance sheets grew2 In trillions of USD

Sources: Bank of Japan and IMF

The authorities in many countries also used macroprudential measures aimed at banks’ credit standards to mitigate the crisis. The purpose was to prevent the economic downturn from being amplified by reduced access to credit by residential mortgage and corporate customers. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) quickly extended new loans to emerging economies. The Paris Club3 agreed to grant suspensions of debt service payments on emerging economies’ loans. These measures contributed to maintaining financial stability.

Financial markets recovered quickly, and demand for higher-risk assets has increased. According to the IMF, the spread between market prices of equities and their value based on fundamentals is at very high levels in a number of advanced economies.4 IMF calculations also show that credit risk premiums in the bond market are lower than implied by fundamentals. Reduced risk-taking, higher inflation or other unanticipated events may result in substantial corrections in asset prices, with a corresponding fall in household and corporate financial wealth. This may have serious consequences for the rest of the economy. Recently, there has been renewed turbulence in global financial markets at the same time as a significant increase in infection rates and new containment measures.

Increasing global indebtedness

Globally, banks’ credit losses have risen, despite lower interest rates and other measures to support households’ and firms’ debt servicing capacity. Losses are expected to increase further when the measures are scaled back, especially in sectors directly affected by containment measures. The recent increase in Covid-19 infection rates and additional containment measures will likely put a brake on the upswing.

In several countries, the corporate sector was already highly indebted prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. New borrowing to address liquidity challenges have amplified these vulnerabilities. This debt will be more vulnerable if lower growth prospects weaken or government support measures are scaled back prematurely. Uncertainty regarding the pandemic ahead amplifies the global uncertainty concerning economic developments and financial conditions, and policy rates may remain low ahead. Low interest rates make it easier to service debt in difficult periods but may fuel debt growth and increase private sector vulnerabilities further out.

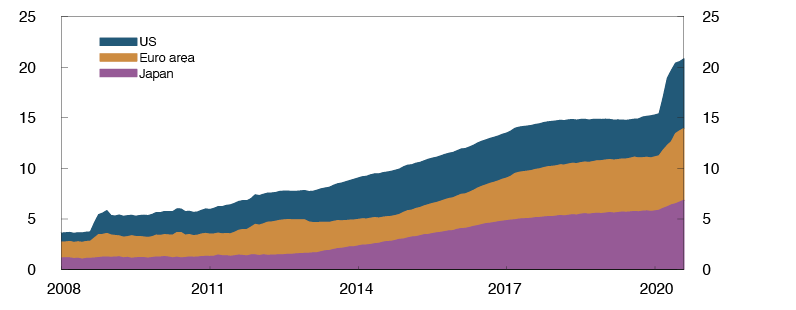

Among advanced economies, the real economy has recovered rapidly after the lockdowns in the first half of 2020, but the IMF expects that advanced economy GDP will not pass pre-pandemic levels until 2022 at the earliest. Against the background of very expansionary fiscal policies, public debt-to-GDP ratios are rising sharply across countries (Chart 1.3). Higher public debt can reduce fiscal space in a number of countries, narrowing the scope for action if new shocks materialise.

Chart 1.3 Fiscal policy measures are increasing public debt5 Public debt as a share of GDP. Percent

Source: IMF

The UK left the EU on 31 January 2020. A transitional agreement that primarily extends the terms of membership expires at the end of this year. For the time being, no Brexit deal is in place. The financial industry and the authorities have concluded extension agreements in some essential areas. The risk of financial market turbulence if no deal is reached is now lower than in 2019. Generally, renewed turbulence internationally may result in new shocks to the Norwegian economy.

Considerable stress in Norwegian financial markets

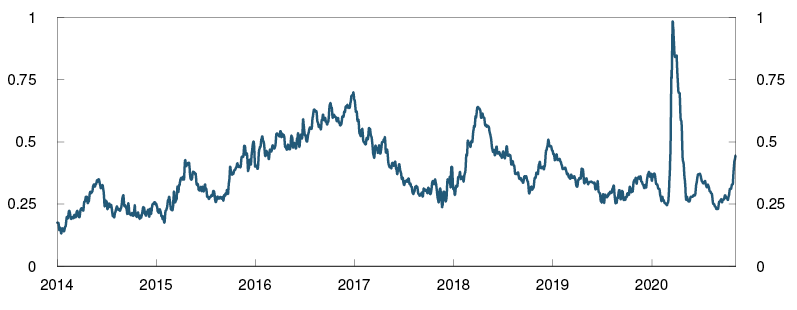

In the wake of the Covid-19 outbreak and oil price fall, there was also considerable stress in Norwegian financial markets in March. Equity indexes fell, and bond and money market risk premiums rose (Chart 1.4).

Chart 1.4 Norwegian money market premiums rose sharply in March6 Difference between the three-month money market rate and expected policy rate. Percentage points

Sources: Refinitiv Datastream and Norges Bank

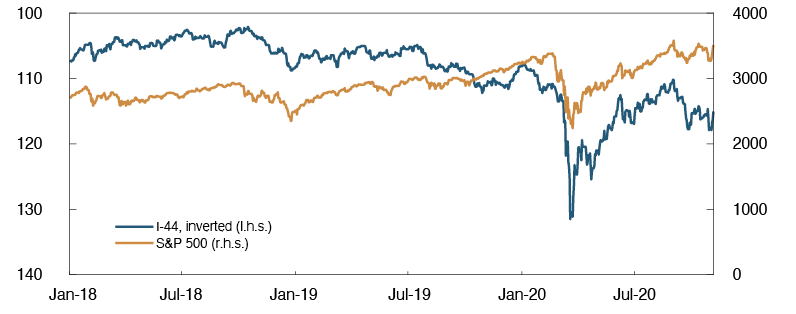

The financial market turmoil affected both banks and other market participants. Risk premiums on banks’ wholesale funding rose markedly and access to funding was reduced. Large corporates that obtain financing directly in the bond market were also affected. The krone exchange rate, measured by the import-weighted exchange rate index I-44, reached record weak levels in March. Substantial volatility in market prices led to increased margin calls on derivatives contracts in a number of countries. The sharp krone depreciation magnified the impact on Norway, and a number of market participants experienced problems obtaining liquidity. For that reason, many had to sell securities (see "Asset managers faced liquidity stress during the foreign exchange market turbulence in March").

Like other central banks, Norges Bank implemented a number of measures to improve market liquidity and ensure pass-through of the policy rate (see "Annex"). Banks were offered extraordinary loans, and to promote a well-functioning market for NOK, Norges Bank undertook extraordinary NOK purchases in the foreign exchange market. In the IMF’s assessment, the Norwegian liquidity management system functions well both in normal times and in crises (see "IMF: The Norwegian authorities have taken welcome steps to strengthen the financial system" and "Who may hold an account with Norges Bank?").

In summer and early autumn, the uncertainty in global financial markets abated and oil prices rose. At the same time, the krone appreciated, equity indexes advanced and money and bond market premiums fell. Recently, there has been renewed turbulence in global and domestic financial markets at the same time as a significant increase in infection rates and new containment measures, which impede economic activity.

1 Period: 1 January 2008 – 5 November 2020.

2 Period: January 2008 – August 2020.

3 An informal group of official creditors, with the permanent participation of 22 countries with large exposure to other sovereigns worldwide.

4 See International Monetary Fund (2020) “Bridge to Recovery”. Global Financial Stability Report. IMF, October 2020.

5 Period: 2012–2020. Projections for 2020. Gross debt.

6 Period: 1 January 2014 – 5 November 2020. Five-day moving average.

1.2 Developments in financial system vulnerabilities in Norway

Financial system vulnerabilities are important in the event of negative shocks. The key financial system vulnerabilities in Norway are high household debt and high property prices (see box on this page).

Key financial system vulnerabilities in Norway

The arrows indicate whether vulnerabilities have increased, decreased or remained unchanged since the 2019 Report.

The table above shows Norges Bank’s assessment of the key vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system. Vulnerabilities can be time-varying or the result of permanent structural conditions in the financial system. Vulnerabilities can cause or amplify financial turbulence and an economic downturn when the economy is exposed to large shocks. The interaction between shocks and vulnerabilities can result in financial crises that restrain economic growth. Shocks that trigger financial crises can be difficult for the authorities to predict and influence. A small open economy like Norway is at risk from external shocks.

The vulnerability assessment is based on historical experience of what causes downturns and financial turbulence and assessments of new features of the financial system. The vulnerabilities identified as key vulnerabilities may change over time.

Norges Bank will, as needed, issue advice on measures to address vulnerabilities. These may be measures aimed at reducing the vulnerabilities directly or increasing financial system resilience. The authorities have already implemented a number of measures (Table 1 in "Annex".

The Covid-19 pandemic and the introduction of measures to contain it led immediately to lower turnover for many businesses, a substantial rise in unemployed and a fall in property prices. The consequence is reduced incomes, which weaken borrowers’ debt servicing capacity. Lower property prices reduce the value of banks’ collateral. Subsequently, activity in the Norwegian economy has picked up. House prices have also risen markedly through summer and autumn and are higher than prior to the pandemic. Recently, commercial property prices have risen as well.

Banks’ credit losses have risen during the Covid-19 pandemic, but lower operating expenses and retained earnings have contributed to solid solvency levels. Norwegian banks have maintained the supply of credit to firms and households. The stress test in this Report indicates that Norwegian banks are solvent and will weather increased credit losses in the event of a new downturn in the Norwegian and global economy. (See further discussion of banks in Section 3 and the stress tests in Section 5.)

Borrowers who are unable to cope with climate change and the transition to a low-emission society constitute a risk for banks (see Section 4). Norwegian banks must be prepared for the possibility that their exposures will be affected by climate change and measures to address it.

Digitalisation is helping to make Norwegian banks cost-efficient. At the same time, the financial system is vulnerable to both unintended operational incidents and cyber attacks. Attacks on financial institutions have increased substantially in 2020. Malicious attacks or operational incidents have so far not resulted in extensive disruptions in the Norwegian financial system.

IMF has recently assessed the financial system in Norway. Their conclusion is that measures implemented in recent years have strengthened the resilience of the system, but at the same time, they point out further areas for improvement (see "IMF: The Norwegian authorities have taken welcome steps to strengthen the financial system").

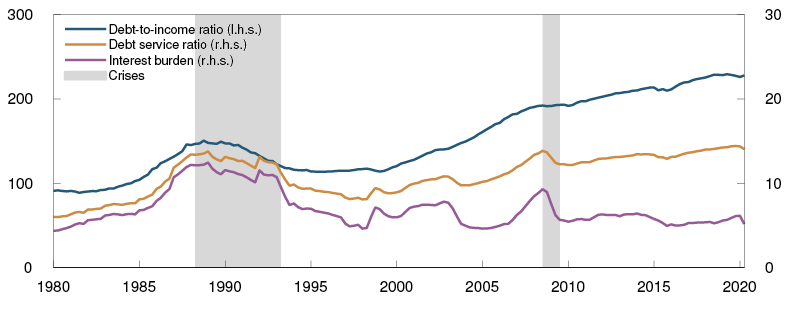

Measures have limited the increase in vulnerabilities associated with high indebtedness

After a long period when household debt grew faster than household income, debt growth has slowed in recent years and has been more in line with income growth. Reduced debt growth reflects the interest rate increases in 2018 and 2019 and measures by the authorities to limit borrowing (see"Regulation of financial institutions’ credit standards"). After the Covid-19 outbreak, household debt growth has continued to be moderate. Household leverage (debt-to income ratios) remains high, both historically and compared with other countries, but is at about the same level as in 2019 (Chart 1.5). Household leverage will continue to increase somewhat ahead as low interest rates stimulate borrowing, while the Covid-19 pandemic contributes to weaker income growth.

Chart 1.5 Debt-to-income ratios are high but have shown little change in recent years7 Debt-to-income ratio, debt service ratio and interest burden. Households. Percent

Sources: Statistics Norway and Norges Bank

The Covid-19 pandemic and containment measures led to a sharp increase in the number of unemployed. At the same time, lower borrowing rates helped to bolster the finances of indebted households, and many obtained deferred principal repayments of their bank loans. Subsequently, the number of unemployed has declined. Despite a fall in household income in 2020 Q1 and Q2, the saving ratio increased. Households have so far not increased credit card use to get through the crisis. According to debt data from Gjeldsregisteret, both interest-bearing and non-interest-bearing credit card debt has fallen since the Covid-19 outbreak.

Owing to low interest rates, households’ interest burdens, ie the share of income going to interest payments on loans, are low from a historical perspective, despite high household leverage. Even though low interest rates make it easier to service debt, high household leverage means that changes in interest rates have a greater impact on interest burdens than before. Overall debt service ratios, which include both interest and principal, are relatively high and signal high risk in the heatmap (see "Developments in the heatmap").

High debt levels make households vulnerable to loss of income, an increase in lending rates or a fall in house prices. At the same time, the risk that many households will tighten consumption also constitutes a financial stability risk. Such a tightening may contribute to amplifying a downturn in the Norwegian economy. This may reduce firms’ earnings and debt servicing capacity and then result in higher losses on banks’ corporate exposures.

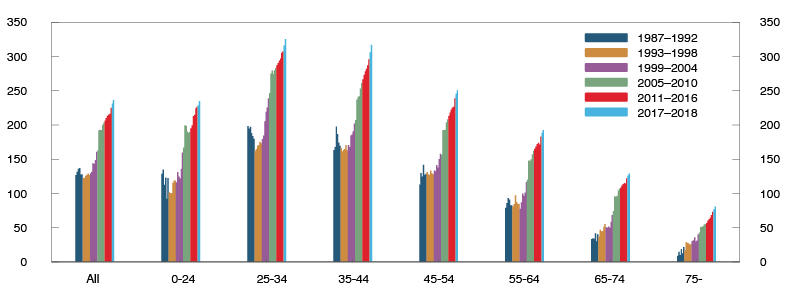

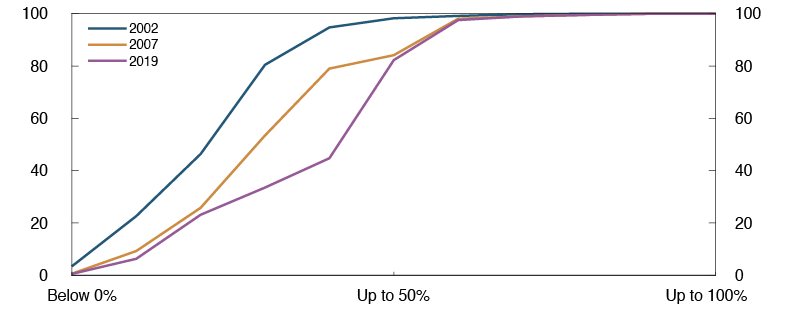

Tax return data from 2018 show that average household debt continued to rise in all age groups, but growth was restrained somewhat compared with the previous year. There was still a rise in leverage (Chart 1.6). Preliminary tax return data for 2019 indicate a more moderate rise in leverage in most age groups and a weak decline among younger age groups.8

Chart 1.6 Debt as a share of after-tax income has risen in all age groups9 Percent

Sources: Statistics Norway and Norges Bank

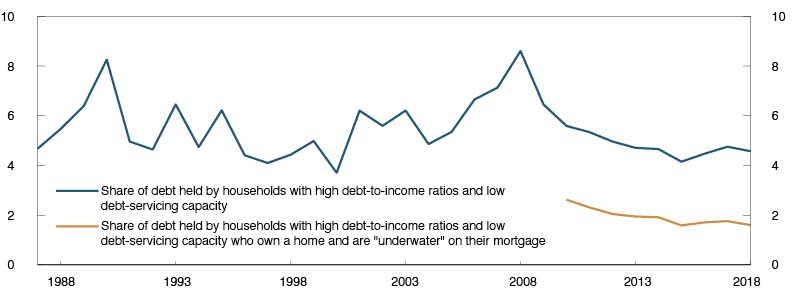

Tax return data show that the share of highly leveraged houseolds (debt over five times gross income) and households with low debt servicing capacity (annual margin below one month’s income) has stabilised in recent years. The share of households “underwater” (net bank debt higher than their dwelling’s market value) is also stable. Households with both high debt and low debt servicing capacity that at the same time are also underwater (if they are homeowners) have less flexibility in the event of negative shocks. The debt held by these households is assumed to be particularly vulnerable. This debt represents a small share of household debt. This share fell back somewhat in 2018 after rising the two previous years (Chart 1.7). The residential mortgage regulation has contributed to limiting new lending to vulnerable households,10 thereby reducing the build-up of housing sector vulnerabilities.

Chart 1.7 Vulnerable households hold a small share of debt11 Share of total household debt. Percent

Sources: SIFO, Statistics Norway and Norges Bank

Consumer credit, which is unsecured debt, grew sharply over several years. However, such debt accounts for a limited share, around 3%, of household debt. After the introduction of the consumer credit regulation in 2019 and the establishment of credit registers, the volume of consumer credit fell. However, defaults have risen12, and there are still many households with consumer debt that can be difficult to manage. Owing to high interest rates, interest burdens are high for those with substantial consumer debt. Even though persons with total consumer debt of over NOK 1m or more or with more than 10 consumer loans only account for 2.5% of all persons with consumer debt, they hold all of 26% of such debt. The regulation of credit standards and the transparency provided by credit registers are intended to ensure that the maximum debt-to-income and debt servicing capacity requirements are followed when borrowers take on new consumer debt.

Overall, the vulnerabilities associated with household debt are assessed as broadly unchanged since 2019.

Regulation of financial institutions’ credit standards

To mitigate the build-up of high debt levels among vulnerable households, the Norwegian authorities have set requirements for banks’ and other financial institutions’ credit standards. Residential mortgage loans have been subject to a regulation since 2015, and a consumer credit regulation was issued in 2019. Both regulations expire on 31 December 2020. A proposal for the regulations to remain in force has been circulated for public comment.

In Norges Bank’s assessment, the regulation credit standards have worked well.1 The requirements provide a clear limit for prudent credit standards and have contributed to restricting lending to vulnerable households.2 The quotas enable banks to grant loans in breach of the requirements based on a customer-specific assessment. The flexibility quotas underpin financial institutions’ own responsibility for prudent credit standards. Credit regulation entails a trade-off between ensuring efficient credit markets and limiting the build-up of risk in the financial system.

Norges Bank is of the opinion that regulation of lending should continue. To increase regulation transparency, and to emphasise that it is total household debt that is important for vulnerability, it is appropriate to consolidate lending regulations in one regulation. Including other types of loans in the regulation and the credit registers will also help to prevent borrowers from circumventing the rules. Credit registers provide an overview of individual borrowers’ unsecured debt. The credit registers should be expanded to include residential mortgage loans. Other types of loans that will be covered by the lending regulation should also be included in the credit registers following an assessment of the scope of lending and the costs associated with such reporting. This expansion will give individuals a clearer overview of their debt situation and strengthen the basis for banks’ and other financial institutions’ credit assessments of individual borrowers. The interest of consumer protection suggests that the flexibility quota associated with consumer credit should be low or zero.

The requirements in the lending regulation should be assessed at regular, but not frequent, intervals. In special cases, the flexibility quotas can be adjusted outside of the fixed dates for assessing the requirements in the regulation. During the sharp downturn in the Norwegian economy in spring, the flexibility quotas were temporarily expanded to 20% in 2020 Q2 and Q3. In the event of a marked increase in household sector vulnerabilities resulting from rapidly rising debt and house prices, it should be possible to tighten the flexibility quotas.

Table 1.A Requirements in the current residential mortgage loan regulation and consumer credit regulation

|

Requirement |

Residential mortgage loan regulation |

Consumer credit regulation |

|

Maximum loan-to-value (LTV) ratio1 |

||

|

Debt-servicing capacity |

||

|

– Tolerate interest rate increase |

5 percentage points |

5 percentage points |

|

– Maximum total debt (debt-to-income ratio) |

5 times gross income |

5 times gross income |

|

– Required principal payments |

2.5% annually with LTV > 60% |

Monthly principal repayments over 5 years |

|

Regional requirements |

Maximum LTV 60% for secondary home purchases in Oslo |

|

|

Flexibility quota2 |

10% excluding Oslo 8% in Oslo |

5% |

1 Residential mortgage debt/house value incl. additional collateral.

2 Share of new residential mortgage loans per quarter for which banks may deviate from the requirements.

1 See Norges Bank’s consultation response in a letter to the Ministry of Finance of 10 November 2020.

2 See box “The regulation on residential mortgage loans has limited loans to vulnerable households” in Monetary Policy Report 3/20, Norges Bank.

House price inflation has increased again

High house prices represent an important financial system vulnerability in Norway. Household debt is dominated by residential mortgage loans, and debt developments are closely associated with house price developments. At the same time, housing wealth accounts for a substantial share of household wealth. Sharp and sudden falls in house prices may trigger tightening of household consumption and result in increased losses on banks’ loan portfolios.

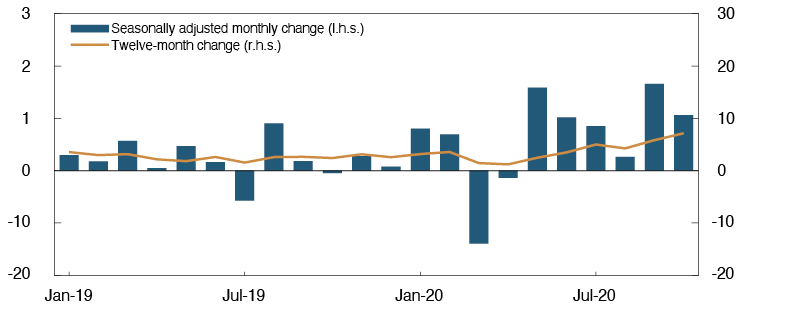

The Covid-19 pandemic and containment measures led to a substantial decline in housing market activity, and house prices fell (Chart 1.8). Through summer, turnover picked up to a historically high level and has largely remained elevated through autumn. House price inflation moved up quickly and has been high through summer and autumn. The 12-month rise has increased from 1% in April to 7% in October, well above the average for the past 10 years. Both very low residential mortgage rates and probably also the temporary relaxation of the residential mortgage regulation13 have contributed to developments. At the same time, higher unemployment has largely affected low-income occupations, who are less likely to purchase a home.

Chart 1.8 Marked increase in house price inflation14 Percent

Sources: Eiendomsverdi, Finn.no and Real Estate Norway

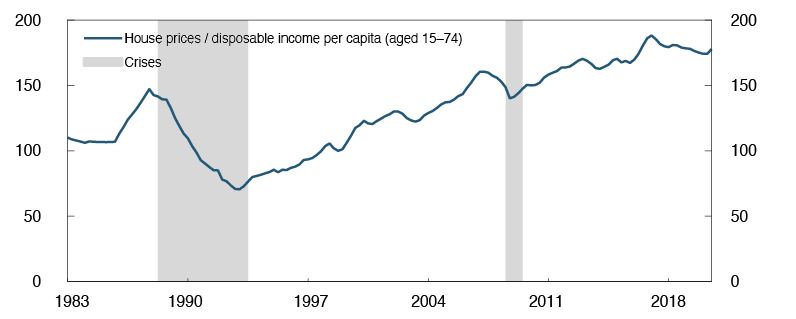

Developments in house prices relative to household income are important for assessing vulnerabilities associated with house prices. For many years, house prices rose more than household income (Chart 1.9). After the residential mortgage regulation was tightened in 2017, the opposite was the case for a long time. Owing to a marked upswing in house price inflation after the decline in March and April, combined with moderate income growth, house price inflation exceeds income growth again (see Monetary Policy Report 3/20).

Chart 1.9 House prices have risen less than household income in recent years15 Index. 1998 Q4 = 100

Sources: Eiendomsverdi, Finn.no, Norwegian Association of Real Estate Agents (NEF), Real Estate Norway, Statistics Norway and Norges Bank

Overall, vulnerabilities associated with high house prices are assessed as broadly unchanged from 2019. There is considerable uncertainty regarding developments ahead, and if house prices continue to rise rapidly, vulnerabilities may increase.

Commercial property prices are back to pre-downturn levels

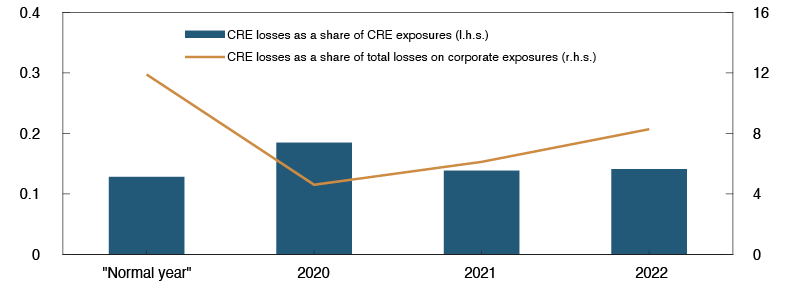

Commercial real estate (CRE) loans, which are mortgages secured on commercial property, account for around 40% of banks’ total corporate exposures. The CRE sector is distinguished by particularly high debt-to-turnover ratios, and experience shows that exposures to this sector can inflict heavy losses on banks in the event of pronounced downturns. This poses a risk to financial stability.

The economic downturn that Norway is in the midst of has reduced demand in the rental market. On the other hand, the stimulus packages have enabled more firms to maintain their leases, despite periods of low sales. Looking ahead, it is uncertain how experience from the crisis will affect demand in the rental market. If the pandemic leads to structural changes, eg increased use of remote working and video conferencing, this will reduce the need for office space and affect developments in rents. In the retail sector, the trend towards increased online shopping may have a negative impact. See Section 4 for a further discussion of the CRE sector.

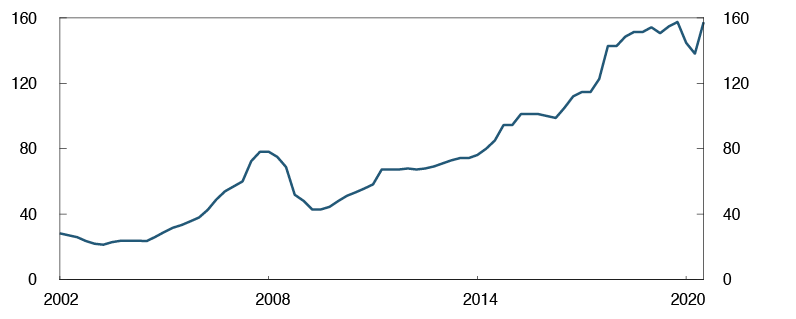

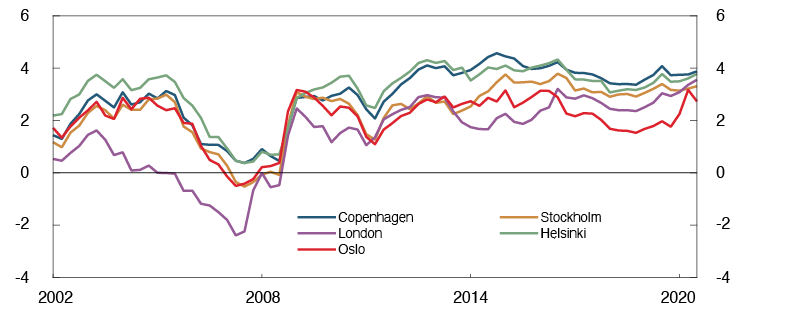

A relatively large share of the stock of office buildings is in Oslo, and selling prices for prime office space in Oslo are therefore an important indicator of CRE sector vulnerabilities. Selling prices are estimated as the ratio between rents and yield16. In the first half of 2020, selling prices fell, primarily owing to lower rents (Chart 1.10). In Q3, the yield fell substantially and contributed to a reversal of the decline in selling prices in the first half of 2020. The yield is now at a very low level. However, the yield has fallen less than interest rates since the turn of the year, which implies a higher risk premium and downward-adjusted expectations of a rise in rents (Chart 1.11). This indicates a somewhat lower risk of a more pronounced fall in selling prices ahead. At the same time, the gap between the yield in Oslo and long-term interest rates is still at a somewhat lower level than in many other European cities.

Chart 1.10 Commercial property prices back to pre-downturn levels17 Prime office space in Oslo. In thousands of NOK per square metre

Source: CBRE

Chart 1.11 Risk premium on CRE in Oslo somewhat lower than in other European cities18 Percentage points

Sources: CBRE and Datastream

Vulnerabilities associated with the CRE market are assessed as broadly unchanged since 2019.

IMF: The Norwegian authorities have taken welcome steps to strengthen the financial system

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has conducted a comprehensive assessment of the Norwegian financial system.1 The IMF assesses member countries under its Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP). The goal is to assess strengths and weaknesses, and to recommend measures to strengthen the resilience of the financial system at both a national and international level. IMF assessments are a part of the Norwegian authorities’ continuous efforts to strengthen the Norwegian financial system.

The IMF concludes that a number of measures taken by the Norwegian authorities have contributed to strengthening the Norwegian financial system since the previous assessment in 2015. The capital position of banks and insurance companies has been bolstered, the terms for mortgage loans have been tightened and new legislation on crisis resolution has been implemented. Nonetheless, vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system remain. The IMF identified the most prominent risk factors as being banks’ exposure to a residential real estate market marked by high prices and high household debt, and banks’ reliance on international wholesale funding markets. The IMF also assesses banks’ climate-related risk, and its findings suggest that sharp increases in carbon prices would have a significant, but manageable impact on banks’ loan losses.

The IMF’s key findings and recommendations

- The IMF’s recommendations do not imply any substantial change in the use of macroprudential tools. The IMF nevertheless recommends that the authorities should consider broadening the toolkit for addressing CRE risks, and that residential mortgage regulation should be a permanent feature of the macroprudential toolkit. The Norwegian authorities should also develop a macroprudential policy strategy.

- Norway’s institutional set up for macroprudential policy, where the Ministry of Finance is the macroprudential authority, is unusual, but has functioned. The IMF recommends that Norges Bank should be given recommendation powers over tools, such as the systemic risk buffer and the liquidity coverage ratio in significant currencies, that can be relaxed in a crisis situation. The IMF finds that Norges Bank has an effective system for managing liquidity in normal times and in times of crisis. Further analyses and monitoring of available collateral across Norges Bank’s counterparties would allow the Bank to better gauge the impact of changes in liquidity regulation.

- The IMF recommends that Finanstilsynet be given increased independence as the resolution authority and that involvement of the Ministry of Finance should be limited to resolutions that require public funds. Moreover, the Norwegian Banks’ Guarantee Fund should be further integrated into the authorities’ resolution framework. It would also be useful to establish a coordinating body for the authorities involved, with activities related to crisis prevention and management.

- For the first time, the work on cybersecurity risk was included in the FSAP. Norges Bank’s work in this area is characterised as advanced, and the IMF notes that the system for information sharing between the authorities is well established. Reporting of cybersecurity incidents should nevertheless be improved by establishing clearer thresholds for incident reporting and further defining what should be reported.

1 See International Monetary Fund (2020): “Norway: Financial Sector Assessment Program”. Country Report No. 2020/259. In addition to that main report, there are also more technical documents on: Financial Safety Nets, Systemic Liquidity, Systemic Risk Oversight and Macroprudential Policy Framework, Cybersecurity Risk Supervision and Oversight, Banking Regulation and Supervision and Insurance Sector Oversight.

7 Period: 1980 Q1 – 2020 Q2. Debt-to-income ratio is loan debt as a percentage of disposable income. Disposable income is income after taxes and interest payments. Debt service ratio is interest expenses and estimated principal payments as a percentage of after-tax income. Interest burden is interest expenses as a percentage of after-tax income.

8 See the analysis attachment to Norges Bank’s letter to Finanstilsynet of 16 September 2020 for a discussion of both household data and person-level data (Norwegian only).

9 Period: 1987–2018.

10 See Monetary Policy Report 3/20, page 54.

11 Period: 1987–2018. Vulnerable households are households in breach of critical values for debt-to-income ratio (debt over five times gross income) and debt-servicing capacity (annual income after tax, less interest and standard consumption expenditure of less than one month’s income) and from 2010 also critical value for debt-to-value (net debt higher than dwelling’s market value).

12 See Finanstilsynet (2020) Utviklingen i forbruksgjeld 2020 [Developments in consumer debt 2020] (Norwegian only).

13 The flexibility quotas, which allow banks to grant mortgages in breach of the requirements of the residential mortgage regulation, were enlarged in 2020 Q2 and Q3.

14 Period: January 2019 – October 2020.

15 Period: 1983 Q1 – 2020 Q3. Disposable income is income after taxes and interest payments. Adjusted for a break in the series. Data for 2020 Q3 contain projections for disposable income from Monetary Policy Report 3/20.

16 The yield depends on the risk-free interest rate, risk premium and the expected rise in rents.

17 Period: 2002 Q1 – 2020 Q3.

18 Period: 2002 Q1 – 2020 Q3. Yield prime office space less five-year swap rate.

Asset managers faced liquidity stress during the foreign exchange market turbulence in March

Norwegian asset managers experienced liquidity stress during the market turbulence in March, resulting in fire sales of securities. This led to a sharp rise in bond market risk premiums. One reason for asset managers’ liquidity needs was the sudden, sharp depreciation of the Norwegian krone. The krone depreciation resulted in increased margin calls on foreign exchange swaps. The event uncovered a vulnerability to large market movements associated with the use of derivatives contracts. Similar liquidity stress prompted by margin calls also arose in other countries.

Asset managers hedge their foreign currency positions using foreign exchange swaps

Asset managers – fund managers, life insurance companies and pension funds – play an important role in the financial system. They manage savings by offering investments in equities, bonds and real estate in Norway and globally. Their activities also help facilitate the equity and debt financing of Norwegian and foreign firms.

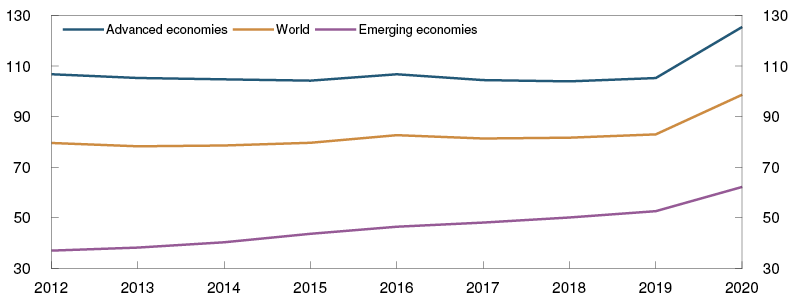

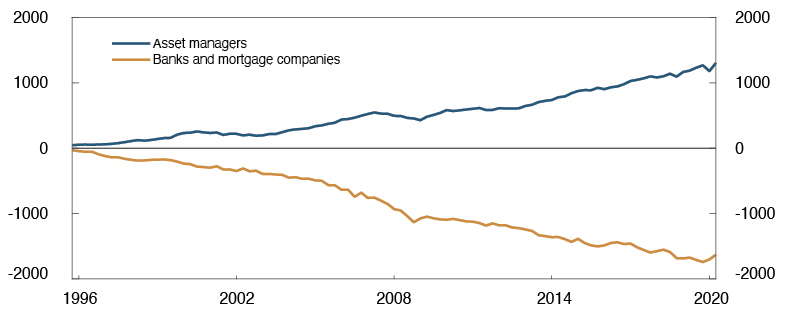

Whereas asset managers invest abroad, banks fund themselves abroad in part (Chart 1.A). While this makes sense in a small open economy, it also results in a need for banks to hedge their foreign currency borrowing against the risk of a krone depreciation. Similarly, asset managers may, on behalf of their investors (unit holders), prefer to neutralise all or part of the foreign exchange rate risk associated with investments in foreign assets. For investors, who care about returns in NOK, a krone appreciation is costly. A stronger krone results in a lower NOK return on foreign currency-denominated investments. How much foreign exchange rate risk asset managers choose to neutralise (“hedge”) depends on both the regulatory framework and investors’ risk appetite. Hedging is often accomplished using foreign exchange swaps.

Chart 1.A Asset managers invest abroad – banks borrow abroad1 Net financial claims on other countries. In billions of NOK

Sources: Statistics Norway and Norges Bank

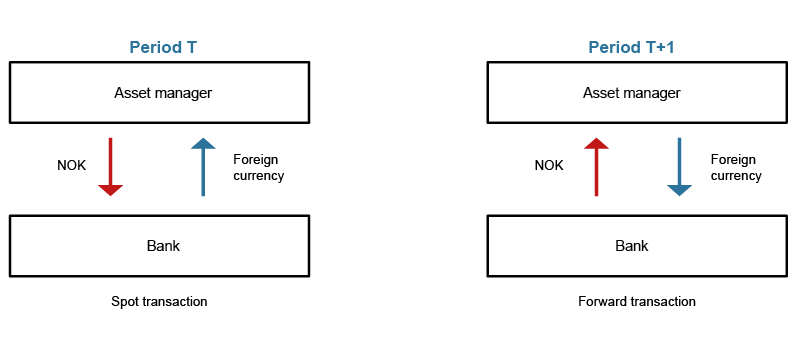

Foreign exchange swaps are derivatives that combine a spot and a forward transaction. As such, they enable asset managers to repatriate investments in NOK without foreign exchange rate risk. At the same time, for their part, banks enter into foreign exchange swaps to hedge their foreign currency borrowing: the bank can swap the foreign currency liabilities into NOK, which it can lend to customers. In addition, the bank receives foreign currency at a future date at a predetermined exchange rate. This enables the bank to repay its foreign currency loan without foreign exchange rate risk. Differing needs for foreign currency hedging and different preferences for contract maturity meet in the swap market. The use of foreign exchange swaps results in a reduction of the total foreign exchange rate risk in the financial system.

Counterparty risk in foreign exchange swaps requires posting of margin

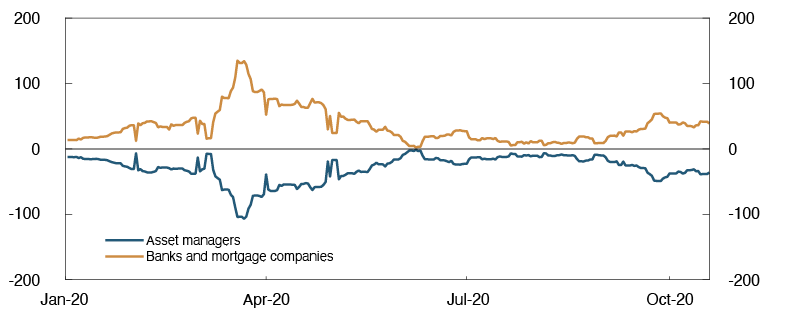

Foreign exchange swaps generally require margin to be posted for the duration of the contract in order to reduce counterparty risk. With a fixed agreed future exchange rate, unexpected exchange rate movements will result in a gain on the contract for one party and a loss for the other. The party with the gain on the contract will typically want security to ensure that the counterparty fulfils the contract. When the krone weakened markedly in mid-March, asset managers’ unrealised losses on foreign exchange swaps rose (Chart 1.B). Given the sharp depreciation as observed in March, the increase in margin calls was correspondingly sudden.

Chart 1.B Increased margin calls in March2 Margin payments under foreign exchange swaps. In billions of NOK

Sources: DTCC and Norges Bank

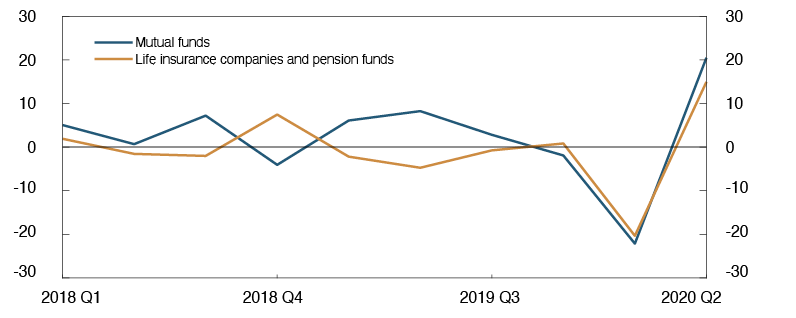

The increase in margin calls meant that asset managers needed to sell assets in order to obtain cash collateral (bank deposits). This led to selling pressure in the bond market (Chart 1.C) and a sharp rise in bond market risk premiums (Chart 2.1).

Chart 1.C Norwegian capital managers were heavy sellers of bonds in March3 Norwegian capital managers’ net purchase/sale in the Norwegian bond market. In billions of NOK

Source: Statistics Norway

Rebalancing of foreign currency hedging in the event of movements in the equity market can influence the krone exchange rate

Asset managers’ investment mandates often include requirements for currency hedging of a certain proportion of their foreign investments, and they adjust this hedging to the market value of investments. But if, for example, the value of foreign equities falls, the asset manager is overhedged relative to the targeted hedging ratio and will seek to rebalance the original currency hedge. This is done by repurchasing foreign currency in an amount equivalent to the fall in the equities’ value.

Under normal market conditions, rebalancing takes place if the hedging ratio deviates considerably from the target, or otherwise around month-end. When equity prices moved substantially and quickly in March, some managers opted to rebalance daily to prevent their hedges from falling too far out of sync with the value of foreign assets. Rebalancing associated with the fall in foreign equity prices contributed to the krone depreciation in mid-March (Chart 1.D), because asset managers sold NOK and bought foreign currency. This further increased margin calls on existing foreign exchange swaps. The fall in foreign equity prices thus also indirectly contributed to the sale of bonds in the Norwegian market and a rise in domestic risk premiums.

Chart 1.D Rebalancing owing to the fall in equity prices fuelled the krone depreciation4 Global equity indexes (S&P) and import-weighted exchange rate index (I-44, inverted)

Source: Bloomberg

Demand for bonds eventually picked up when banks were supplied with extraordinary F-loans from Norges Bank, and the Bank’s collateral requirements for loans to banks were eased. Asset managers’ need to obtain more liquid assets was also dampened when the market for NOK stabilised. With fewer sellers and more buyers in the market, bond market risk premiums declined.

Market participants must be prepared for increased margin calls when markets move

Liquidity risk associated with margin calls can be mitigated in various ways. Counterparty agreements can be made more flexible, eg by permitting different forms of collateral. In addition, an expanded network of repurchase agreements may provide greater security for access to liquidity under stress. Market participants themselves have an interest in exploring possibilities for mitigating the liquidity risk they face. Reduced liquidity risk among individual market participants will reduce the systemic risk associated with fire sales of securities in the event of large movements in the krone exchange rate.

The large-scale margin calls on foreign exchange swaps in March are an example of risk associated with derivative contracts more generally. Problems similar to those observed in March can also arise among other market participants and in relation to other kinds of derivatives contracts. Norges Bank is working to improve its surveillance of the use of derivatives contracts in Norway. The system for mitigating counterparty risk via daily exchanges of margin is essential to financial stability and reduces the probability of negative tail events in financial markets. When the parties to a derivatives trade exchange margin, this mitigates the risk that solvency problems will spread in a crisis. One lesson from the global financial crisis in 2008 was the importance of mitigating counterparty risk.

1 Period: 1995 Q4 – 2020 Q2. Asset managers are money market mutual funds, other mutual funds, life- and non-life insurers, and pension funds.

2 Period: 1 January 2020 – 19 October 2020.

3 Period: 2018 Q1 – 2020 Q2. Net purchase and sale of bonds from mutual funds, life insurance companies and pension funds.

4 Period: 1 January 2018 – 5 November 2020.

Who may hold an account with Norges Bank?

Norges Bank sets terms and conditions for counterparties’ loans from and deposits with the central bank. Monetary policy counterparties have access to all central bank facilities. Other counterparties may obtain access to the standing facilities, or parts thereof, if this contributes to promoting the purpose of central banking activities.

The new Central Bank Act entered into force on 1 January 2020. Those who may hold an account with Norges Bank are called counterparties, and the Act specifies that terms and conditions for counterparty accounts must contribute to promoting the purpose of central banking activities: …to maintain monetary stability and promote the stability of the financial system and an efficient and secure payment system…1

The account terms and conditions are further specified in a regulation laid down by Norges Bank.2 The regulation distinguishes between counterparties based on their function in the financial system. Banks that actively participate in payment and credit services are defined as monetary policy counterparties. They are given full access to Norges Bank’s standing facilities (intraday deposits, intraday loans, overnight deposits and overnight loans) and market operations (F-loans and F-deposits). All other counterparties have more limited access.

Banks’ important function in the financial system gives them access to central bank facilities

Banks are the backbone of payment services. Most payments take place when bank deposits are transferred. In the case of payments between customers of the same bank, the transfer is posted internally at the bank in question. Payments between customers of different banks are settled when central bank reserves are transferred between banks’ accounts with the central bank. Central bank reserves are banks’ unrestricted deposits with the central bank. Central bank reserves are the generally accepted means for final interbank settlement. A bank is willing to accept customer deposits from other banks (a liability to the customer) because at the same time, central bank reserves in an equal amount (a claim on the central bank) are transferred to its account. This enables banks’ customers to use their deposits as means of payment to customers of other banks.

Banks also play a key role in credit provision. Banks lend by crediting the borrower’s bank account with the amount of the loan. Thus, banks create their own financing, bank deposits, where the financing cost is equal to the interest the bank must pay on the customer’s deposits. Credit provision entails maturity transformation because loans typically have longer maturity than bank deposits, which are available immediately.

Banks’ key role in payment services and credit provision expose banks to liquidity risk. Banks that lose customer deposits must transfer an equivalent amount of central bank reserves from its account with the central bank to other banks’ central bank accounts. Banks therefore have the right to borrow reserves from and deposit reserves with the central bank throughout the day and overnight. They may also participate in central bank market operations.

Corresponding to banks’ need for central bank reserves is the ability of the central bank to influence interest rates in the economy by setting the terms for banks’ loans from and deposits with the central bank. Central bank reserves are the means by which the liquidity management system implements monetary policy and ensures an efficient payment system. The operational objective of the central bank’s liquidity policy is to keep short-term money market rates close to the policy rate. Norges Bank uses a quota system in its liquidity management. Banks receive interest on their deposits at the policy rate up to a certain quota, while deposits in excess of the quota bear lower interest (reserve rate).3 The quota system gives banks an incentive to demand the quantity of central bank reserves the central bank wishes to offer, at the same time as the desired interest rate is established in the market in the manner intended. Moreover, the quota system makes possible a transaction-based overnight interest rate, a desired characteristic of a reference rate (see "Libor to be replaced by new reference rates").

For financial stability considerations, other counterparties may have access

In the interest of an efficient payment system and financial stability, counterparties other than monetary policy counterparties may have access to a central bank account and Norges Bank’s standing facilities, or parts thereof. For example, central counterparties (CCPs) hold an account with Norges Bank. CCPs interpose themselves between the buyer and seller of financial instruments and guarantee that the contracts are fulfilled. Furthermore, CLS Bank International holds an account with Norges Bank. CLS Bank is an international settlement bank for foreign exchange transactions.

Other counterparties do not contribute to redistributing central bank reserves overnight or to quoting the overnight rate. With regard to the purposes of central banking activities, they make a particular contribution to an efficient payment system and financial stability, and less to the implementation of monetary policy. Other counterparties primarily only have access to intraday facilities.4 Access to the overnight facilities may disrupt Norges Bank’s liquidity management and its implementation of monetary policy.

1 Central Bank Act. Act relating to Norges Bank and the monetary system, etc.

2 Regulation on access to lending and deposit facilities at Norges Bank, which also entered into force on 1 January 2020.

4 See Financial Infrastructure Report 2019 for a further discussion of central counterparties and CLS Bank.

2 Bank funding

Banks’ access to funding deteriorated sharply in March. Norges Bank implemented extensive measures to improve liquidity, and risk premiums have fallen back to pre-pandemic levels. Norwegian banks now have ample access to funding and satisfy liquidity requirements. Looking ahead, the phasing-out of Libor will have consequences for bank funding.

2.1 Bank funding in a turbulent market

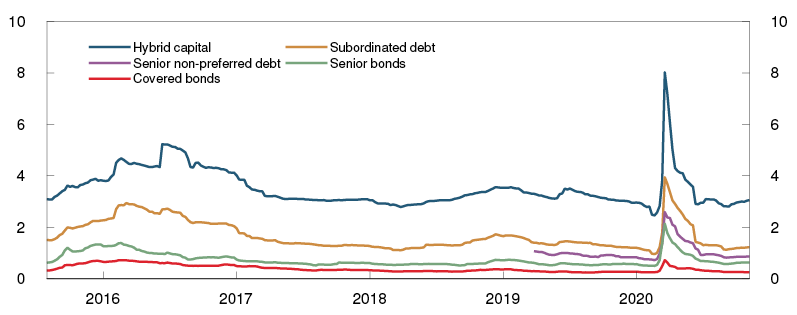

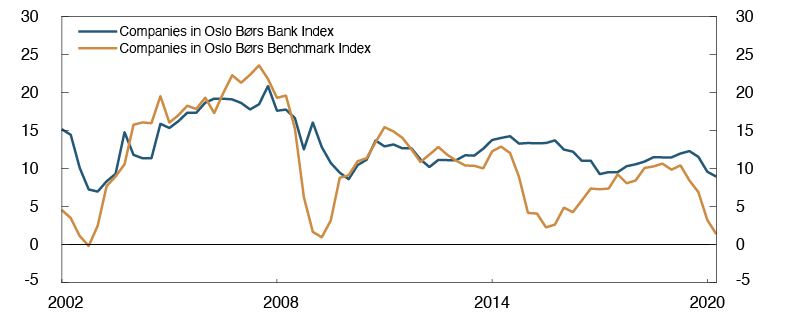

In March, there was considerable financial market volatility in connection with the outbreak of Covid-19. Premiums in the Norwegian money market rose sharply up to mid-March, in pace with increasing uncertainty and higher premiums in the US money market. Risk premiums on banks’ long-term wholesale funding also rose markedly (Chart 2.1), and banks’ access to such funding was reduced.

Chart 2.1 Risk premiums on banks’ long-term wholesale funding rose markedly in March1 Risk premiums in the Norwegian bond market. Five-year maturity. Percentage points above three-month Nibor

Source: Nordic Bond Pricing

Financial market turbulence also significantly affected market participants outside the banking system. When the krone depreciated markedly in March, asset managers faced a correspondingly abrupt increase in margin calls (see "Asset managers faced liquidity stress during the foreign exchange market turbulence in March"), which they met by selling securities, and selling pressure arose in the bond market. This led to a deterioration in Norwegian bond market liquidity and put further upward pressure on risk premiums on banks’ wholesale funding..

Norges Bank’s measures improved banks’ access to wholesale funding

Norges Bank implemented a number of measures to improve market liquidity and to ensure that the policy rate passed through to money market rates and banks’ lending rates. Since 13 March, Norges Bank has offered extraordinary NOK F-loans with longer-than-normal maturities. The F-loans are fully allotted at the announced floating interest rate. Collateral requirements for these loans will be the same as for ordinary F-loans. Because of high US dollar funding premiums, which is the result of high US dollar demand in global financial markets, temporary liquidity arrangements were also established between the Federal Reserve and a number of central banks, including Norges Bank. Through the arrangement, Norges Bank lent USD against the same type of collateral as lending in NOK.2

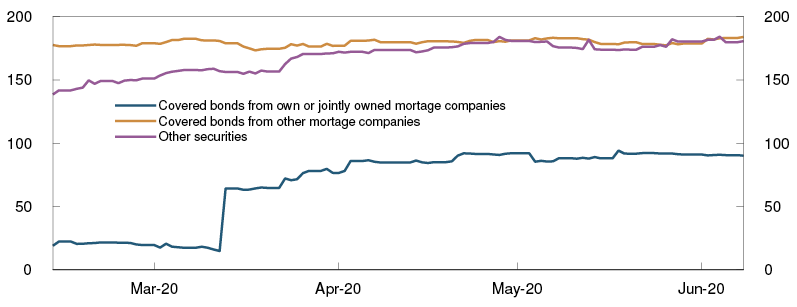

To increase banks’ eligibility for these loans, the guidelines for pledging collateral in Norges Bank were also temporarily relaxed. In particular, the ability to pledge up to 100% of the volume outstanding of a security increased the amount banks could borrow from the central bank. In March and April, banks’ holdings of Norwegian securities increased by over NOK 100bn, primarily owing to banks’ purchases of covered bonds issued by their own mortgage companies (Chart 2.2) in order to pledge them as collateral for loans from Norges Bank. An announced partial reversal of the relaxation of the guidelines for pledging collateral will commence in February 2021.

Chart 2.2 Banks’ holdings of securities increased in March and April3 Norwegian banks’ securities holdings. In billions of NOK

Source: VPS

The extraordinary measures by central banks and other authorities, both abroad and in Norway (see Annex), contributed to the pickup in financial market liquidity and the narrowing of risk premiums. Selling pressure from asset managers eased when the krone stabilised and the substantial decline in the value of foreign investments abated. Through spring and summer, banks’ ability to obtain funding in the bond market has improved significantly, and risk premiums on banks’ wholesale funding have come down to pre-crisis levels (Chart 2.1). Norges Bank’s semi-annual survey of liquidity in the Norwegian bond and short-term paper market confirms this picture.

Banks were better equipped to address the turbulence than during the global financial crisis

Stricter Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) requirements for banks following the financial crisis helped to better equip Norwegian banks and mortgage companies to address financial market turbulence. The NSFR reduces long-term refinancing risk. The NSFR has remained unchanged in recent quarters and is above the minimum requirement.4 The LCR allows banks to meet their obligations through periods of limited access to new funding. In 2020 Q1, the total LCR fell somewhat for Norwegian large and medium-sized banks, but the LCR still remained well above the minimum requirement. At end-Q2, the LCR increased again. Because of the extraordinary liquidity measures by the central bank when the markets were stressed, banks did not sell securities from liquidity reserves, but instead pledged more securities as collateral for loans from Norges Bank. This helped prevent a further tightening of banks’ funding markets.

1 Period: Week 32 2015 – week 45 2020. Premiums on bonds issued by large banks and mortgage companies in the Norwegian market.

2 With an additional haircut for foreign exchange risk.

3 Period: 13 February 2020 – 8 June 2020. The sample comprises Norwegian banks that report on a consolidated basis under CRD IV.

4 The Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) has been adopted by the EU, but has not yet been transposed into Norwegian law. Nevertheless, Norwegian banks have reported their NSFRs for several years.

2.2 Structure of Bank funding

Bank funding is diversified

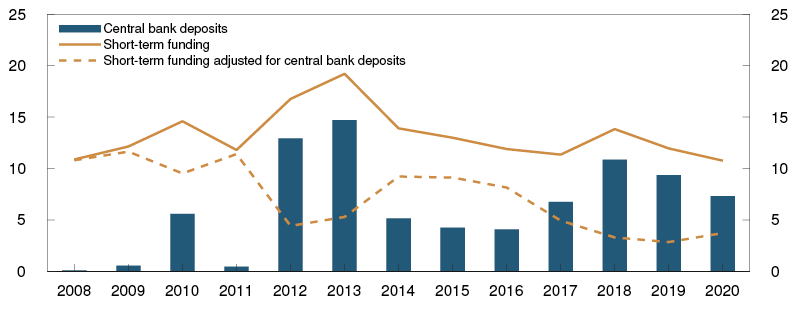

Compared with the financial crisis in 2008, Norwegian banks were less affected by the turmoil in the US market in spring 2020. A larger share of banks’ short-term USD funding is now invested in safe, liquid assets, such as central bank deposits. The share of short-term foreign currency funding not placed in central banks has declined in recent years and is now approximately 4% of total assets (Chart 2.3).

Chart 2.3 Share of short-term foreign currency funding not placed in central banks has declined in recent years5 Short-term funding and central bank deposits in foreign currency. Norwegian banks. Share of total assets. Percent

Source: Norges Bank

Bank funding is diversified and together with customer deposits, bonds and short-term paper represent the most important funding sources for Norwegian banks. Customer deposits, which account for around 40% of bank funding, have remained stable since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. In December 2019, Finanstilsynet (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway) issued requirements for eight Norwegian banks’ own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL) that can quickly be written down and converted to new equity. These banks are considered so important to the financial system that they will not be wound up if they were to fail. This will result in more efficient resolution without recourse to taxpayer funds (see "New debt category for norwegian banks will make resolution more efficient"). The requirement is to be met in part by a new category of liabilities in the form of subordinated debt, which is lower in priority than senior debt. At the end of October, six out of eight banks had issued approximately NOK 17bn in subordinated debt. However, until 1 January 2024, senior debt may also be used to meet the requirement.

Ample liquidity has made it possible for banks to offer liquidity support to customers and defer principal payments. This is important because many businesses are suffering a sharp fall in revenue, many employees have been furloughed and Norwegian households have large mortgages. However, substantial drawdowns on credit and liquidity facilities could increase banks’ funding needs. Drawdowns on such facilities have not been substantial so far.

New debt category for norwegian banks will make resolution more efficient

Failing banks that are too important to be wound up must have liabilities that can quickly be written down and converted to new equity. Finanstilsynet (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway) has set the amount of such liabilities that each of these banks must have. From 2024, all such liabilities must be lower in priority than senior debt. In 2020, some Norwegian banks have issued such bonds, which may increase their funding costs somewhat, at least in the short term.

Banks must issue subordinated debt to meet the minimum requirement for eligible liabilities

The efficient resolution of a failing bank should be possible without recourse to taxpayer funds. The bank must therefore have sufficient regulatory capital and liabilities that can be written down and converted to new equity, also referred to as a bail-in. The minimum requirement for such capital and liabilities is called MREL (Minimum Requirement for own funds and Eligible Liabilities).

In December 2019, Finanstilsynet decided that the eight most important Norwegian banks were to be subject to MREL1. The requirement is to be met using own funds and a new debt category in the form of subordinated debt, ie debt that ranks above other subordinated debt but below senior debt. Up until 1 January 2024, the requirement can also be fulfilled with senior debt that is issued before 1 January 2020 and that would otherwise fulfil the requirements for eligible debt. To comply with the priority ranking requirement, banks must replace maturing ordinary senior debt with subordinated debt before 2024. It is expected that these banks as a whole will need to issue approximately NOK 200bn worth of subordinated debt by 2024 to comply with the requirement. At end-2019, these banks’ senior bonds totalled slightly more than NOK 600bn, and the requirement can be met by replacing 1/3 of this debt with subordinated debt.

Issuance of subordinated debt may increase banks’ short-term funding costs somewhat

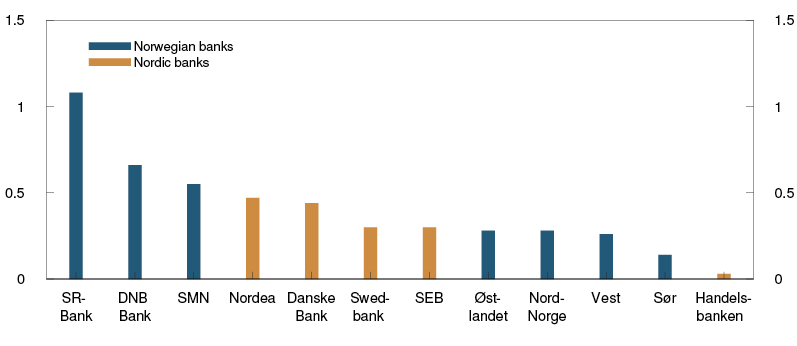

At the end of October 2020, six of the eight banks2 have issued around NOK 17bn in subordinated debt. Through October, the risk premium above three-month Nibor for the subordinated bonds issued by Norwegian savings banks was 0.88 percentage point.3 This is not more expensive than what other Nordic banks have paid in the NOK market. Subordinated debt is more expensive than senior debt at the same maturity. For the largest Norwegian savings banks, the risk premium for senior debt was 0.65 percentage point above three-month Nibor.

Banks’ funding costs may increase somewhat, at least in the short term, since the risk premium on new subordinated debt is higher than on senior bonds, and the risk premium on senior debt outstanding is fixed until maturity. However, the risk premium on senior debt may fall when banks issue bonds that are to absorb losses prior to senior debt. However, any fall in premiums on senior debt will not contribute to lower funding costs until existing senior debt matures and banks issue new senior debt.

New regulatory framework for subordinated debt

The EU has adopted a new regulatory framework for MREL. It differs somewhat from the current Norwegian rules, particularly the priority ranking requirement. The new rules are to be incorporated into the EEA Agreement and implemented in Norwegian law. A proposal for how this is to take place has been circulated for comment by the Ministry of Finance, with a consultation closing date of 6 January 2021.

1 DNB, Sparebank 1 SR-Bank, Sparebanken Vest, Sparebank 1 SMN, Sparebanken Sør, Sparebank 1 Østlandet, Sparebank 1 Nord-Norge and Bank Norwegian.

2 All excluding DNB, Bank Norwegian and Sparebank 1 SR-Bank.

3 Risk premium values are indicative credit spreads above three-month Nibor for generic five-year debt in NOK. In practice, maturity of issued subordinated debt is five years. Source: Nordic Bond Pricing.

Risk posed by banks’ substantial covered bond exposures

Covered bonds are an important source of long-term funding for banks. At the same time, covered bonds account for almost 50% of banks’ liquidity reserves in NOK. This share has remained stable in recent years but declined slightly so far in 2020 owing to an increase in central bank deposits. If funding dries up and many banks are forced to liquidate large covered bond holdings at the same time, the value of banks’ liquidity portfolios could rapidly decline. Substantial selling pressure in the covered bond market may intensify liquidity problems as bank funding conditions tighten further. Banks’ substantial holdings of other banks’ covered bonds amplify the interconnectedness of financial institutions and may constitute a systemic risk.

High house prices also pose a risk to banks’ covered bond funding because a fall in house prices may result in a fall in covered bonds’ over-collateralisation below the regulatory requirement and possible investor and rating agency requirements. If over-collateralisation falls below such requirements, this may lead to higher risk premiums and poorer access to funding by residential mortgage lenders. In spring 2020, new covered bond issues that were larger than the increase in the cover pool, primarily residential mortgages, led to lower over-collateralisation among residential mortgage lenders. Nevertheless, over-collateralisation remains high.

The Libor phase-out will impact bank funding

By end-2021, the global reference rate Libor will be replaced by new reference rates for eg GBP and USD. The new reference rates are near risk-free overnight rates with properties that differ from Libor (see "Libor to be replaced by new reference rates"). Norwegian banks and mortgage companies raise more than half of their bond funding in foreign currency. Norwegian issuers of foreign currency bonds must be prepared for the transition to the new reference rates. The transition from Libor will also influence segments of the derivatives market, where banks and mortgage companies convert foreign currency funding to NOK.6 In combined interest rate and foreign exchange derivatives, which currently use Nibor as a reference rate, participants should be prepared to use the alternative reference rate Nowa.

5 Period: 2008–2020. Annual data at 30 June. Comprises deposits from foreign customers and central banks, and debt securities with less than 12 months’ residual maturity.

6 At end-2019, approximately 50% of bond funding was issued in foreign currency. Banks and mortgage companies that use cross-currency basis swaps for conversion to NOK may be particularly affected by the transition.

Libor to be replaced by new reference rates

Libor is being phased out, which will affect Norwegian market participants and may have consequences for Norway's most important reference rate, Nibor. If the transition to new reference rates occurs with market participants ill-prepared, it could pose a threat to financial stability. Nibor users must now be prepared to use the recommended alternative Norwegian reference rate, Nowa.

The market is transitioning away from Libor

In recent years, regulatory authorities in the UK and the US have worked towards phasing out the most important global reference rate, Libor. A reason for this, among others, is that confidence in Ibor rates has weakened in recent years.1 The expiration date for Libor is now fast approaching, and by end-2021, Libor will be replaced by new, alternative reference rates.

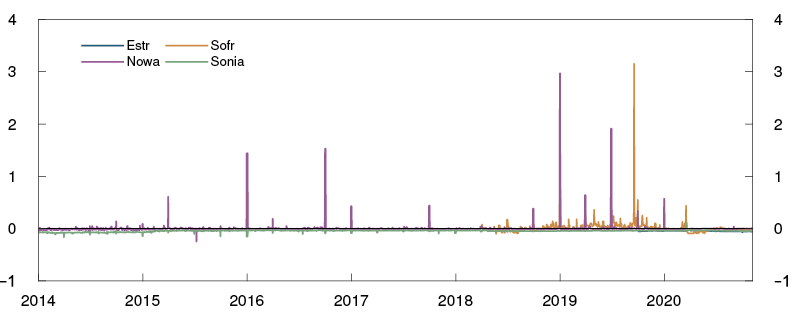

The new reference rates are overnight rates that are near risk-free. They differ from Libor in several ways. While Libor measures the interest rate on unsecured market funding for banks over a three-month period2, the new reference rates measure interest rates on overnight lending. Libor is therefore influenced by changes in credit and liquidity premiums on bank funding, while the new reference rates closely track the policy rate (Chart 2.A). The tenor differences between the rates also have consequences for the calculation of interest payments in contracts linked to interest rates.

Chart 2.A The new reference rates lie close to the policy rate3 Margin above the policy rate for new reference rates. Percentage points

Source: Bloomberg

The work of phasing in the new reference rates is currently intensifying globally. Norwegian market participants with exposures to Libor should be prepared to use the new international reference rates and be able to manage reference rates with characteristics that are different from Libor.

The market should prepare to use Nowa

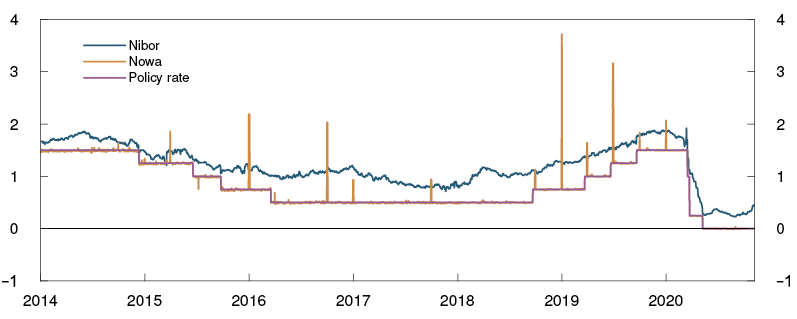

The global transition from Libor to new reference rates may have consequences for Norway's most important reference rate, Nibor. Like Libor, Nibor is a three-month rate with properties that differ from those of new reference rates being used abroad. As other countries increasingly transition to near risk-free overnight rates as their reference rates, market participants abroad may be less willing to be exposed to Nibor in derivatives, bonds and other financial contracts. Less use of Nibor may weaken interest in being a panel bank and increase the risk that Nibor will also need to be phased out in the future.

If the publication of Nibor were to end, banks and other Nibor users would need to be prepared to use the recommended alternative Norwegian reference rate, Nowa. Over the past year, two working groups consisting of representatives from the financial industry have worked towards facilitating the use of Nowa as a reference rate.4 The working groups have published recommended market standards for the use of Nowa in financial contracts and fallback solutions for replacing Nibor in existing contracts. The groups are also working to establish an interest rate derivatives market linked to Nowa, or overnight index swaps (OIS). This work is important for Nowa to function as a reference rate, and Norges Bank will continue to facilitate it by serving as the secretariat for the ARR working group5 and participating as an observer in other working groups.

In addition to the ongoing efforts of the working groups, necessary preparations for the use of Nowa must also be made by individual users. Since using Nowa also requires modifications to technical systems and contracts, work in this area should be intensified. Norges Bank will work to make Nowa easy to use and will publish a daily index for Nowa in order to simplify the calculation of interest payments in Nowa contracts.

It is up to users to decide which reference rate to use in their contracts. Nevertheless, Norges Bank encourages all Nibor users to make the preparations necessary for using Nowa.

The transition to new reference rates may create challenges

If Nowa were to replace Nibor as the reference rate in Norway, the different properties of the reference rates may have consequences for both users and how the market functions. The differing properties of the reference rates were highlighted as recently as during the market turbulence in March 2020, when a higher risk premium in Nibor caused Nibor to far exceed the expected policy rate. Nowa, on the other hand, followed the policy rate closely (Chart 2.B).

Chart 2.B Nowa and Nibor have different characteristics6 Nowa, three-month Nibor and the policy rate. Percent

Source: Norges Bank

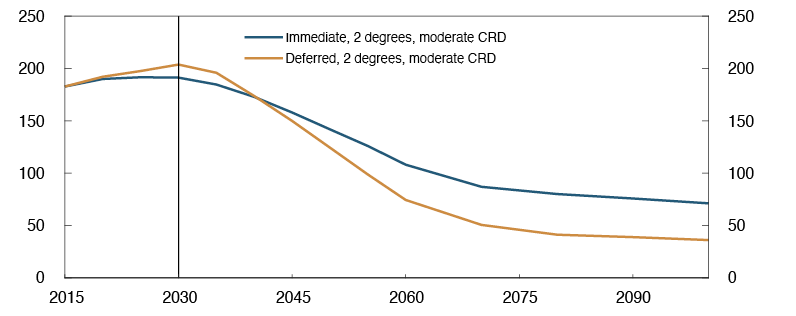

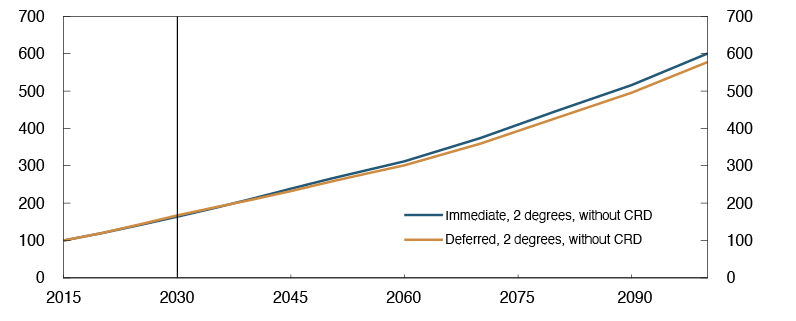

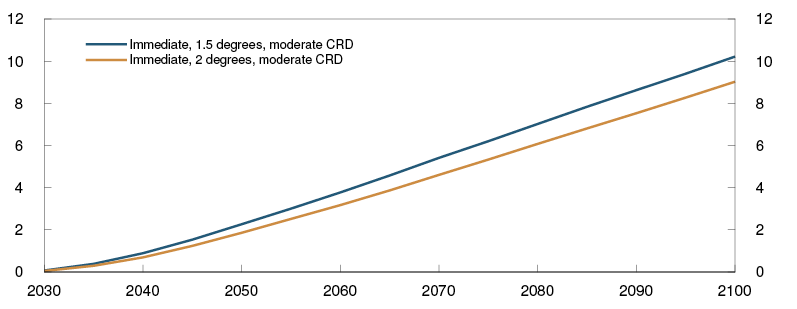

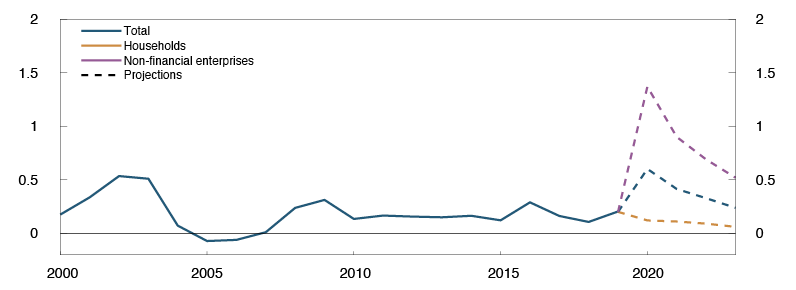

Banks may need to include wider and more volatile margins in their loan contracts if lending rates are linked to Nowa rather than to Nibor. Changes in the risk premiums that banks pay on their funding is currently captured by Nibor, which makes it easier for banks to price loans with a stable margin above Nibor. If lending rates were instead to be linked to a near risk-free reference rate, like Nowa, banks may need to adjust the margin they require above the reference rate in order to compensate for risk premium changes that are not captured by the reference rate. Wider and more volatile margins may reduce the predictability of borrowers’ interest expenses and decrease market transparency.