Executive Board’s assessment

If society is to function properly, its financial infrastructure must be well-functioning and enable payments. Norway has an efficient and secure payment system. Operations are stable and payments can be made swiftly at low economic cost and in ways that are adapted to users’ needs.

The threat landscape has worsened over time, however, and scenarios must be considered where even well-protected systems could become unavailable. Technological advances in financial market infrastructures (FMIs) are also occurring rapidly. Looking ahead, new services and new market entrants may challenge established systems and structures, such as mobile payments in shops, domestic and cross-border instant payments, new payment institutions and new payment arenas such as crypto markets. In addition, central settlement infrastructure also needs to be updated in order to meet future needs.

If Norway’s financial infrastructure is to remain efficient and secure, it must be developed further.

Cooperation with Nordic and European central banks provides the best long-term settlement system solutions

Norges Bank’s settlement system is the core of the Norwegian payment system. The system is efficient and stable, with reliable continuity solutions. At the same time, maintaining an efficient and secure settlement system becomes more demanding with stricter security and contingency requirements. The number of settlement service providers to choose from is limited. The other Nordic countries have joined or are considering joining TARGET, the Eurosystem’s settlement platform. Norges Bank also considers that cooperation with Nordic and European central banks will best serve the settlement system in the long term. Through cooperation, the settlement system will become better equipped to ensure stable operations, protect against attacks and further develop new functions and services. In January 2025, Norges Bank initiated formal discussions with the European Central Bank (ECB) on Norwegian participation in T2. T2 is the core system for settling payments in TARGET services, with functionality similar to Norges Bank’s current settlement system. A final decision will be made once necessary clarifications have been addressed.

A well-functioning system for instant payments is a key component of an efficient payment system. In November 2024, Norges Bank signed an agreement with the ECB on Norwegian participation in TARGET Instant Payment Settlement (TIPS). This means that Norges Bank will use the Eurosystem’s technical platform to settle instant payments, which paves the way for new services such as cross-currency instant payments and new domestic instant payment services.

Even if Norges Bank participates in both T2 and TIPS, it will still be responsible for central bank settlement in NOK. At the same time, participation in the pan-European settlement platform ensures that the Norwegian settlement system is developed to the same extent as in Nordic and European countries.

National control of the payment system must be sufficient

National control means that the authorities have sufficient control capability and freedom of action to maintain critical functions, even in the event of crises or conflicts. Norges Bank is tasked with promoting a secure payment system and contributing to contingency arrangements. A key part is continuously assessing necessary measures for maintaining sufficient national control of critical payment system functions. This must be monitored systematically and in a scheduled manner. Norges Bank will engage in dialogue on this matter with the Ministry of Finance, Finanstilsynet (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway) and the financial industry.

National control also involves international cooperation. Key payment system functions and services, such as cross-border payments and FX transactions, are essentially international. International cooperation and contributions from experts in other countries can strengthen the operation of and developments in the Norwegian payment system. In some crisis scenarios, available operational or contingency arrangements in other countries can help maintain critical functions in Norway.

Payment system contingency arrangements must be enhanced

The security and contingency arrangements of individual entities are the payment system’s first line of defence. Each entity is responsible for implementing necessary measures based on an assessment of vulnerability and risk. Given the current heightened threat landscape, the possibility that even well-protected systems could become unavailable must be taken into account. To be able to handle such serious situations, contingency arrangements must be enhanced.

A working group appointed by the Ministry of Finance has recently published a report with recommended measures to enhance contingency arrangements in the digital payment system. A number of the measures have also been recommended by the government-appointed Payment Commission. Enhancing contingency arrangements for point-of-sale (POS) payments by expanding the backup solution for BankAxept and establishing an independent backup solution for basic banking services are measures that could have a significant impact on overall contingency arrangements. However, contingency arrangements will not be enhanced until the measures have been implemented. Norges Bank has initiated a process to establish an independent backup solution for its settlement system and will contribute in following up other recommendations in collaboration with the Ministry of Finance, Finanstilsynet and the financial industry.

Enhancing contingency preparedness among the general public and at points of sale is also needed. Sound contingency arrangements among the general public reduce vulnerability for both individuals and the payment system as a whole. Consumers should have alternative means of payment available, including multiple types of payment cards, accounts with different banks and cash. Merchants should make sure that they are able to accept different forms of payment, even when their ordinary cash register systems fail.

The provision of cash services is vulnerable

The vast majority of payments are made digitally, and a secure and efficient payment system is primarily ensured through robust digital solutions. However, even though cash usage is low, cash still plays an important role in the payment system. Cash is crucial for contingency considerations and is the only way to make payments in the event of a complete failure of electronic payment systems. Furthermore, cash is important for individuals who do not have the skills or opportunity to use digital payment solutions.

For cash to fulfil its functions, it must be available and easy to use for the general public and the business sector. Consumers’ right to pay using cash has been strengthened, which is important for ensuring that cash can continue to fulfil its functions. Moreover, Norwegian banks have a legal obligation to ensure satisfactory cash services for their customers in both normal and contingency situations.

However, the provision of cash services today is vulnerable and has certain weaknesses. Most cash handling services are carried out by non-bank entities. Banks’ obligations apply regardless of a well-functioning service provider market, and banks must therefore be prepared to step in and find other solutions to maintain an adequate supply if these entities reduce their services.

Mobile payments must include various payment channels

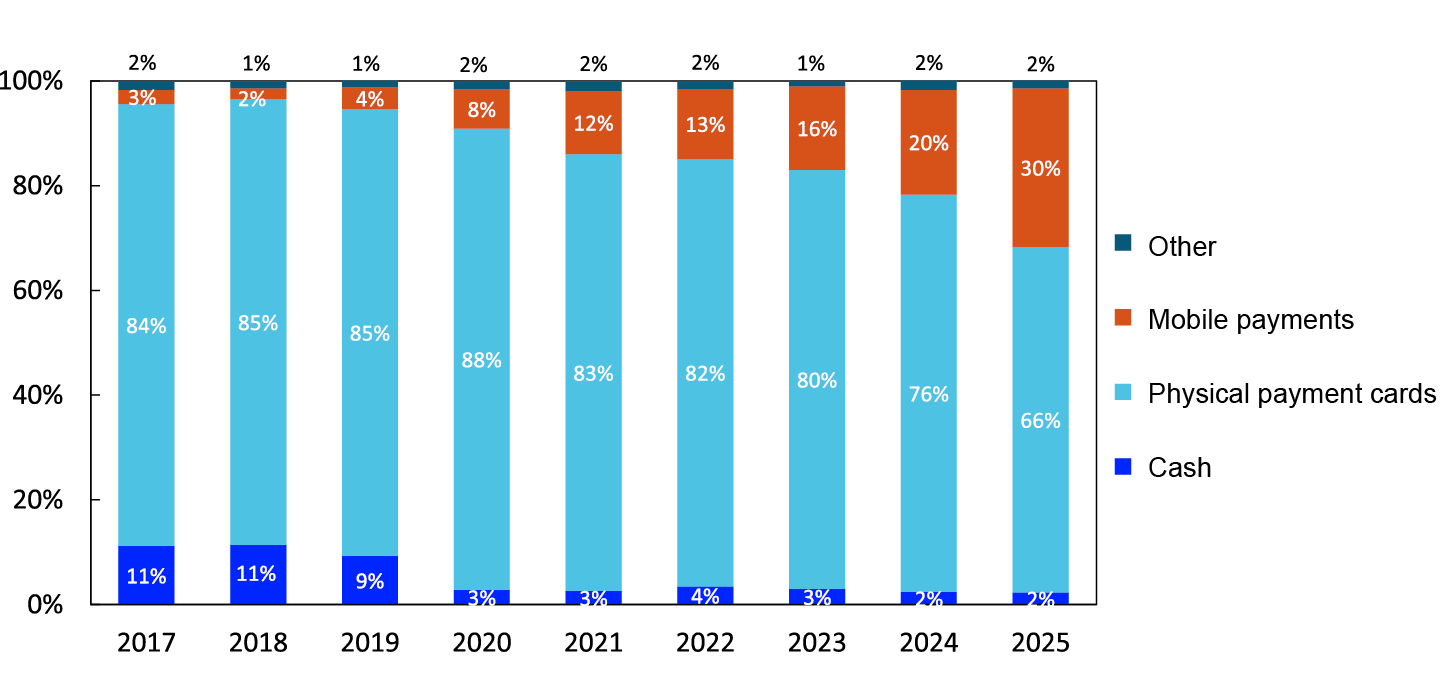

Mobile payments are rising rapidly and now account for three out of ten payments at physical points of sale (POS). Having the opportunity to choose to pay with a mobile phone is beneficial for users. The extensive use of new mobile payment services indicates that users find them efficient and secure.

Different payment cards and various types of bank transfers should be available as underlying payment solutions to promote competition, cost efficiency and contingency preparedness. For national security considerations, it is particularly important that BankAxept is an available alternative.

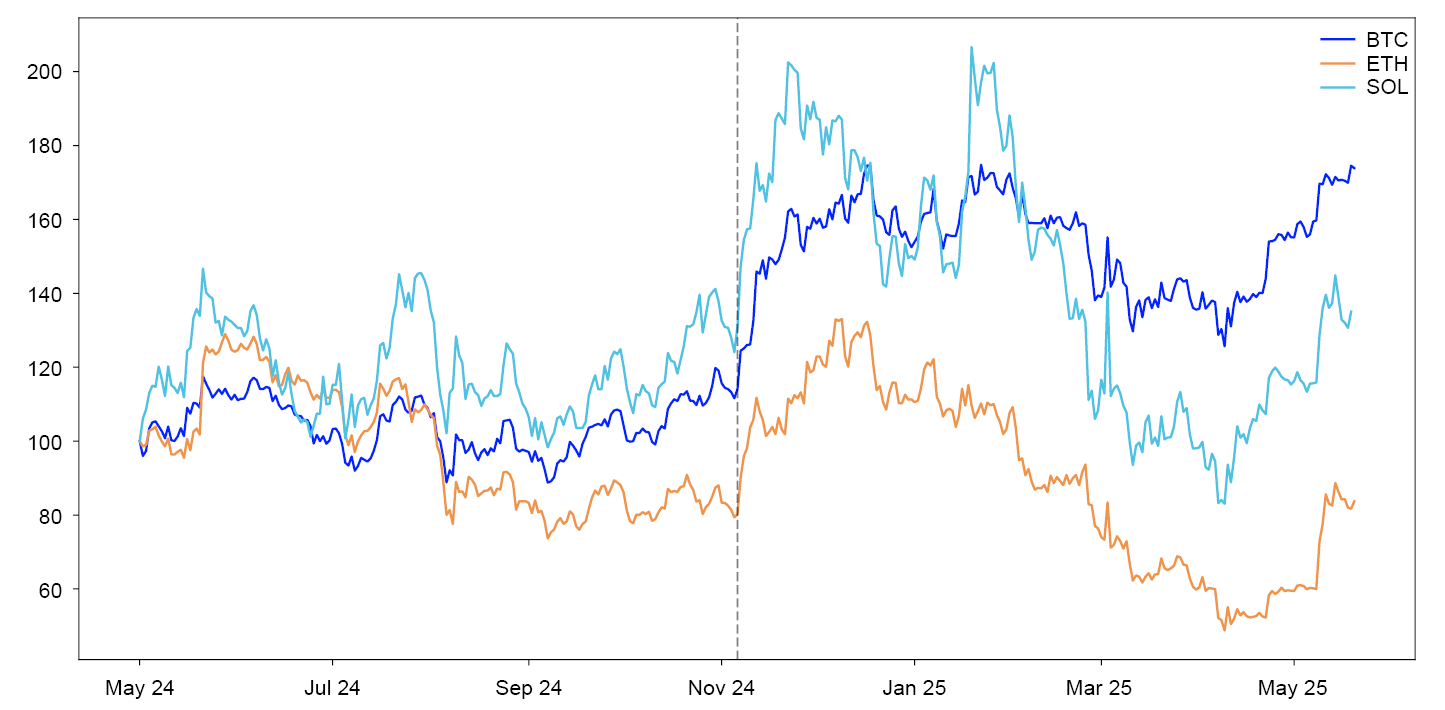

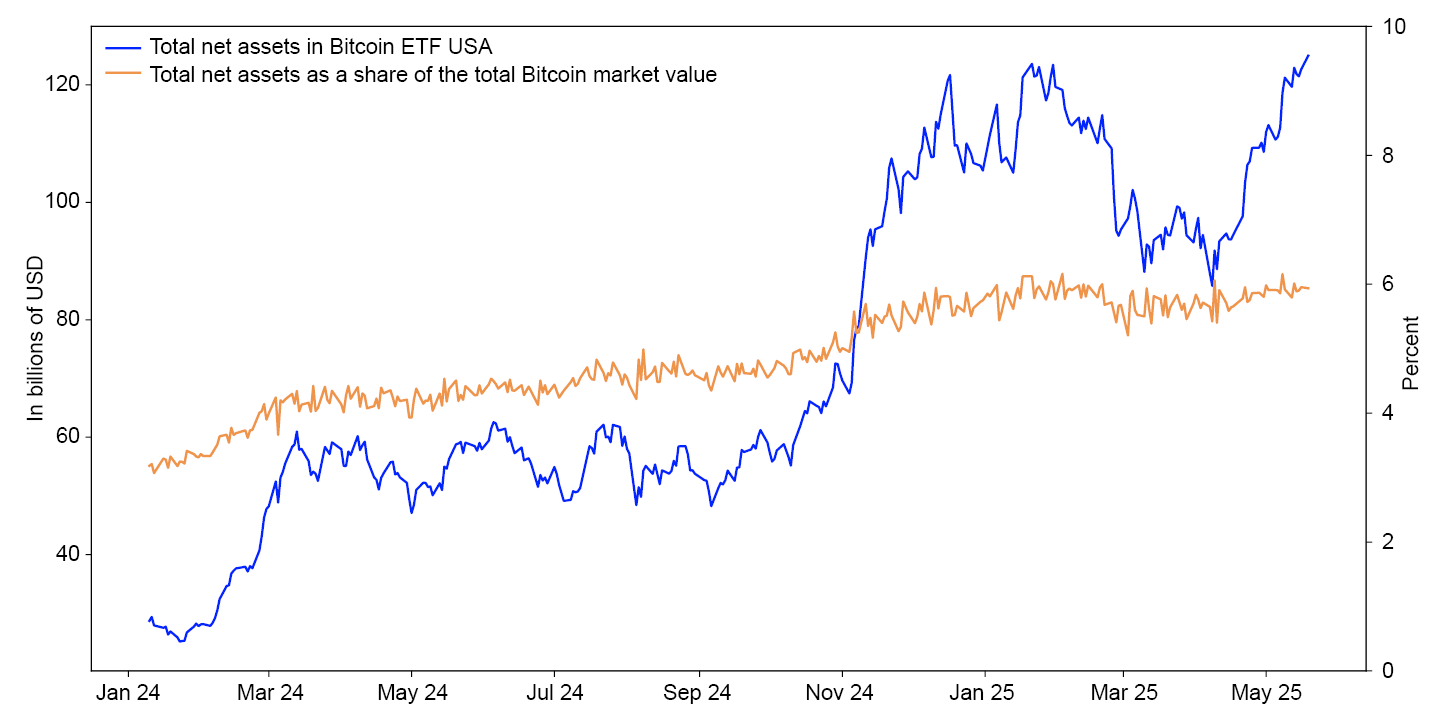

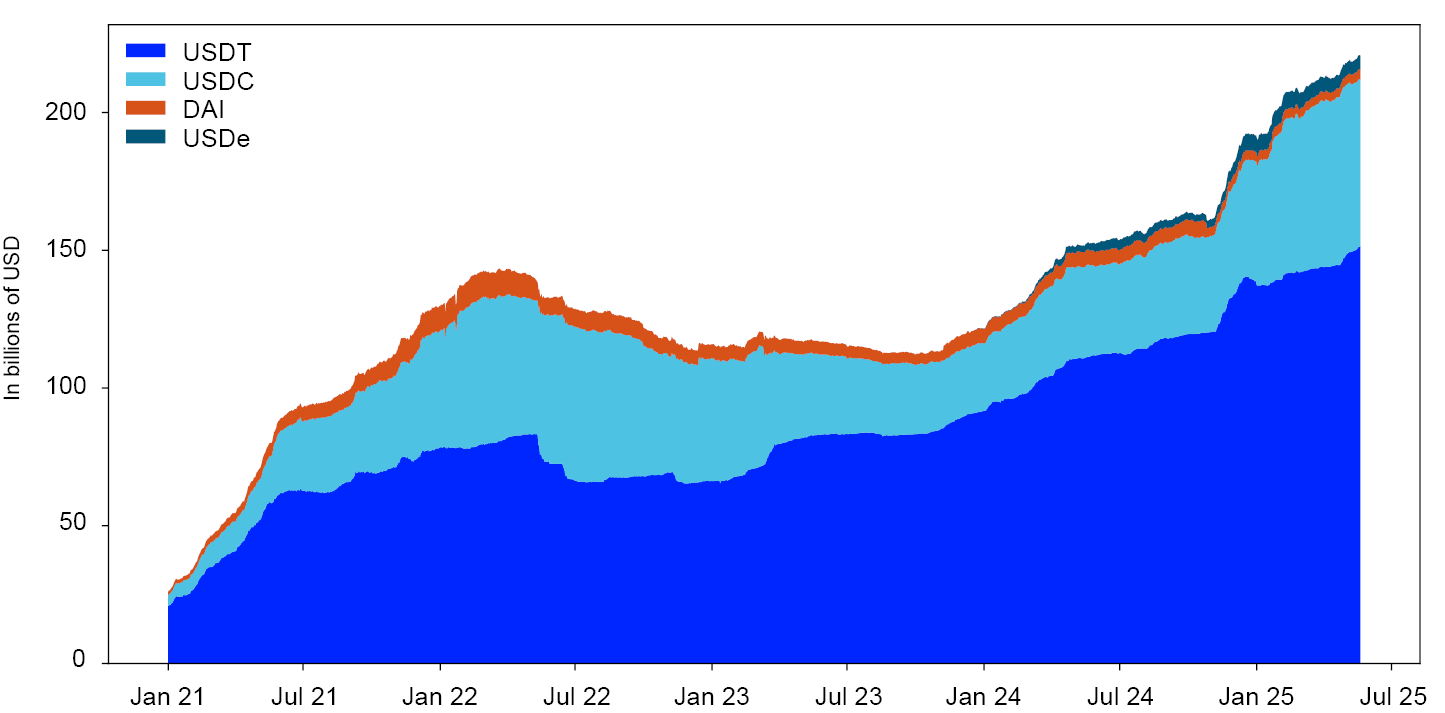

Potential systemic risk from cryptoassets must be mitigated

Based on market size, cryptoassets do not pose a threat to financial stability today. At the same time, there are signs of closer interconnections between cryptoasset markets and the traditional financial system internationally. Among other things, this includes cryptoassets packaged into traditional financial instruments, which can be combined with leveraging. This makes cryptoassets more accessible to investors. Stablecoins are emerging and are often backed by traditional financial assets. Such interconnections can be a source of systemic risk. New US regulation of stablecoins and other cryptoassets may contribute to volume growth and increased systemic risk ahead. The EU’s new Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCAR), which will also be transposed into Norwegian law, helps counter overall systemic risk from cryptoassets. However, MiCAR does not cover all sources of systemic risk. Regulatory developments will be necessary to counter both systemic risk and threats to the functionality of the monetary and payment system stemming from the emergence of cryptoassets.

Tokenisation is worth looking into

Norges Bank is assessing whether a central bank digital currency (CBDC) is an appropriate instrument to ensure access to a means of settlement trusted by all, even in new payment arenas, and whether a CBDC will facilitate responsible innovation and improve payment contingency arrangements. In addition to retail CBDCs, used by the general public, the Bank is researching wholesale CBDCs to be used as a means of settlement between banks and others with an account at the central bank. Tokenisation in payment and financial systems has received increasing attention in the ongoing phase of Norges Bank’s CBDC research. Tokenisation is a process in which an asset is represented as a digital unit – a token – on a ledger based on distributed ledger technology (DLT). Tokenisation may streamline the financial infrastructure but also entails risk. Facilitating settlement in central bank money can contribute to more efficient and secure transactions in tokenised assets, such as tokenised bank deposits. Norges Bank is currently conducting experimental testing of technology related to tokenisation and central bank settlement. This phase of Norges Bank’s study is scheduled to be completed in 2025.

The Executive Board

28 May 2025

1. An efficient payment system

The Norwegian financial infrastructure is efficient and stable. Payments can be made swiftly and safely at low economic cost. Important milestones have recently been reached in the further development of the infrastructure.

Today’s Norwegian infrastructure is among the most digitalised in the world, with stable operations and few disruptions. Payment methods have undergone major changes in recent years and developments are progressing at a rapid pace. This section discusses some of the main aspects of payment operations and the recent development of key components in the financial infrastructure.

Norges Bank’s settlement system

Norges Bank’s settlement system (NBO) is the core of the Norwegian payment system, and all electronic payments made in NOK are ultimately settled between banks in this settlement system. Norges Bank is the operator of NBO.

The current settlement system is efficient, and operations were stable through 2024 without material deviations. Daily settled payments averaged NOK 350 billion. At the end of 2024, banks had NOK 38 billion in deposits at Norges Bank.

Technological advances and changes in the settlement systems in Norway’s neighbouring countries have made it necessary to initiate work on the next generation settlement system in Norway. In February 2025, Norges Bank announced the commencement of formal discussions with the European Central Bank (ECB) to address remaining clarifications surrounding Norwegian participation in the Eurosystem’s settlement platform, T2. In 2024, Norges Bank decided to establish a new service for instant payments in NOK, and on 28 November the Bank signed an agreement with the ECB to use the Eurosystem’s instant payment platform: TARGET Instant Payment Settlement (TIPS). Norges Bank’s work on the next generation settlement system is discussed in more detail in “Next generation settlement system”.

An important milestone in the further development of the settlement system is the transition to the new ISO 20022 payment messaging standard. The standard was implemented for gross payments in March 2025 and will also be used for net payments in NBO by the end of November 2025. The messaging format that will be used in NBO ahead has been developed in collaboration with the banking industry, the central banks of Sweden and Iceland and settlement system service providers. The transition to ISO 20022 was carried out simultaneously for the settlement systems in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. The format opens up for payment messages with more detailed information than before and facilitates cross-border standardisation across different FMIs. For more details on NBO, see Norges Bank’s settlement system - Annual Report 2024.

Norwegian interbank clearing system

The Norwegian interbank clearing system (NICS) is the banks’ joint system for receiving and clearing interbank payment transactions before they are settled with finality in NBO. Norges Bank has awarded the licence to operate NICS to the financial industry’s infrastructure company Bits AS (Bits), and Norges Banks supervises NICS.

NICS’ operations are stable, with a high degree of availability. There were two severe operational disruptions in NICS in 2024, but the incidents were resolved, and settlement was completed the same day. In 2024, daily settled payments in NICS averaged NOK 405 billion.

Bits has entered into an agreement with Mastercard Payment Services Infrastructure (Norway) AS (MPSI) for the technical operation and management of NICS. Bits is the system owner and is responsible for the system, including the parts outsourced to MPSI. In 2024, MPSI took over full responsibility for NICS operations from Nets, which has operated NICS for several years. Norges Bank imposed conditions for this transition. For example, the physical infrastructure, including data centres, local network infrastructure and similar components, will remain in Norway. In addition, a contingency arrangement including physical infrastructure has been established in Sweden.

Securities settlement and central counterparties

Securities settlement in NOK involves the delivery of securities in accounts at the central securities depository (CSD) and payments made via designated accounts in NBO. To eliminate settlement risk, the seller’s transfer of securities is coordinated with the buyer’s payment through the systems of Norges Bank and the CSD. The Norwegian CSD is operated by Euronext Securities Oslo (ES-OSL). At the end of 2024, the total value of registered securities amounted to NOK 8 020 billion and the number of investor accounts stood at 1 601 089.

ES-OSL is part of a corporate group that includes several other CSDs. Euronext is undertaking a modernisation project aimed at increasing harmonisation across different CSDs and jurisdictions. The solution under development is designed to align with the ECB’s securities settlement platform, T2S. In collaboration with other authorities and the banking industry, Norges Bank is planning to initiate an assessment of potential participation in T2S for the settlement of securities transactions in NOK. This will entail dialogue with other authorities and the financial industry.

In Norway, as in other countries, securities settlement takes place a few days after the trade is agreed upon. To protect against potential counterparty issues during the period leading up to settlement, many trades are settled through a central counterparty (CCP). 1 This applies, for example, to all equity trades on Oslo Børs. The use of CCPs results in positions that must be settled in the Norwegian securities settlement system.

The CCPs most commonly used by Norwegian participants are Cboe Clear Europe (CCE), SIX x-clear, Euronext CCP and LCH Ltd, of which the latter is particularly widely used. In April 2024, the EU adopted an amendment to the regulation to reduce the EU’s dependence on third country CCPs, such as in LCH Ltd in the UK. One of the amendments requires major market participants to use CCPs domiciled in the EU. 2 For the time being, only the largest Norwegian participants will be comprised by the requirements.

FX settlement

In an FX transaction, the parties exchange two currencies with each other. This market is dominated by the largest international banks. In a traditional FX settlement, there is a risk that the counterparties may fail to fulfil their part of the agreement. To reduce the risk associated with FX settlement, the US FX settlement bank CLS was established in 2002, and this bank currently settles FX transactions in 18 currencies3. CLS holds an account at Norges Bank for the settlement of FX transactions involving NOK.

In 2024, banks’ daily trades averaged NOK 832 billion, of which cleared payment obligations to CLS amounted to an average of NOK 25 million (purchased NOK less sold NOK).

CLS has delivered highly reliable services for many years. Due to technical upgrades and the addition of new settlement member banks in recent years, the number of disruptions among CLS participants has increased, but this trend now appears to have been reversed.

Electronic retail payment services

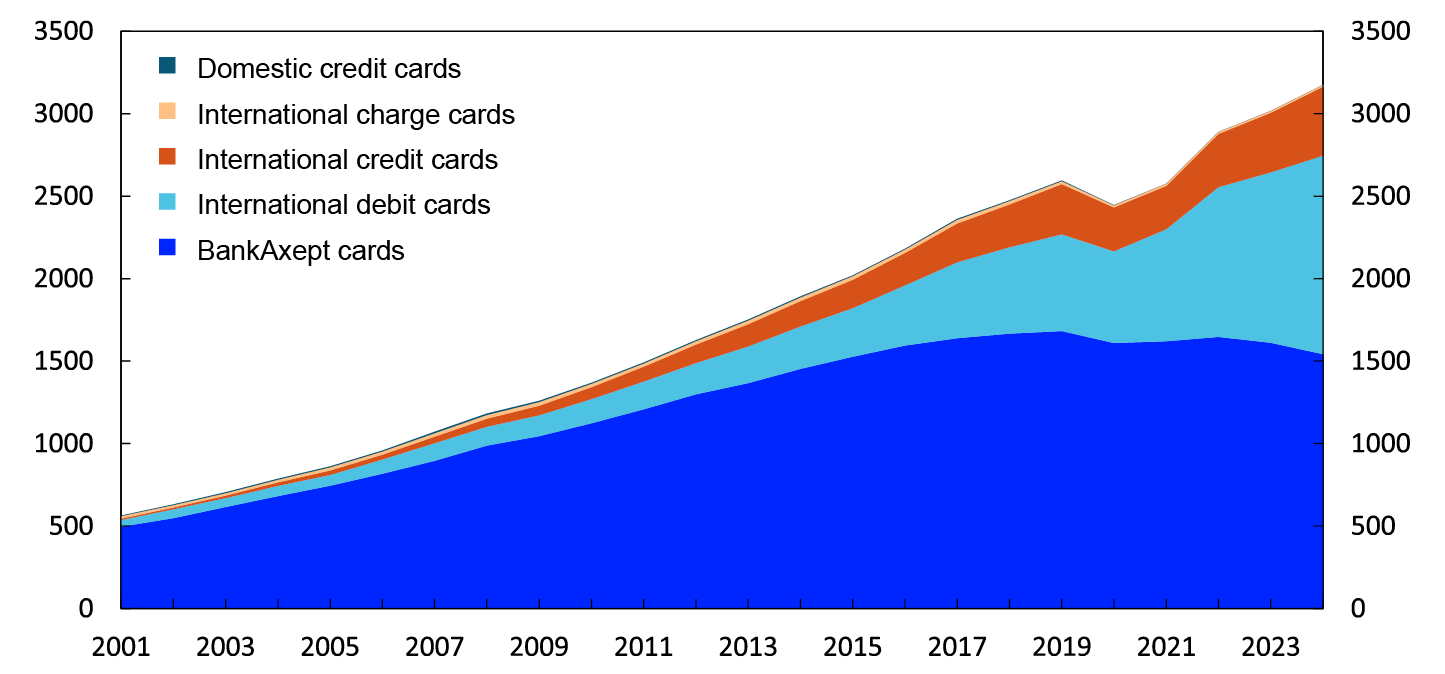

Electronic retail payment services include payments using bank deposits via payment instruments such as payment cards and account-to-account (A2A) transfers.

Finanstilsynet (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway) is responsible for supervising and overseeing retail payment services systems and regularly publishes reports on the condition of these systems. Norges Bank monitors developments in the use of different means of payment and payment instruments in retail payment services and publishes an annual report on this segment. Retail Payment Services 2024 provides details on developments up to and including 2024.

A key development is strong growth in the number of mobile payments. While such payments have been available in Norway for over a decade, it is only now, in 2025, that usage appears to be increasing significantly. This topic is discussed further in “Mobile payments in shops are on the rise”.

Banknotes and coins

Norges Bank is responsible for meeting public demand for cash in both normal times and times of crisis by supplying banks with cash.

In 2024, the amount of cash in circulation averaged just over NOK 38.5 billion, which is slightly lower than in previous years, reflecting less seasonal variation than before. Cash as a share of narrow money (M1) is 1.4%, placing Norway among the countries with the lowest percentage of cash. However, the amount of cash in circulation does not indicate how often this cash is used for payments. To shed light on this, Norges Bank conducts an annual survey of a sample of Norwegian households. The 2025 survey shows that the public uses cash for 2% of their payments. See Retail Payment Services 2024 for more detailed information about cash usage.

Although cash usage in Norway is extremely low in a global context, cash still serves important functions in the payment system. Currently, there are no alternative means of payment or payment instruments that fulfil all the functions that cash has related to contingency preparedness, financial inclusion and privacy. This topic is discussed in more detail in “Cash still plays an important role in the payment system”.

2. A secure payment system

The financial infrastructure is robust and meets strict security, testing and continuity requirements. Nevertheless, there will always be vulnerabilities, and over time the threat landscape has become more aggressive. Contingency arrangements must therefore be further strengthened.

This section highlights some of the key priorities in Norges Bank’s security and contingency preparedness work in the financial infrastructure

Strengthening contingency arrangements

The security and contingency arrangements of individual entities are the payment system’s first line of defence. Both the authorities and private financial infrastructure operators have a high awareness of risk, vulnerabilities and the necessity of systematic contingency planning. There are strict security and testing requirements, and backup solutions are required. Exercises are conducted regularly, and participants are quick to share information with each other about incidents and threats. Such efficient collaboration promotes good incident management and increases financial infrastructure resilience. Incidents and attacks have rarely developed into severe negative consequences.

At the same time, more serious scenarios that make even well-protected systems unavailable must be taken into account. Europe is now facing the gravest security policy situation since the Second World War, with armed conflict in Ukraine and escalating rivalry between the major global powers. National threat assessments from the Norwegian National Security Authority (NSM), the Norwegian Policy Security Service (PST) and the Norwegian Intelligence Service (NIS) highlight the increased likelihood of sabotage of critical infrastructure and sophisticated cyberattacks from both organised criminals and hostile nation states with significant resources. Climate change increases the probability of natural disasters that can destroy critical infrastructure. Contingency arrangements must therefore be strengthened to deal with more serious scenarios.

Vulnerabilities in the financial infrastructure

Complexity and interdependencies

The financial infrastructure comprises many components that are both interdependent and dependent on underlying infrastructure such as electricity supply and electronic communication. If critical components fail, this can have a rapid major impact on the system as a whole. As a result of the complexity in the number of systems and interdependencies, with associated complex supply chains, the number of potential attack surfaces also increases.

Critical components in financial infrastructure, electronic communication and electricity supply are generally well protected, and backup solutions are in place. But in crisis situations such as war, sabotage or natural disasters, one or more components may nevertheless become unavailable over an extended period. The risk associated with such extreme incidents has risen and the system must be strengthened to mitigate them.

Attractive targets for attack

As holders and managers of substantial assets, banks, key market participants and financial market infrastructures (FMIs) in the Norwegian financial system are attractive targets for various threat actors.

Digital profit-motivated crime is on the rise, and organised crime constitutes a substantial threat to financial institutions and their customers. Armed robbery is currently less common than before, but robbery still occurs. However, instead of banknotes and coins, criminals steal card information, identities and access, as well as sensitive and valuable data. A more tense security policy landscape also means that complex threats, where state and criminal actors collaborate, occur more frequently. Technological advances, such as artificial intelligence, are providing attackers with new tools.

Outsourcing and concentration risk

In recent years, the financial sector’s use of outsourced services has increased. In parallel, the advantages of economies of scale in the operation of IT systems and external expertise have led to the consolidation of IT and data centre service providers in the financial sector.

Outsourcing can lead to better, more cost-efficient and more resilient financial market infrastructures (FMIs). At the same time, a higher degree of outsourcing and concentration constitutes a vulnerability. Many entities use the same software, hardware and system platforms. Among other things, cloud services are becoming more widespread, and the market is dominated by a few multinationals. Dependence on only a few key providers is also the case for a number of critical functions in the Norwegian financial infrastructure. In pace with the rise in market concentration in the provider market, providers’ corporate structures have become more complex and often consist of a number of subcontractors that may be subject to regulation in different jurisdictions. This makes it difficult for authorities and system operators to maintain an overview of providers’ risk exposure in technological security, personnel security and regulatory changes in providers’ home countries.

The Government has, in the White paper on total preparedness1 presented on 10 January 2025 and deliberated by the Storting (Norwegian parliament) on 6 May 2025 and in the National Security Strategy that was presented on 8 May 20252, clearly signalled the need to strengthen contingency arrangements across all sectors. Norway’s work to strengthen total preparedness, including preparedness in the payment system, is well underway. A working group appointed by the Ministry of Finance has recently published a report including recommended measures to strengthen contingency arrangements in the digital payment system. A number of these measures have also been recommended by the Payment Commission appointed by the Norwegian government. The recommendations are discussed in “Contingency arrangements in severe crises”.

Cash is still an important part of the total preparedness of the payment system and is the only alternative should electronic payment solutions fail completely. This is also reflected in “A practical guide to payment preparedness”. However, for cash to fulfil its function in a contingency, it must be available and easy to use in a normal situation as well. This topic is discussed in further detail in,“Cash still plays an important role in the payment system”.

The Lysne III Committee on national control

The Committee defines the government’s national control as:

- Control capability of making effective decisions through, for example, regulation, ownership and agreements

- Freedom of action to carry out decisions as independently as possible from foreign actors and influence.

The Lysne III Committee has focused on making specific proposals on how the government can ensure national control of critical digital communications infrastructure. As stated in the government’s white paper on total preparedness, the Committee’s work has transfer value to other sectors that manage critical infrastructure:

“The Committee will provide the Government with a basis for assessing how we can safeguard and strengthen national control of critical infrastructure, for example through ownership. This also has transfer value to other sectors that manage critical infrastructure, critical value chains and security of supply. It is important for the Government to have a good knowledge base in order to ensure adequate national control of critical infrastructure across different sectors.”

According to the Committee’s analyses, the approach to national control of critical digital infrastructure has so far been on an individual and case-by-case basis. One of the Committee’s recommendations is to establish and maintain an overall strategic vision for Norway’s national control of critical digital infrastructure and an analysis of the gap between the current situation and the strategic vision. This will make the Government’s approach to national control more systematic and planned. The recommendation can also apply to the financial sector.

Safeguarding national control of critical functions

Key financial infrastructure functions and services, such as cross-border payments and FX trades are essentially international. International cooperation and contributions from experts in other countries can strengthen both the operation of and developments in the Norwegian financial infrastructure. In certain crisis scenarios, available operational or contingency arrangements in other countries can help maintain critical functions in Norway.

At the same time, foreign ownership, outsourcing services abroad and dependence on key resources from other countries are elements that can weaken national control, particularly in a crisis or conflict situation. This issue has recently been considered by the Electronic Communications Security Committee (Lysne III Committee) (see “The Lysne III Committee on national control”). The Committee submitted its report to the Ministry of Digitalisation and Public Governance on 28 February 2025.3

Norges Bank will promote a secure payment system and contribute to contingency arrangements. The assessment of whether the authorities have sufficient national control of critical payment system functions is a key part of this. In line with recommendations from the Lysne III Committee, the development and continuous updating of an analysis of national control of critical payment system functions will provide a more comprehensive basis for assessing the need for measures. Norges Bank will contribute to systematic and planned assessments of national control, and maintain dialogue with the Ministry of Finance, Finanstilsynet (the Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway) and the financial sector on this topic in line with strategic priorities in the National Security Strategy.

Operations, security and preparedness in the FMIs are the responsibility of the system owner, regardless of whether or not the service has been outsourced. When multiple tiers of subcontractors have been used, the responsibility extends to the entire provider chain. To fulfil this responsibility, system owners must have sufficient expertise and capacity to manage and control deliveries from their providers. When providers are located abroad, greater effort is needed to gain sufficient insight into their operations and risk exposure in technological security, personnel security and regulatory changes in providers’ home countries. System owners should also have realistic exit strategies for changing providers without disrupting services in instances where operating conditions change in the provider’s home country. These topics will be prioritised in Norges Bank’s dialogue with entities that are subject to the Bank’s oversight and supervision.

Collaboration, exercises and raising awareness

Awareness of a more aggressive threat landscape is generally high in the financial sector, and close cooperation between the authorities and the domestic and international financial sector is an important contribution to incident management and preparedness. The same can be said for regular exercises.

In its white paper on total preparedness, the government announces that it will establish a new council structure for the ministries’ work related to preparedness planning and status assessments in civilian sectors. The aim of the new structure is to improve the ability to maintain the continuity of critical functions, uncover cross-sectoral dependencies and prevent and handle incidents, among other things.

Financial services are defined as one of seven critical functions. For each critical area of society, the responsible ministry must ensure that there are capable preparedness councils in place consisting of relevant participating agencies, private businesses and organisations.

For financial infrastructure, a body has already been established with a mandate that covers most of the objectives in the Government’s new council structure: The Financial Infrastructure Crisis Preparedness Committee (BFI)4. The BFI was established by Norges Bank’s Executive Board in 2000. Since 2010, the BFI has been chaired by Finanstilsynet, which has also served as the secretariat and calls Committee meetings. The Ministry of Finance, Norges Bank and a number of key FMIs participate in the Committee.

Exercises conducted through bodies such as the BFI and others help to increase participants’ understanding of their own and others’ procedures and roles, while also strengthening collaboration. Regular and open dialogue about individual experiences and current challenges helps foster knowledge-sharing among all participants in the financial infrastructure. Highly publicised incidents such as NotPetya, SolarWinds and CrowdStrike highlight the potential for the rapid spread of both operational errors and targeted attacks. Such incidents emphasise that defending against adverse incidents requires strong collaboration and swift information sharing across organisations, sectors and countries.

Exercises also contribute to hardening systems. Vulnerabilities and deficiencies in systems and processes are often detected during testing, providing an opportunity to address these issues before they can be exploited or cause significant disruptions. By challenging systems through exercises, it is possible to prevent prolonged periods of stable operations with few serious incidents leading to reduced vigilance, de-prioritisation of security measures and limited practical experience in activating and using contingency solutions.

Exercises also help to foster a strong security culture. Insider threats, such as rogue employees or mistakes made by employees are particularly difficult to detect and cannot be fully addressed through technological defences. Personnel security and a robust security culture at all levels are essential for preventing, detecting and managing such threats. Norges Bank will follow up on this topic in particular in dialogue with financial sector participants in connection with oversight, supervision and testing in the period ahead.

Advanced threat-led penetration testing

The European TIBER framework provides guidelines for testing financial institutions’ ability to detect, defend against and manage advanced cyberattacks5. Finanstilsynet and Norges Bank are together responsible for the Norwegian implementation of this framework, which was established in October 2021. Active testing began in 2022. Norges Bank has established a dedicated TIBER Cyber Team to assist organisations that wish to perform tests under the TIBER framework with planning, coordinating involved entities, conducting risk assessments, executing and evaluating the tests.

Security tests under the TIBER framework are demanding and expose critical functions, systems and processes within each organisation to realistic attack scenarios carried out by red team attackers. These attacks are based on plausible threat scenarios developed based on assessments conducted by the Norwegian intelligence service, the Norwegian Police Security Service (PST), the Norwegian National Security Authority (NSM) and Nordic Financial CERT (NFCERT). The organisations that are tested own the test results. This is important as the tests may reveal sensitive information related to business operations.

At the same time, sharing insights from these tests enables the payment system as a whole to strengthen its defences. To facilitate this, Norges Bank established the TIBER-NO Forum, where participants can confidentially exchange information and experiences related to TIBER testing in a secure environment for discussing relevant and sensitive issues. The execution of these tests and the sharing of knowledge and experiences both during and after testing significantly strengthens the resilience of individual systems and the financial infrastructure as a whole.

In 2024, Norges Bank completed a TIBER test on its own settlement system, NBO. No critical vulnerabilities were identified, and the system is well-equipped to handle advanced cyberattacks. Nevertheless, areas of improvement were discovered, and Norges Bank has implemented measures to further enhance its systems and processes. This forms part of Norges Bank’s ongoing work on cyber security and risk management, aiming to uphold the highest standards of security and protection.

Testing under the TIBER-NO framework has so far been voluntary. However, with the introduction of the new Act on digital operational resilience in the financial sector (the EUs Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA) transposed into Norwegian law), threat-led penetration testing (TLPT) will become mandatory for the most significant entities.

Experiences from TIBER testing

To date, seven TIBER tests have been completed, with more underway. Three of the completed tests were cross-border tests of bank branches in Norway. Through testing, Norges Bank has benefitted from general insights into the security of the financial infrastructure. By sharing these insights, others can benefit and address potential vulnerabilities within their own operations before they can be exploited by threat actors.

All organisations routinely perform penetration testing, but none have previously conducted threat-based penetration testing at the level of the TIBER framework. TIBER is a far more comprehensive and demanding method, but it is also significantly more valuable for strengthening cybersecurity. The overall security level is high, especially in systems exposed to the internet. However, security inside outer defences is not always as robust, and many are vulnerable to individuals inside the organisation escalating their access beyond authorised levels.

Another key insight is that organisations invest heavily in security technology, but this investment is not always well adapted to their specific IT environment. This weakens their ability to detect warning signals of cyberattacks. Furthermore, testing revealed concentration risk related to the widespread use of the same security service providers and similar security software. This may lead to difficulties if a service provider’s customers are impacted by an attack at the same time.

The tests also show that human weaknesses can still be exploited through attack methods such as phishing emails. When combined with weak internal work processes, this provides attackers with opportunities.

In addition, there is a clear trend that resilience is inversely proportional to the number of systems an organisation operates. With a large number of systems, the attack surface is large, but security resources are often not scaled proportionally to the size of the attack surface.

Awareness of long-term trends

Not all threats are directly aimed at the financial infrastructure, nor are all vulnerabilities immediate. Some challenges evolve slowly, and trends can also create opportunities (see box).

Long-term challenges and opportunities must be addressed on multiple fronts, not least through effective collaboration and open dialogue between authorities and private entities.

Innovation is beneficial to the payment system, but it must be responsible. In most cases, private stakeholders are best placed to drive innovation and develop new, user-friendly solutions. However, unregulated markets and entities do not always sufficiently take into account societal considerations. Effective collaboration between authorities and private entities is crucial in maintaining an efficient and secure payment system over time.

An example of such collaboration is Norges Bank’s initiative to establish the Norwegian Payment Forum6 in 2024, involving participants from other authorities, the financial sector and other key stakeholders. The Payment Forum is an arena to exchange information and discuss measures and strategies that contribute to the long-term development of the payment system in Norway and internationally. The Forum held its first meeting in June 2024. Matters discussed so far have included Norges Bank’s work on the next generation settlement system, research into a Norwegian central bank digital currency (CBDC), the EU’s work on a digital euro and the implications for Norway, as well as digital identity and financial inclusion.

For many years, Norges Bank has been researching whether a CBDC should be introduced in Norway. A key question has been how to have a precautionary approach to developments that could entail opportunities for or threats to an efficient and secure payment system in NOK. The research is exploring whether a CBDC is a suitable instrument in new payment arenas for ensuring access to a means of settlement in which everyone can have confidence, while fostering responsible innovation and improving payment contingency arrangements. A measure in the project has been the establishment of a technological sandbox where Norges Bank and banks can together test different solutions in practice. This topic is discussed in more detail in “Tokenisation and central bank money”.

One such new payment arena is the increasing prevalence of cryptoassets and stablecoins. An increasing number of interconnections between cryptoassets and traditional finance increases systemic risk associated with cryptoassets. The way in which these assets are regulated will significantly impact the risk they will represent over time. This topic is discussed further in “Stronger interconnections between cryptoassets and traditional finance”.

Long-term challenges

Technological advances: Technological advances occur rapidly, while developments in structures, the design and the regulation of the established financial infrastructure takes time. Although NOK is legal tender in Norway, it is not prohibited to agree on other means of settlement for a transaction. Alternative payment systems and means of payment that are attractive in terms of ease of use and that gain sufficient public trust can quickly become widespread. Multinationals could assume a dominant role in the payment system – even in Norway. This could make safeguarding national societal interests challenging and set the terms for how Norway’s payment system functions.

National centres of expertise: In pace with the outsourcing of an increasing number of support and core services, the operation and development of these services are increasingly based abroad. Even for systems and services located in Norway, critical tasks are often performed by specialists from other countries. This is not unusual in a small open economy, and in most cases, expertise from strong centres of expertise from abroad adds significant value to the Norwegian financial infrastructure. However, if national centres of expertise become too small over time and if distance to the operation and development of critical systems increases, the ability to manage and control service delivery may be weakened.

Confidence in the public sphere: Norway is one of the world’s most digitalised societies, with widespread, high confidence in central IT systems and the entities responsible for them. However, confidence can disappear quickly. Operational incidents that lead to service disruptions or leaks of sensitive information can undermine confidence in systems and institutions. For trust-dependent institutions – such as banks – the potential spread of misinformation on social media presents a potent and potentially destructive weapon of attack. Disinformation or misinformation generally erodes trust in public information. Similarly, card fraud, scams, identity theft, extortion and fear of illegal surveillance can diminish confidence. A loss of confidence may lead more people opting out of using efficient digital solutions.

In focus

Next generation settlement system

It has become necessary to explore the future design of Norway’s settlement system due to technological advances and changes in the settlement systems of Norway’s neighbouring countries. Norges Bank therefore launched a study of the next generation settlement system as part of the Bank’s strategic goals for the period between 2023 and 2025. The overall assessment is that collaboration with Nordic and other European central banks is the best choice to ensure the secure and stable operation of the settlement system in the long term.

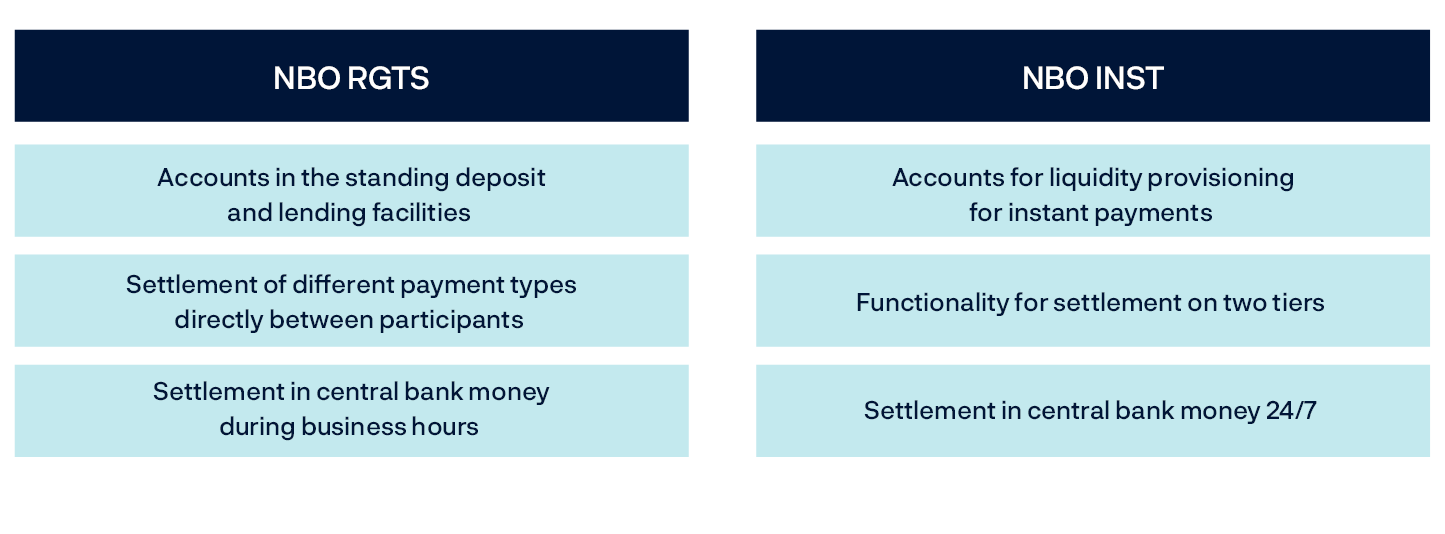

The next generation of Norges Bank’s settlement system (NBO) will comprise two separate services, NBO RTGS and NBO INST (see Chart A.1).

Chart A.1: Next generation settlement system

NBO RTGS

NBO RTGS will become Norges Bank’s standing facilities and interbank settlement service. Banks’ accounts with central bank money in NBO and accrued interest on deposits and loans are key monetary policy and liquidity management instruments for Norges Bank. All electronic payments in NOK are ultimately settled between banks in NBO RTGS.1 This is the case for normal payments for households and firms, large payments in financial and FX markets and payments involving the public sector.

For NBO RTGS, Norges Bank has launched a project to make the settlement system more component-based, which means dividing a system into smaller units that can be developed, maintained and updated independently. This provides a number of advantages, including greater flexibility, simpler maintenance and the ability to adjust more swiftly to new needs or technological advances. The measures include isolating functions that are unique to Norges Bank, such as those used to implement monetary policy and liquidity management and the establishment of a national contingency solution for NBO. In addition to strengthening contingency arrangements, the measures will also simplify the transition to a new settlement system in the future.

Predictability is important for providing appropriate framework conditions for further financial-sector development of payment and settlement services. Norges Bank has assessed two alternatives for the future NBO RTGS: acquiring a new dedicated platform for NBO, as is in place today, or connecting to a common platform through the Eurosystem’s T2, as the other Nordic countries are now doing. As neighbouring central banks have decided to migrate to T2, Norges Bank will no longer have the option of working with them in following up service providers and further developing a dedicated platform.

The Bank’s current assessment is that collaboration with other central banks is the best long-term choice. This would make the Bank better equipped to ensure stable operations, protect the settlement system against attacks and further develop new features and services.

Norges Bank has initiated formal discussions with the European Central Bank (ECB) and thus commenced a process with a mutual exchange of information for necessary clarifications. Among other things, more information is needed for addressing certain remaining questions related to security and contingency arrangements. Designing an appropriate model for smaller banks’ participation in T2 is also necessary.

For Norges Bank, T2 participation would mean that Norges Bank retains control of NOK settlement, as well as liquidity management and monetary policy. Ensuring national control also means that the authorities have sufficient control capability and freedom of action to maintain critical functions in the event of crises or conflicts. T2 contingency arrangements are comprehensive and will, together with the establishment of a national contingency solution, provide a resilient settlement system. Norges Bank will engage in dialogue with the Ministry of Finance and the Norwegian National Security Authority on this matter.

Norges Bank works closely with Riksbanken and Nationalbanken to ensure a common approach to the development of the settlement system. This collaboration provides opportunities for knowledge-sharing and the harmonisation of payment solutions across countries.

The next generation settlement system and T2 participation have been circulated for public comment. The financial industry and other stakeholders were asked for input about participation in the Eurosystem’s common T2 platform. The Bank was particularly interested in feedback on functionality and the implementation project, as well as on opportunities and innovation that participation in T2 may provide. The submission deadline for consultation responses was 16 May 2025. Norges Bank has received eight consultation responses, and these are published on the Bank’s website (in Norwegian only). Submissions will be considered in the Bank’s further work and in the involvement of the financial industry and other market participants.

A final decision will be made once the necessary clarifications have been addressed. Norges Bank aims for the decision basis to be ready in the course 2026.

NBO INST

NBO INST will become Norges Bank’s instant payment settlement service with around the clock availability. Instant payments ensure that payees receive money directly into their accounts seconds after payments are made – 24/7/365.

Norges Bank has decided to establish NBO INST as a new service for instant payments in NOK and signed an agreement with the European Central Bank (ECB) to participate in TARGET Instant Payment Settlement (TIPS) on 28 November 20242. Participation in TIPS3 means real-time gross interbank settlement, ie each transfer is settled individually in central bank money on the Eurosystem’s platform.

The implementation project for NBO INST has now been established. The project includes the establishment of instant payments in NOK and the migration of existing participants from NICS Real, the current instant payment solution. The instant payment service is scheduled to become operational in the first half of 2028.

In cooperation with the financial industry, Norges Bank will plan for the transition to the new settlement service to be implemented at the lowest possible risk for all parties involved. It is appropriate to assess other services, such as cross-currency instant payments, participation for new types of market participants and the development of new instant payment services for firms and the public sector.

The NBO INST service for instant payments will be competitively neutral, secure and efficient and facilitate faster and more efficient money transfers to and from users in other Nordic and European countries.

An important focus area for the Eurosystem is cross-border and cross-currency payments (see box below). This supports the G20’s targets for enhancing the efficiency and security of global payment systems. Like the central banks of Sweden and Denmark, Norges Bank is considering implementing such payment solutions in NOK. Cross-currency instant payments will promote a more integrated payment infrastructure between Norway, the Nordic countries and the rest of Europe, while also potentially strengthening competition and payments innovation.

The EU Instant Payment Regulation (IPR) is expected to be transposed into Norwegian law. Upon transposition, the regulation will require that both settlement and payment systems allow for new types of market participants, such as payment and e-money institutions. This may foster innovation and the development of new services that can meet future market needs.

Cross-border payments in the Eurosystem

In October 2024, the ECB launched initiatives to improve cross-border and cross-currency payments1. These initiatives can be classified into two work streams:

Implementing cross-currency settlement services in TIPS: This will allow payments originating in one currency to be settled in another currency - in central bank money. Initially, three currencies: the euro, the Swedish krona and the Danish krone will join the initiative, which could expand to include other currencies onboarded to TIPS in the future.

Exploring possible links between TIPS and other real-time settlement systems: Among other things, this includes joining the multilateral network of instant payment systems, Project Nexus, led by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), and establishing a bilateral link with India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI).

The ECB emphasises advantages such as reduced costs, increased speed and transparency of cross-border payments, including remittances. More attractive cross-border payments in participant country currencies also strengthen monetary sovereignty as interlinking prevents currency substitution and the domination of the market by a few global payment institutions.

At the same time, difficult challenges must be overcome, including harmonising standards and regulating in multiple jurisdictions. Proper governance and oversight structures, including ensuring compliance with anti-money laundering requirements and countering the financing of terrorism, must also be established. Analysis and evaluation of the benefits and challenges are a part of the exploratory work being conducted by the Eurosystem.

1 See ECB (2025a).

TARGET Services

The European Central Bank (ECB) defines the Eurosystem as a collaboration between EU member countries that use the euro. The Eurosystem has established and operates TARGET Services.

TARGET Services include the following :

- T2, which consists of a real-time gross settlement (RTGS) component and a central liquidity management system (CLM) component

- TIPS, the system for real-time gross settlement

- T2S, the securities settlement platform

The central banks of EEA countries that are non-EU members are allowed to participate in TARGET.

There are currently 20 central banks that use the Eurosystem’s (T2) settlement system in EUR, and since April 2025, these also include Danmarks Nationalbank for settlement in Danish krone.

TIPS is a market infrastructure service launched by the Eurosystem in November 2018. It enables payment service providers to offer fund transfers to their customers in real time and around the clock, every day of the year. TIPS settles instant payments in central bank money and processes payments in EUR, SEK, and, as of April 2025, also in DKK.

At the top of TARGET’s governance structure is the Governing Council, in which only euro area countries participate. The Market Infrastructure Board (MIB) is responsible for the operation and development of Target Services. Central banks participating with their own currencies hold two MIB seats. Like the central banks in Sweden (the Riksbank) and Denmark (the Nationalbank), Norges Bank will participate in the Non-Euro Currency Steering Group, which puts forth matters to the MIB.

Contingency arrangements in severe crises

The threat landscape has worsened over time, and the eventuality that even well-protected systems and continuity solutions could become unavailable must be taken into account. Contingency arrangements must be strengthened to deal with more serious situations.

In order to pay for goods and services, the payment system must function. Economic activity will come to a halt if payments cannot be made. As payments are now primarily made electronically, a disruption to parts of the electronic payment system will quickly have major ramifications.

The Norwegian payment system is secure, efficient and stable, with few disruptions. Continuity and contingency arrangements are in place for critical functions and systems, and these arrangements are subject to regular testing. A worsening threat landscape means that Norway must be prepared for more extreme scenarios where even well-protected services critical to society become unavailable. Internationally, there have been examples of serious incidents in most parts of the payment system, from cash register and card terminal systems at points of sale (POS) to banks’ customer systems and key clearing and settlement systems. Norway must be prepared that such incidents could also impact Norway.

In recent years, the authorities have launched several initiatives to explore whether and, if so, how contingency arrangements in the payment system should be strengthened:

- In 2023, the Government appointed a commission to explore how society can ensure secure and simple payments for all, including an assessment of the need to strengthen contingency arrangements. The Payment Commission submitted its report in November 20241.

- In 2023, the Ministry of Finance issued a mandate to a working group comprising representatives from the banking industry and the authorities to consider the need to strengthen contingency arrangements in the digital payment system. The working group submitted its assessments in February 20252.

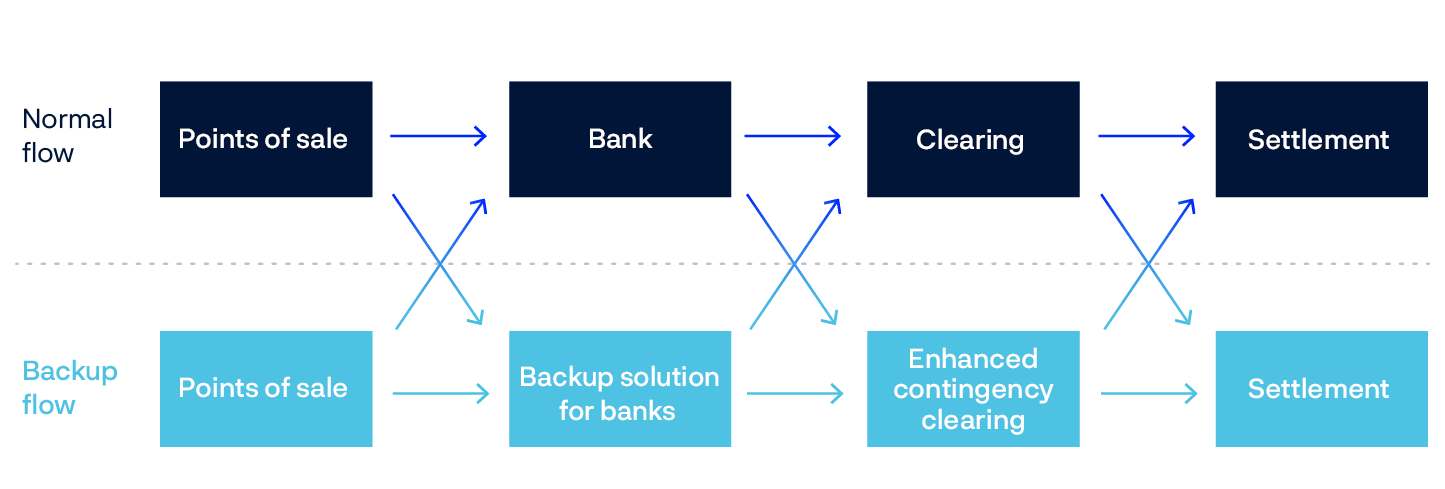

The Payment Commission and the working group have recommended several measures to strengthen the ability of the payment system to function also in a serious crisis. The proposed measures aim to strengthen contingency preparedness throughout the payment value chain: at points of sale, at banks, in clearing and settlement systems and in households. If the recommended measures are implemented, alternatives would be established for the most common form of payments for almost the entire payment value chain (Chart B.1).

Chart B.1: Backup solutions for all links in the payment chain

Source: Norges Bank

Points of sale would then have alternative solutions to send payments and be able to use different communication infrastructures. There would be a backup solution for basic banking services, as well as backup solutions for clearing and settlement. Norges Bank supports the recommendations of the working group.

Some of the key measures recommended by the Payment Commission and the working group are described below.

Enhanced contingency arrangements at points of sale

Firms, in particular those that sell basic necessities, should consider having contingency arrangements in place in the event of card terminal or cash register failure or disruption to their regular communication infrastructure. There are a number of ways in which points of sale can prepare for such incidents, and some retailers already have alternative solutions in place to deal with incidents where ordinary payment solutions become unavailable. One such arrangement is having alternative cash register systems, another is having contingency terminals from an alternative provider and a third is having agreements in place for the use of alternative methods to communicate with the underlying payment infrastructure (terminals with mobile broadband access, satellite communication options etc). The firms themselves have an interest in maintaining operations. Sound contingency preparedness among firms will be in addition to the contingency arrangements already integrated in the payment system.

Expanded continuity and contingency solutions for card payments

Maintaining the public’s opportunity to pay by card is key to ensuring that they have access to basic necessities. Currently, backup solutions for BankAxept cards ensure that the public can pay for basic necessities for a full week in the event of communication disruptions between points of sale and the underlying payment infrastructure. So far, the solution has proven sufficient to handle almost all incidents. Since the solution was introduced in 2021, the balance of risks has shifted, and it must be assumed that extreme weather events that impact communication locally and regionally will occur. Both the working group and the Payment Commission have proposed a further expansion of BankAxept’s backup solution for basic necessities and to take into account situations where systems or communication will be down for more than a week.

Independent contingency arrangements for the banking system

Banks hold the public’s savings and current funds and make them available for use. Banks perform a critical role in society and are subject to strict requirements relating to security and contingency and the testing of continuity and disaster preparedness solutions. Banks work to reduce their risk and ensure that their services remain available. Major operational service disruptions are few and far between among Norwegian banks.

However, cyberattacks are becoming increasingly sophisticated and attacks on firms’ backup copies are also increasing. There have been examples internationally where banking data has been encrypted, which can also happen to Norwegian institutions.

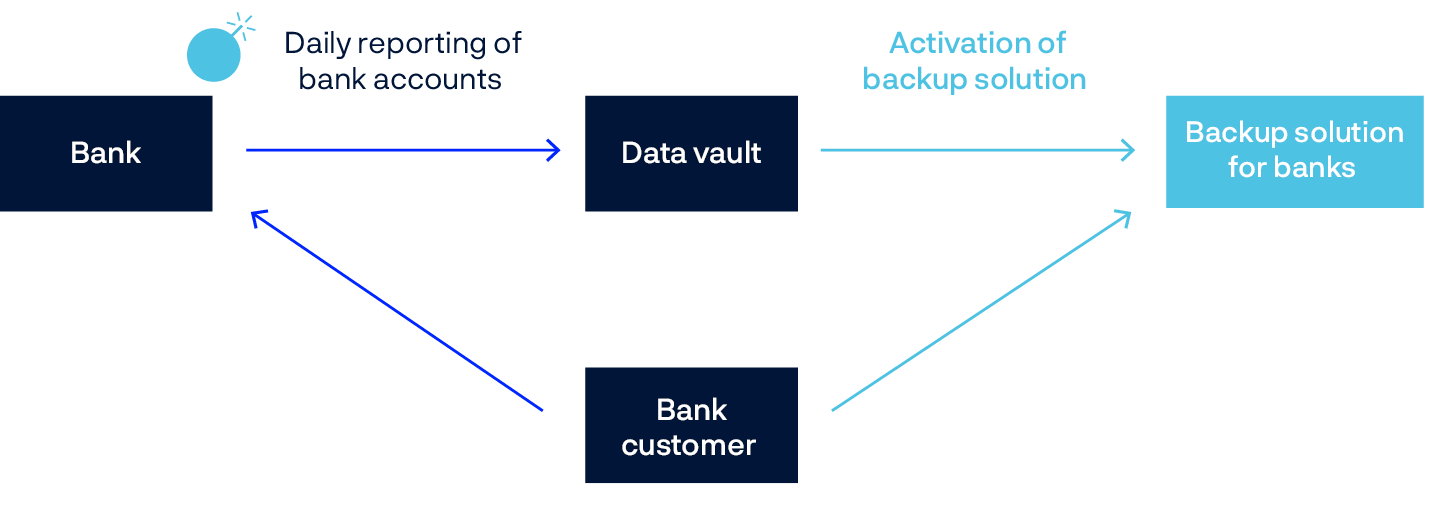

Some countries have implemented measures to handle outages in banks’ core systems (see box below). Two contingency arrangements are particularly relevant in such situations (Chart B.2): One is establishing an independent data vault into which banks report information on customers’ deposits and loans. The data vault should be completely separate from banks’ regular systems to prevent the same incident from also making these data unavailable and could be a shared resource for the banking sector. The other measure is establishing independent solutions that can continue the operation of account and payment solutions for banks that experience severe operational disruptions (for example as a result of a cyberattack).

Chart B.2: A backup solution for banks

Source: Norges Bank

Contingency arrangements for banks and payments in various countries

In 2022, Finland implemented a new Act for arrangements to ensure supply chain security in the financial sector. The Act describes two separate systems for enhanced contingency arrangements for payments: one independent solution for contingency interbank clearing and settlement, and one solution which includes daily account reporting solutions and independent contingency arrangements for basic banking services, including giro and card payments. The solutions have been operational since the implementation of the Act.

In Denmark, a system for offline card payments for basic necessities was recently implemented, supported both in the national Dankort card system and in some international card systems. In Sweden, offline card payments are possible to some extent, and the industry is working with the authorities to implement more extensive support for offline card payments for basic necessities.

In the Baltics, offline Visa card payments have been possible in Estonia since 2024, while a similar solution was introduced in Latvia through a new Act which took effect on 1 January 2025.

Iceland, like Sweden, Finland and the Baltics, has no national card system like BankAxept in Norway. In order to ensure that digital payments can be made if card systems are unavailable, efforts are underway to establish a Request to Pay (RTP) solution for use at points of sale. This will be an account-to-account payment solution and thus not use card networks.

Ukraine has established a concept called Power Banking. This currently consists of around 2400 geographically distributed branches of many different banks that are equipped with backup power sources and communication channels. These branches provide basic banking services to customers, irrespective of which bank they use

In 2015, a number of financial institutions, service providers and national trade associations in the US founded the organisation Sheltered Harbor. Sheltered Harbor provides standards and processes for how financial institutions can create independent contingency arrangements for their core services, in particular for maintaining account access and payments in a scenario where the firm’s regular systems and continuity solutions become unavailable. Sheltered Harbor also certifies the solutions introduced by the firms. Unlike Finland, where solutions are owned by the authorities and participation is mandatory, Sheltered Harbor does not provide any set solutions, certification is voluntary and the authorities do not require firms to join up.

Enhanced preparedness for interbank systems

Clearing and settlement are two of the key subsystems in the payment system. As a result of a disruption or failure in these systems, payment services could come to a halt and could rapidly lead to major consequences for society.

Today, contingency arrangements have been established for these systems, but they may also become unavailable in some situations. To further ensure that payments can be cleared and settled even in more extreme situations, additional contingency arrangements should be established.

Norges Bank has begun work to establish such an independent contingency arrangement for Norges Bank’s settlement system. It is important that independent solutions are also in place for payment clearing.

Preparedness among households

Sound contingency arrangements among banks and other payment system participants are the first line of defence in dealing with disruptions and serious incidents affecting electronic payment services. But households can also play a part in limiting the consequences of electronic payment infrastructure failure.

Households should have multiple payment methods, including multiple types of payment cards, some available cash and accounts in several banks. Households that use mobile phones for payments should in addition have a BankAxept card. In some instances, current contingency arrangements for card payments require authorisation using a physical card.

Norges Bank has updated its advice on payment preparedness, which now specifically recommends having a BankAxept card available, see Norges Bank’s web page on payment preparedness. Similar advice can also be found at Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection (DSB) Safe everyday life.

The availability of cash in the event of failure in electronic solutions

Norwegian banks’ obligation to ensure satisfactory cash services also applies in the event of failure in electronic payment solutions. In-store cash services (KiB) have become a significant part of banks’ cash services, but KiB does not function when BankAxept’s back-up solution kicks in. This means that a large part of the ordinary cash supply will be disrupted in situations where the backup solution is in use.

The deposit and withdrawal of cash in the KiB solution should therefore be facilitated in a very severe crisis, also when the expanded BankAxept backup solution is in use. This will increase availability and make cash circulation more efficient in a contingency.

Alternative ID solutions

Both for reasons of preparedness and to ensure that everyone has access to basic banking services, it is important that there are alternatives to BankID for identification needed for online banking login and in connection with payment authentication.

Cash still plays an important role in the payment system

Even though cash usage is low, cash has key functions in the payment system. Cash is crucial for contingency considerations and for financial inclusion, but for it to fulfil its functions, it must be sufficiently available and easy to use.

Developments over time have shown that this is not ensured by the market alone, and that regulation is therefore necessary. Norwegian banks are under statutory obligation to provide satisfactory cash services to their customers in both normal and contingency situations. Furthermore, consumers’ right to pay cash has been strengthened.

Cash has important characteristics

At present, there are no alternative means of payment or instruments that can match all the functions of cash related to, among other things, contingency arrangements, financial inclusion and privacy.

Cash is physical and both a means of payment and a payment instrument in one.1 Cash can be stored and used independent of third parties or electronic systems, and settlement is immediate and final upon receipt. This means that cash can also be used for payments in situations where the electronic payment system fully or partly fails. Cash is also important in terms of financial inclusion as it does not require digital literacy, bank account access or electronic instruments.

In addition, cash provides the general public with access to central bank money. Among other things, this means that cash is without credit risk, and the ability to exchange deposit money into cash at parity has traditionally been viewed as supporting confidence in deposit money. As an alternative to deposit money and electronic payment solutions, cash provides additional options in the payments market and may have a disciplinary effect on providers of electronic payment solutions.

Cash is also unique in that it has legal tender status (cf Section 3-5(1) of the Central Bank Act). This means that, unless another means of payment is agreed upon in advance, creditors and debtors have a mutual obligation to accept banknotes and coins as settlement for a claim. Section 2-1 (3) of the Financial Contracts Act provides special provisions on consumers’ right to pay cash (for more details, see the section on the right to pay with cash).

Furthermore, the physical characteristics of cash provide a higher degree of privacy as it leaves no digital trace. Making cash payments also allows some users to better handle their personal finances.

Since cash is physical, it is primarily suited for payments at physical points of sale or in other settings where payers and payees meet in person and the amounts are moderate. These types of payments can be significant for participation in everyday life and are considered an important part of being able to make payments in contingency situations. Norges Bank and the Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection (DSB) therefore recommend that the population keep some cash, preferably in small denominations, as part of their contingency arrangements for payments.2

Cash usage in Norway is low

The value of cash as a share of M1 (the value of the general public’s means of payment holdings) has declined over a long period. Thirty years ago, cash accounted for over 17% of M1 but accounted for approximately 1.4% in 2024. This is very low in a global context. Nominal values have also shown a decline over the past ten years. In 2024, the value of cash in circulation was 23% lower than in 2015. The “cash paradox” that is common in many other countries, which is when the amount of cash in circulation increases even though cash payments decline, has not been observed in Norway.

In 2024, the amount of cash in circulation averaged just above NOK 38.5bn. In addition to a decline in the average amount for the year, seasonal variations have been less pronounced in recent years. However, the amount of cash in circulation does not provide an indication of how often cash is used for payments. To shed light on this, Norges Bank conducts an annual survey where a sample of Norwegian households are asked about recent payments. In 2025, this survey showed that 2% of respondents reported using cash for their most recent payment. This makes Norway one of the countries with the lowest cash usage in the world. (For more detailed information on this subject, see Retail Payment Services 2024.)

Norges Bank and banks are responsible for ensuring that cash is available

Norges Bank is responsible for meeting the general public’s demand for cash both in normal times and in crisis situations, by supplying banks with cash from five central bank depots across Norway. To address more severe crisis scenarios, Norges Bank has modified and strengthened its cash contingency arrangements in recent years, inter alia in terms of both volume and geographic distribution of cash. For more detailed information about Norges Bank’s cash handling activities, see Setlar og Myntar Årsrapport [the Notes and Coins Report] (in Norwegian only).

Banks are responsible for the further distribution of cash to their customers. Section 16-4 of the Financial Institutions Act stipulates: “Banks shall, in accordance with customer expectations and needs, accept cash from customers and make deposits available to customers in the form of cash”. This duty means ensuring that private individuals are sufficiently able to withdraw and deposit cash, and that businesses must be able to access change and to deposit cash revenue. This includes both sufficient geographical availability and other necessary functionality. Section 16-7 of the Financial Institutions Regulation stipulates that this obligation also applies when demand for cash has increased as a result of disruptions in electronic payment systems. The obligation applies to all Norwegian banks and can be met under the auspices of the banks themselves or through an agreement with other cash service providers (cf Section 16-8 of the Financial Institutions Regulation).

The provision of cash services is vulnerable and has certain weaknesses. Norges Bank has previously pointed out that the situation is not satisfactory for business customers with large volumes of cash.3

In-store cash services (KiB), a service for cash deposit and withdrawal available in approximately 1450 of NorgesGruppen’s grocery stores, now accounts for a substantial portion of banks’ cash services. The solution requires the use of a BankAxept card and PIN code and depends on functioning POS terminals and electronic systems. The KiB services are largely adequate for most consumers but are only available to BankAxept cardholders. The solution also fails to meet business sector needs for change and larger volume deposits.

The cash handling companies Nokas and Loomis play a key role in the cash supply chain. They account for most cash handling between central bank depots and public services. They also provide their own cash services in the form of ATMs, night safes and other cash handling services directly with the business sector, which includes providing change and collecting cash revenue and ensuring that business customers can deposit their cash revenues into their bank accounts.

The fact that most cash handling processes and cash services are carried out by entities that are not legally obligated to do so constitutes a vulnerability. The responsibility of banks to supply cash applies regardless of a well-functioning service provider market. Consequently, banks must be prepared to establish other solutions to meet their obligations if these entities were to reduce or discontinue their services.

A more preferable situation would be if banks were to collectively secure satisfactory cash services across Norway, so that cash could fulfil its functions without detailed regulation. In Norges Bank’s view, if banks do not find satisfactory solutions themselves, more detailed regulation should be drawn up.

Focus on contingency situations

In Norway, payments are primarily processed digitally, and electronic contingency arrangements are the first line of defence in the payment system. However, cash also remains an important part of overall payment system contingency arrangements.

BankAxept has a backup solution that kicks in, for example, when POS communication fails. It is a weakness in terms of contingency preparedness that KiB services do not function when the BankAxept backup solution kicks in.4 This means that a large part of the ordinary cash supply is disrupted when POS terminals are off line, making it difficult to obtain cash for purchases in shops that are not part of the backup solution.

In NOU (Official Norwegian Reports) 21:2024, the Payment Commission recommends that in severe crises situations, it should be possible to deposit and withdraw cash through the KiB solution even when the BankAxept backup solution is in use. Norges Bank agrees that this could be a useful solution in such situations. At the same time, banks’ obligation to supply cash services also applies in less severe crisis situations.

Cash’s ease of use

In 2024, the Storting (Norwegian parliament) passed legislative amendments to the provisions of the Financial Contracts Act relating to consumers’ right to pay with cash. The amendments were largely clarifications of existing rules but are also considered to have strengthened this right.

According to the amendments, consumers will be able to pay with cash at points of sale where a business regularly sells goods or services to consumers, provided that goods or services can be paid for with other means of payment at the point of sale or in the immediate vicinity. Exceptions are made for sales of goods from vending machines, sales in unmanned sales premises and sales in premises to which only a limited group of persons have access. Furthermore, an amount limit of NOK 20,000 has been set. Separate provisions have also been adopted, so that separate rules can apply for passenger transport services.

The amendments also provided a legal basis for imposing infringement fines. In line with this, the Ministry of Children and Families has amended assessment regulations so that from 1 May 2025, businesses risk infringement fines in accordance with these regulations if they refuse to accept cash payments from customers.

Norges Bank is of the opinion that the clarification was important for ensuring that cash can continue to fulfil its functions in the period ahead, and that the amendments were appropriate given current circumstances and needs. The amendments emphasise the need for cash services at retail outlets.

Cash payment should remain free of charge

Norges Bank is generally of the opinion that merchants and users should be incentivised to choose the most cost-efficient solutions, for example by presenting consumers in a payment situation with the costs of the various payment instruments. However, there are various factors and considerations that complicate whether to charge fees at the time of payment.

According to the Payment Commission in NOU (Official Norwegian Reports) 21:2024, cash payments should remain free of charge at the time of payment because of different considerations such as those related to financial inclusion. Not everyone has access to the digital payment system, meaning that their only choice of payment instrument is cash. Furthermore, the Commission points out that the consideration of cash’s role in a contingency situation must be given weight. The Commission also points out that the Financial Contracts Act imposes restrictions on merchants’ ability to charge payment fees.

Norges Bank supports the Commission’s assessments and conclusion that cash payments should continue to be free of charge. In particular, charging fees seems unreasonable for carrying out ordinary purchases in a contingency situation where cash is the only option. Costs related to the contingency role of cash in society should be distributed among all users, regardless of the means of payment they otherwise use on a day-to-day basis.