FSR 2025 H2

In a nutshell

Continued heightened risk of weakened financial stability

The Norwegian financial system is resilient. At the same, the outlook for the global economy is highly uncertain, in particular due to geopolitical tensions and changes in global trade policy. In a global, interconnected financial system, new shocks may quickly impact the Norwegian financial system.

Lower household debt-to-income ratios

Norwegian households are highly indebted, but debt growth has been slower than income growth in recent years. Debt-to-income (DTI) ratios have declined the most for households with the highest level of debt. This contributed to somewhat lower household sector vulnerabilities.

In the years following the pandemic, high inflation and higher interest rates have led to tighter finances for many households, but most households have been able to service debt and cover normal living expenses with current earnings. Many households also have accumulated savings.

Over the past two years, wage growth has outpaced inflation, and residential mortgage rates have edged down slightly in 2025. This has strengthened household purchasing power and improved debt-servicing capacity.

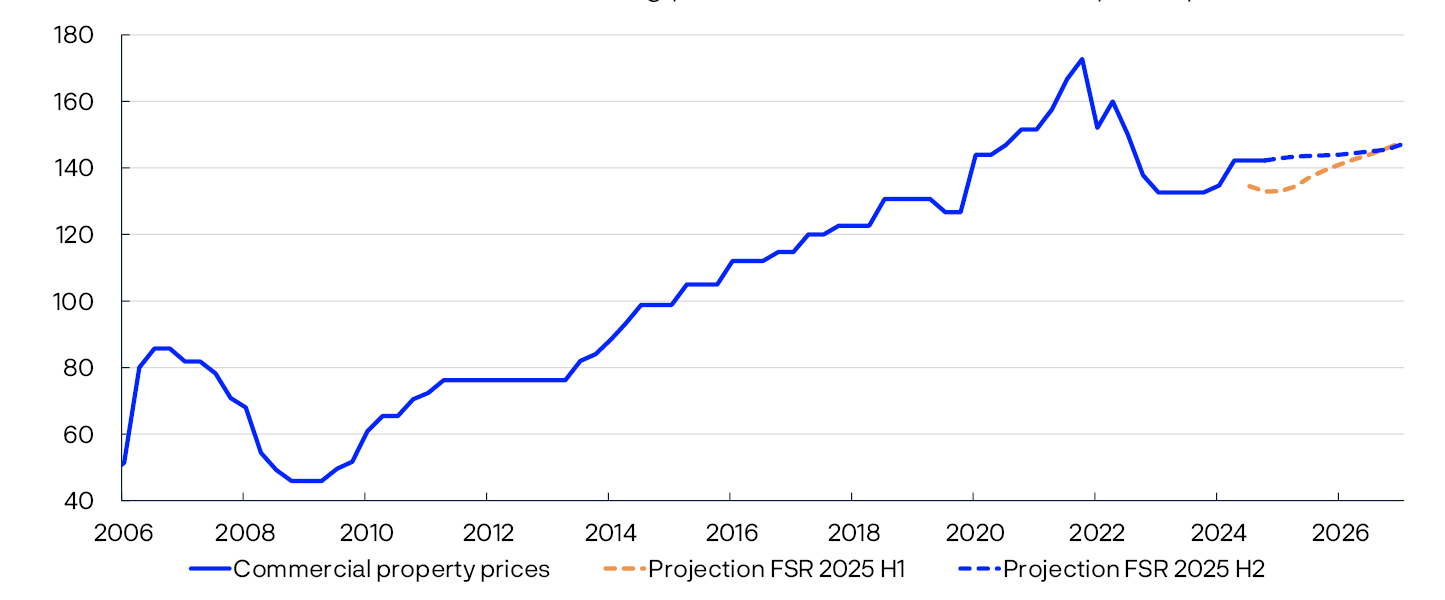

Developments in commercial real estate are stable but still a challenge for real estate developers

Banks have substantial commercial real estate (CRE) exposures. Higher interest rates and lower property values have posed a challenge for CRE firms, but high employment and increased rental income have enabled most firms to cover expenses with current earnings, while for real estate developers, this is still a challenge. Housing construction is low, and earnings have fallen. Somewhat lower interest rates and higher house prices may boost profitability ahead, but Norges Bank still expects somewhat higher bank losses on loans to real estate developers.

Banks are resilient

Resilient banks are important for financial stability. Norwegian banks are solid, have ample liquidity and low losses. Firms and households have ample access to credit. Maintaining financial system resilience is important. The countercyclical capital buffer requirement makes a contribution in this regard.

The Committee’s assessment

Norges Bank’s Monetary Policy and Financial Stability Committee considers the Norwegian financial system to be robust. Households and firms have solid debt-servicing capacity. Debt-to-income (DTI) ratios have declined over time across households, and vulnerabilities associated with high indebtedness have been reduced somewhat. At the same time, there is still a heightened risk of events that could weaken financial stability. It is important to maintain the resilience of the financial system so that vulnerabilities do not amplify an economic downturn.

Continued heightened risk of events that could weaken financial stability

The balance of risks for the global economy is marked by geopolitical tensions and changes in global trade policy. The effects of higher tariffs remain uncertain. They will likely dampen global growth, but so far do not appear to have significantly affected economic activity, neither in Norway nor among Norway’s main trading partners. At the same time, the framework for international cooperation appears to be more unpredictable than before.

The outlook for the global economy is highly uncertain, and the risk of unexpected events that could weaken financial stability is still higher than normal. Major equity indices have reached new peak levels, and the IMF points out that financial asset valuations appear stretched, increasing the risk of abrupt and disorderly market movements. At the same time, the interconnectedness between banks and other financial institutions is increasing, which could amplify market movements and contribute to stress spillovers in the financial system.

Changes in the security policy landscape have resulted in many European countries now increasing defence investment. At the same time, expenses related to climate transition and an ageing population are rising. Budget adjustments will be particularly difficult in countries with weak government finances and already high government debt. In a turbulent world, the risk of targeted cyberattacks and other operational disruptions also increases. If cyberattacks impact critical functions or cause a broad-based loss of confidence, they could pose a threat to financial stability.

The cryptoasset market is also growing rapidly, particularly stablecoins. Stablecoins are designed to maintain a stable value relative to reference assets, such as the US dollar, and are often backed by reserves in the form of bank deposits and liquid securities. However, if confidence is lost, stablecoins may face a redemption run. Rapid sales of underlying assets can trigger liquidity stress that can spill over to other markets. Should strong stablecoin growth persist, stablecoins may become a source of systemic risk in the global financial system. The new Markets in Crypto-Aassets Regulation (MiCA) contributes to reducing systemic risk. Globally, however, there is still a need for further regulatory developments and cooperation.

In a global, interconnected financial system, new shocks may quickly impact the Norwegian financial system. Financial system vulnerabilities could amplify a downturn in the Norwegian economy and lead to bank losses.

Lower household debt-to-income ratios

The high indebtedness of many households is a key financial system vulnerability as it increases the risk of sharp consumption cutbacks should interest rates rise, household income decline or house prices fall markedly. Should such multiple shocks coincide, consumption cutbacks could weaken firms’ earnings and debt-servicing capacity. Analyses in this Report show that households with the highest DTI ratios cut back on consumption more than other households when interest rates rise and house prices fall markedly.

According to Finanstilsynet’s (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway) residential mortgage lending survey for 2025, DTI ratios increase somewhat with new mortgages, and a higher share of new mortgages are issued with loan-to-value (LTV) ratios close to 90%. Developments must be viewed in the light of the increase in the Lending Regulations’ maximum LTV ratio requirement at the turn of the year from 85% to 90%. At the same time, total household debt has risen less than income in recent years, and analyses in this Report show that DTI ratios have declined broadly across households and the most for those with the highest ratios. In Norges Bank’s assessment, Norwegian household vulnerability related to high debt has been somewhat reduced. This vulnerability may increase again if looser financial conditions result in rapidly rising house prices and debt.

Higher interest rates and high inflation tightened household finances in the years following the pandemic. However, most households have been able to service debt and cover normal living expenses with current earnings by a solid margin. Many households also have financial buffers. Over the past two years, wage growth has outpaced inflation, and residential mortgage rates have edged down slightly in 2025. This has strengthened household purchasing power and improved debt-servicing capacity.

For a long time, house prices rose faster than household income. At the same time, the owner-occupancy rate has remained firm, Nevertheless, there are signs that households’ response to higher house prices has changed. The analyses in this Report indicate that housing affordability has fallen over time, particularly in urban areas, and that individuals with relatively low income, low parental wealth or both, postpone home purchases.

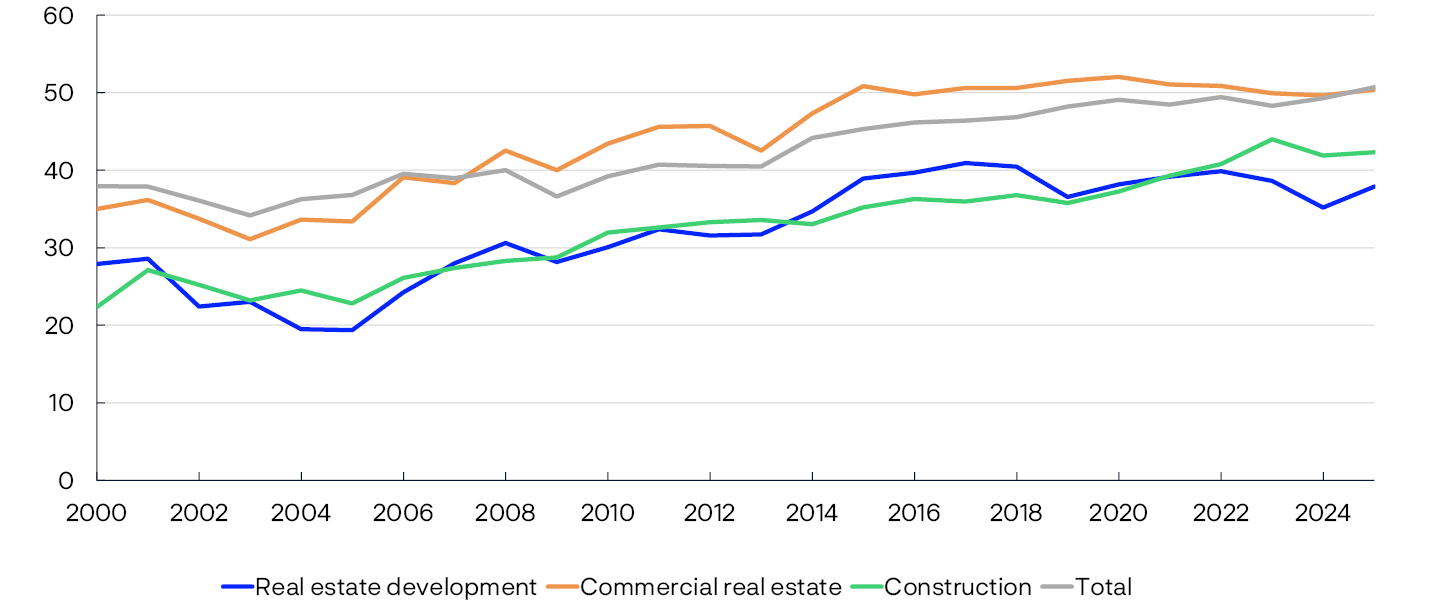

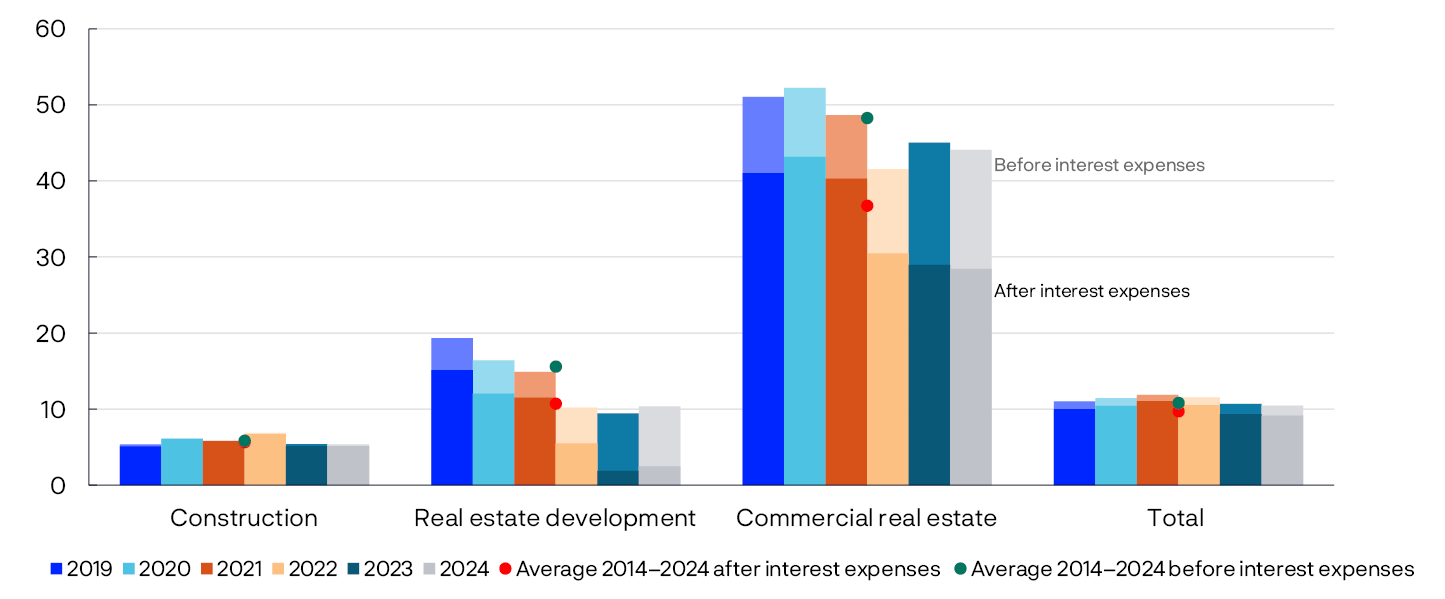

In the CRE market, developments are stable, while low construction activity continues to pose challenges for real estate development

The overall financial position of Norwegian firms was stable through 2024, after having weakened somewhat in pace with the rise in interest rates in recent years. Overall, Norwegian firms are robust. The higher US tariffs introduced to date likely have a limited direct impact on activity in Norwegian firms.

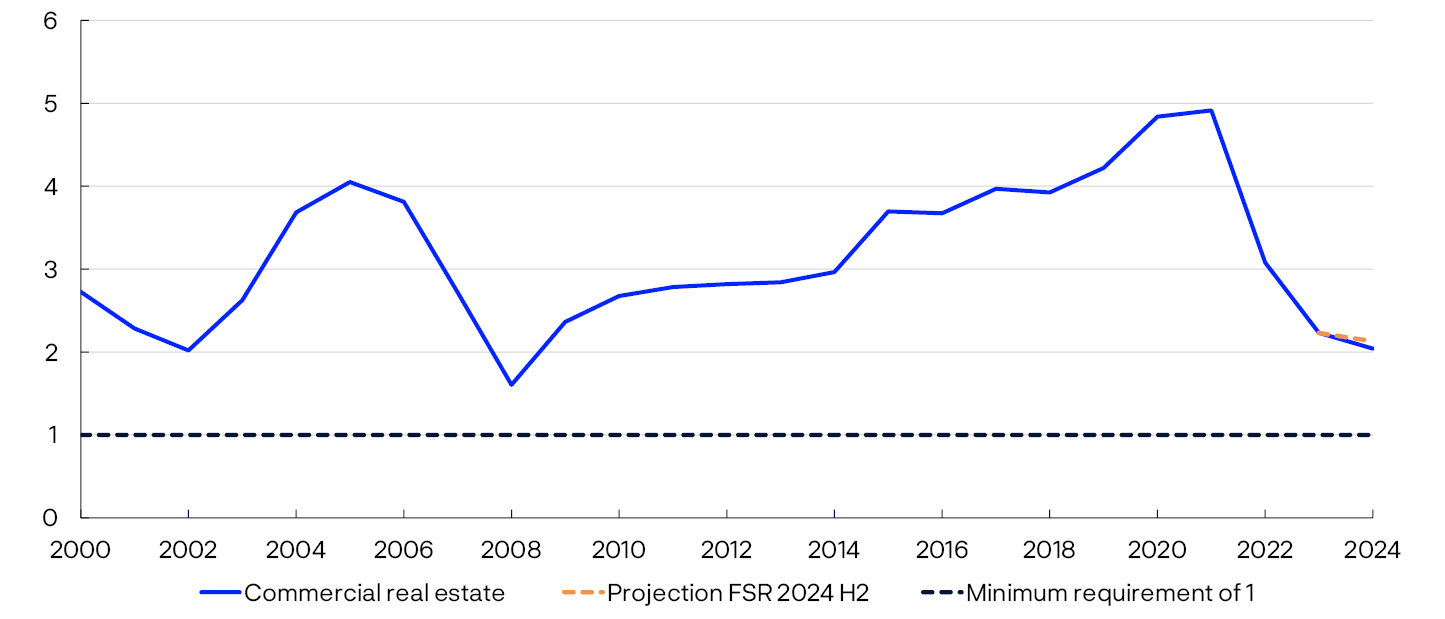

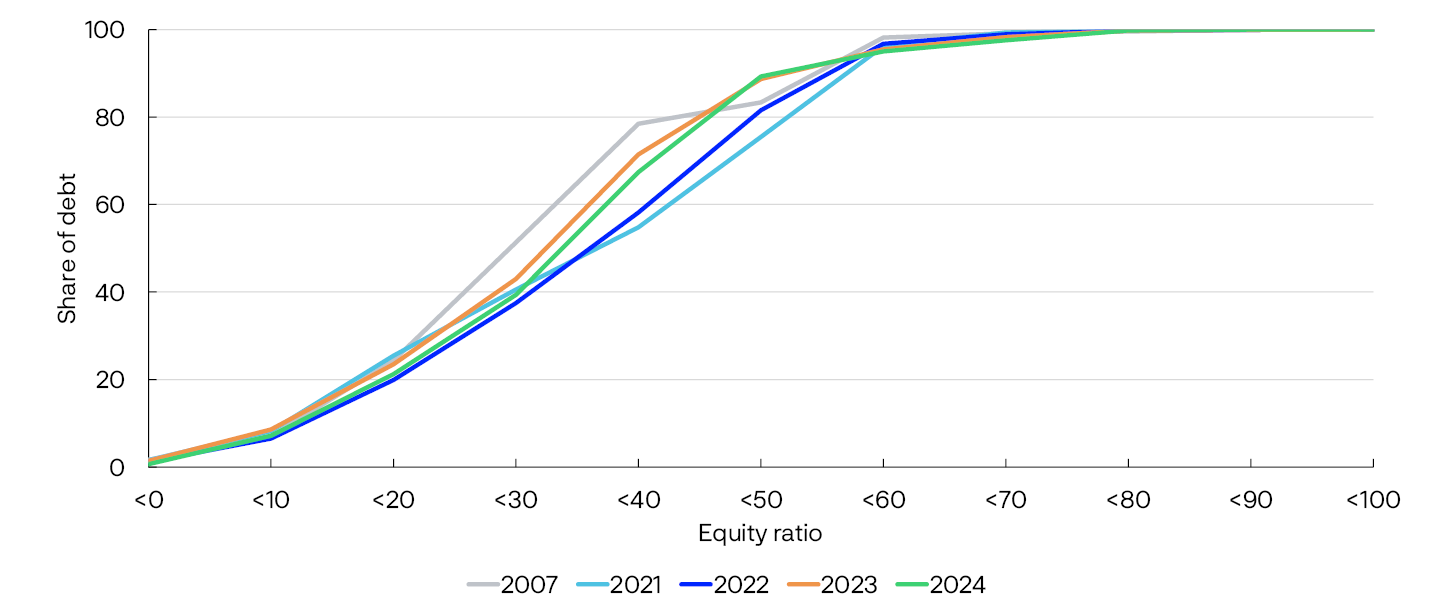

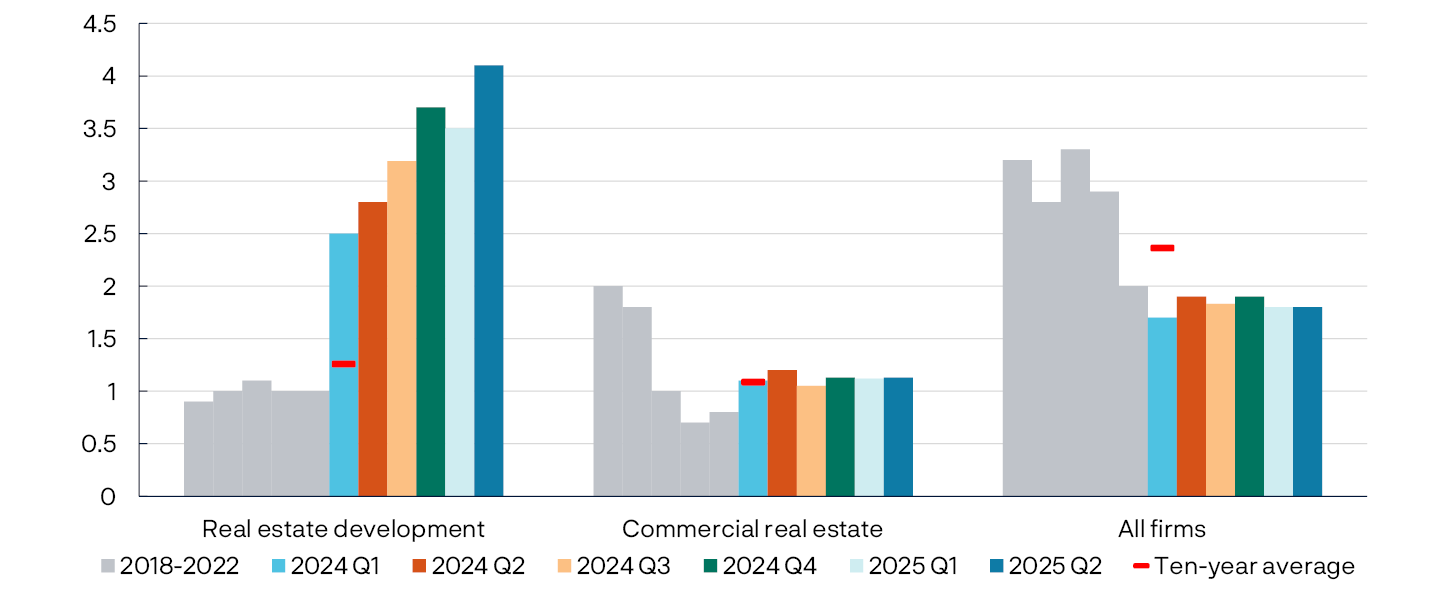

Norwegian banks’ particularly high CRE exposure is a key financial system vulnerability. The rise in financing costs and lower property values have weighed down on both the profitability and solvency of CRE firms in recent years. However, high employment and growth in rental income enable most CRE firms to cover high interest expenses with current earnings. In recent years, a number of firms have sold real estate or raised equity to improve their financial positions, and sector solvency as a whole improved somewhat in 2024. Credit premiums for bank and bond financing have fallen further since the previous Report, reducing financing costs for loans that have to be refinanced.

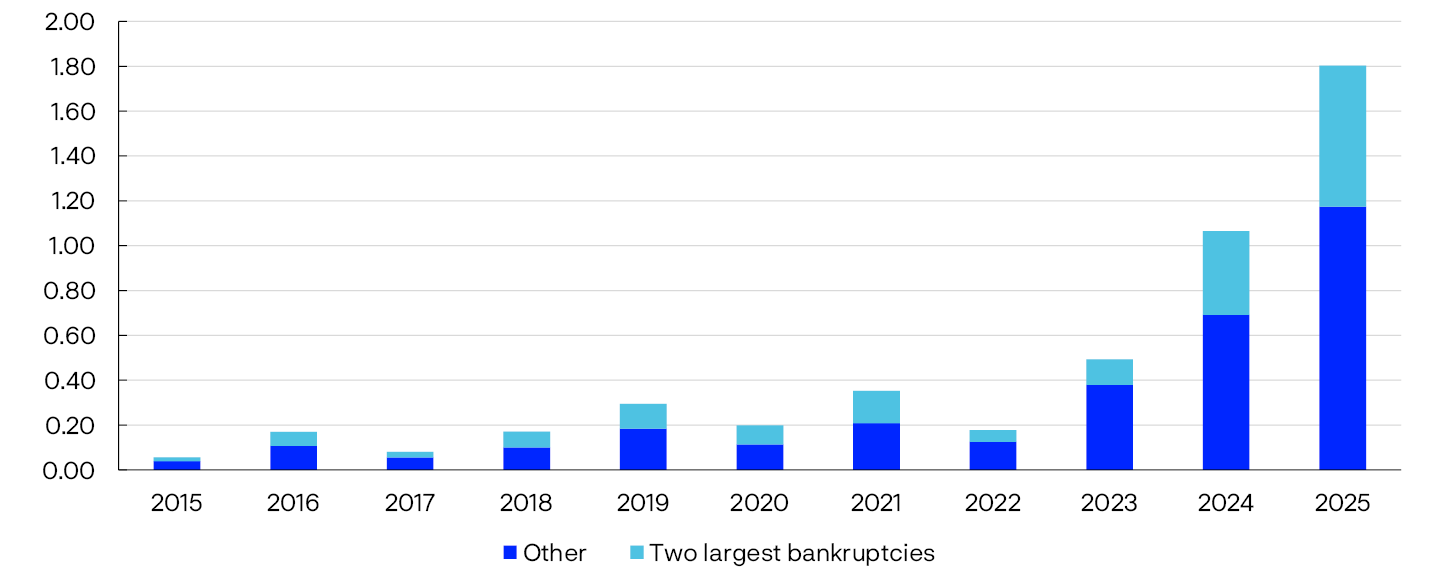

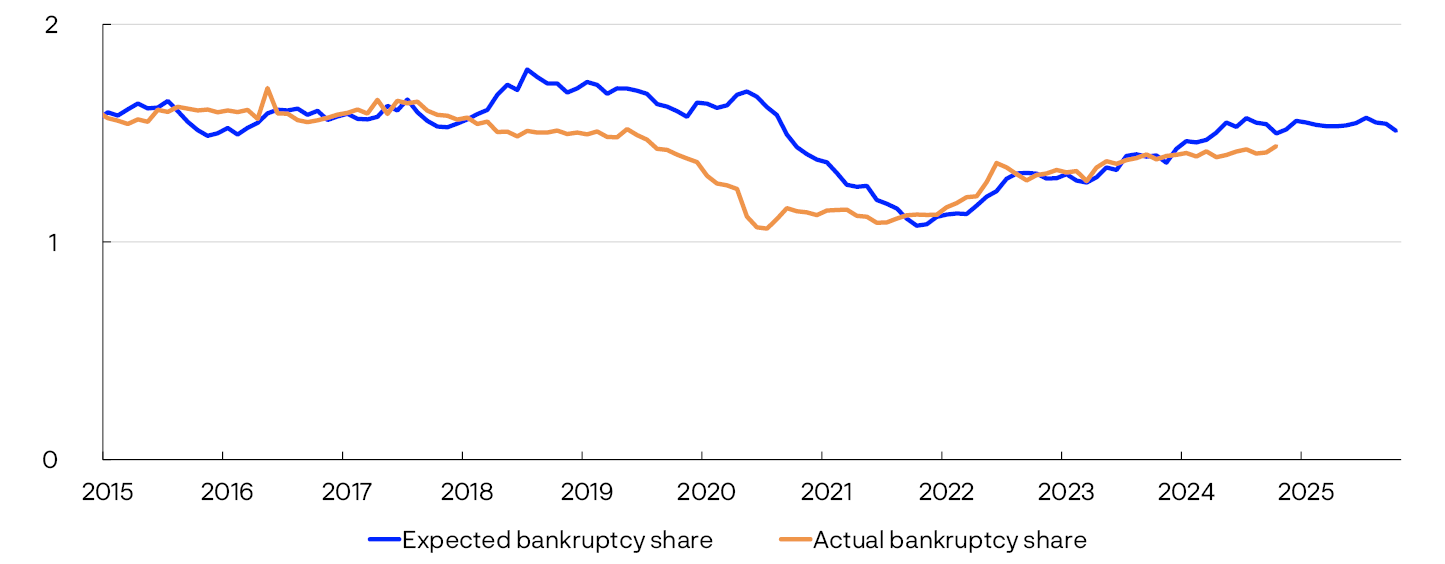

The share of bankruptcies among Norwegian firms has risen in recent years, reflecting a normalisation following an unusually low number of bankruptcies during the pandemic. Bankruptcies in most sectors are now at approximately the same level as the average for the past decade.

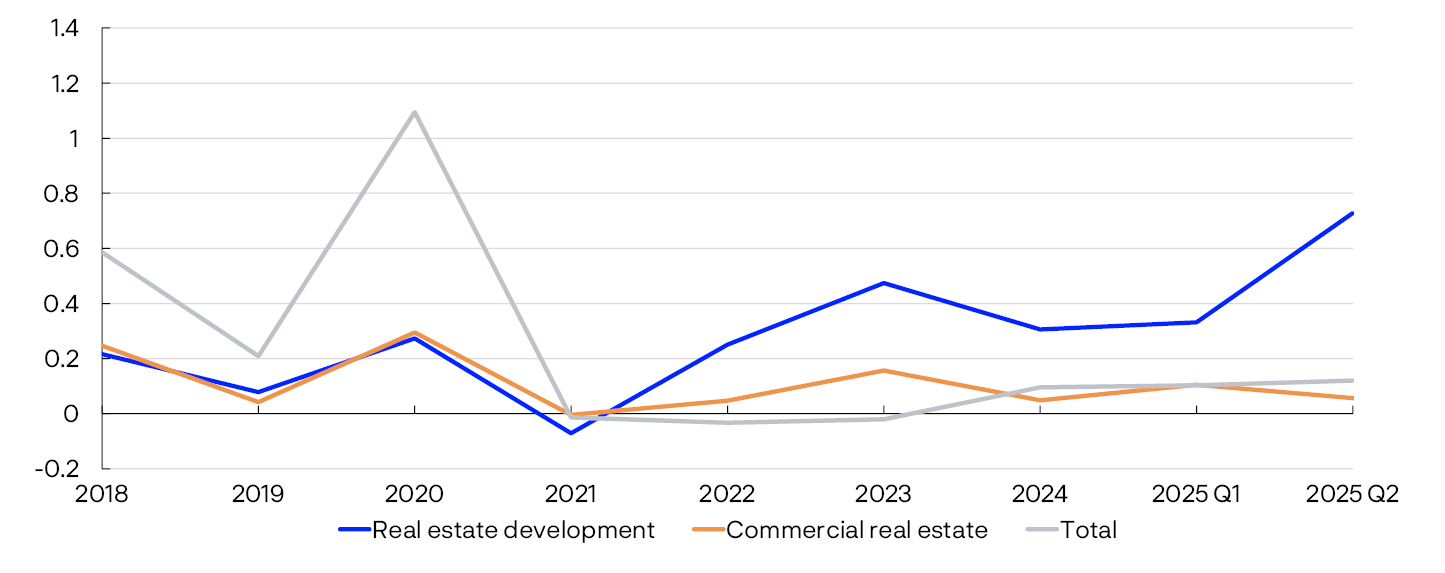

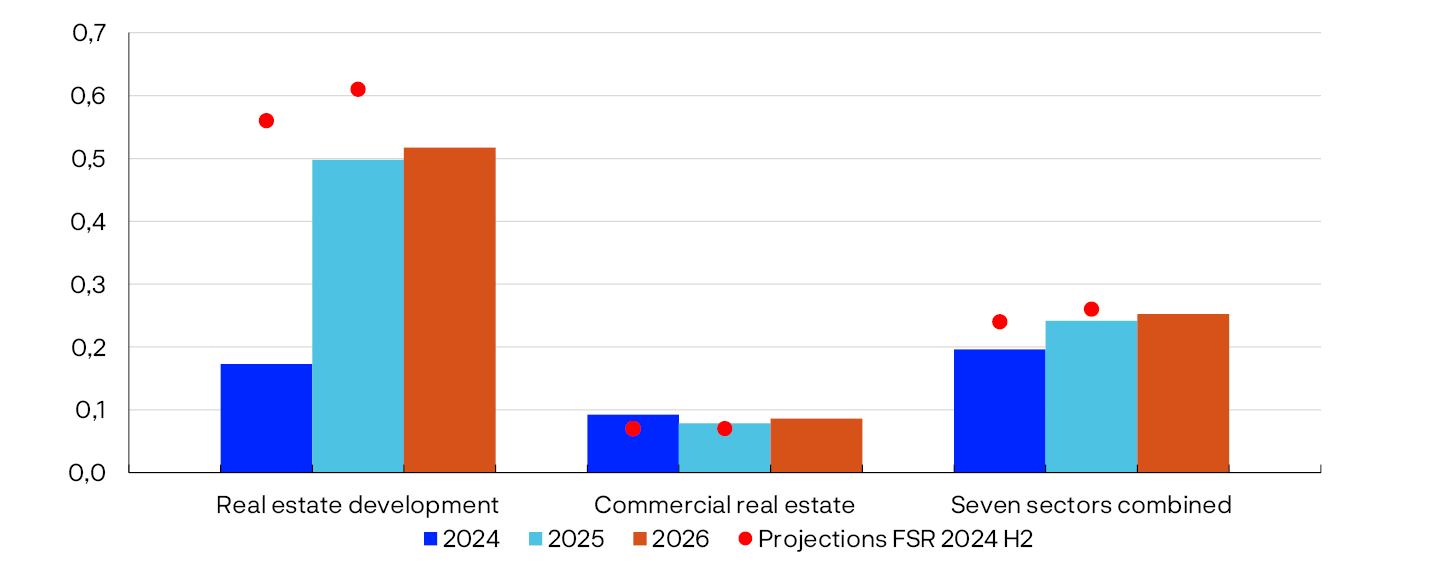

However, bankruptcies in real estate development have risen markedly. Construction activity is low, and earnings have fallen. In Norges Bank’s lending survey for 2025 Q3, half of banks report an increased risk of default and breach of the terms of loan covenants. Looking ahead, somewhat lower financing costs and higher house prices are likely to boost profitability in construction and may lead to more projects being realised. Somewhat higher bank losses on exposures to the construction sector are expected in the year ahead.

Norwegian banks are solid

Banks are the most important source of financing for most households and firms, which is why resilient banks are key to financial stability. Norwegian banks satisfy capital and liquidity requirements by a solid margin and have ample access to both deposits and wholesale funding.

Banks’ profitability is the first line of defence against losses. Norwegian banks are highly profitable, primarily reflecting high net interest income and low credit losses. Looking ahead, lower interest rates are expected to reduce net interest income somewhat.

Financial system resilience is strong and must be maintained

Both in Norway and internationally, the financial system has proven resilient to major market shocks, high inflation and higher interest rates in recent years, partly reflecting global regulation standards that were put in place following the 2008 financial crisis. In a number of countries there is now increased pressure to ease banks’ capital requirements. There are good reasons to explore opportunities to simplify complex and comprehensive regulations, but this must not be at the expense of maintaining financial system resilience.

The Lending Regulations contribute to this resilience by setting limits on banks’ credit standards and dampening the build-up of household sector vulnerabilities. On 1 January 2025, the Regulations were made permanent. Permanent Lending Regulations will contribute to predictability and counter future deterioration of banks’ credit standards.

Norwegian banks’ capital buffer requirements reflect the vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system and bolster resilience. In the event of a sharp downturn, buffer requirements can be reduced to mitigate the risk of tighter bank lending. The solvency stress test in Financial Stability Report 2025 H1 shows that banks can absorb large credit losses, while maintaining lending.

Norges Bank sets the countercyclical capital buffer rate each quarter. At its meeting on 5 November 2025, the Monetary Policy and Financial Stability Committee decided to keep the countercyclical capital buffer rate unchanged at 2.5%.

Ida Wolden Bache

Pål Longva

Øystein Børsum

Ingvild Almås

Steinar Holden

1.1 Heightened risk of weakened financial stability

Uncertainty surrounding the global economic outlook remains high

The balance of risks for the global economy is marked by geopolitical tension and changes in global trade policy, and the uncertainty surrounding the growth outlook remains high. Higher tariffs are likely to dampen global growth but so far appear to have had little material impact on economic activity in Norway or among Norway’s main trading partners. Trade agreements between the US and several of its main trading partners have provided greater clarity, but the effects of the tariffs on supply chains and international inflation in the slightly longer term remain to be seen. The uncertainty that is clouding global trade policy and cooperation will likely persist. For a small, open economy such as Norway’s, a multi-lateral, rules-based world order is an important foundation for economic and financial stability.

Uncertainty and financial stability

Uncertainty about global economic developments may impact financial stability through both the real economy and financial markets. Households and firms may postpone consumption expenditure and investment when uncertainty surrounding the economic outlook is elevated, which may in turn reduce corporate earnings and debt servicing capacity. This may result in higher credit risk and amplify an economic downturn through tighter bank credit standards. Furthermore, changes in market sentiment may have a greater impact on financial markets when uncertainty is high. This could contribute to funding and financing problems for governments, banks and firms. Heightened uncertainty may also reduce market liquidity, leading to less efficient redistribution of risk and capital and weakening banks’ ability to realise securities from their liquidity reserves without pushing down market prices and thus the value of their liquidity reserves.

In its October Global Financial Stability Report, the IMF emphasises the heightened risk of weakened global financial stability. This must be viewed in the context of multiple ongoing military conflicts and heightened tensions between countries. The IMF also points out that financial asset valuations appear stretched and that increasing interconnectedness between banks and non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) could amplify market movements and contribute to stress spillovers in the financial system. Other developments emphasised by the IMF are growing fiscal deficits and borrowing requirements in many countries. The European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) also assesses that there is a heightened risk of weakened financial stability in the EU.1

Norwegian market participants consider geopolitical tensions and cyberattacks to be the main sources of risk in the Norwegian financial system

In Norway, unemployment has increased somewhat over the past year, and capacity utilisation in the economy has declined to a normal level. At the same time, Norway’s financial system is robust. Household debt-servicing capacity is solid, and on the whole, Norwegian firms are financially sound (see Sections 2 and 3). Banks are also resilient (see Section 1.2).

However, new shocks may have consequences for both the real economy and the financial system. In a turbulent world, there is heightened risk of targeted cyberattacks and other operational disruptions. Attack surfaces expand as technology advances and financial system interconnectedness deepens. If cyberattacks impact critical functions or cause a broad-based loss of confidence, they could pose a threat to financial stability (see Financial Infrastructure Report 2025).

Norges Bank’s systemic risk survey conducted in October shows that Norwegian financial market participants consider geopolitical tensions and cyberattacks to be the main sources of risk to the Norwegian financial system (Chart 1.1). Overall, respondents assessed that the probability of an incident having a substantial impact on the financial system in the course of the next three years has increased somewhat over the last six months. However, they are highly confident that the Norwegian financial system will remain stable. For an overview of the most important vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system, see “Key vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system”.

Norges Bank’s Systemic Risk Survey from October 2025. Which source of risk do you consider most likely?

Financial markets are vulnerable to shocks

The past few years have been marked by a number of events that have led to considerable uncertainty and market volatility. This has also impacted Norwegian financial markets.

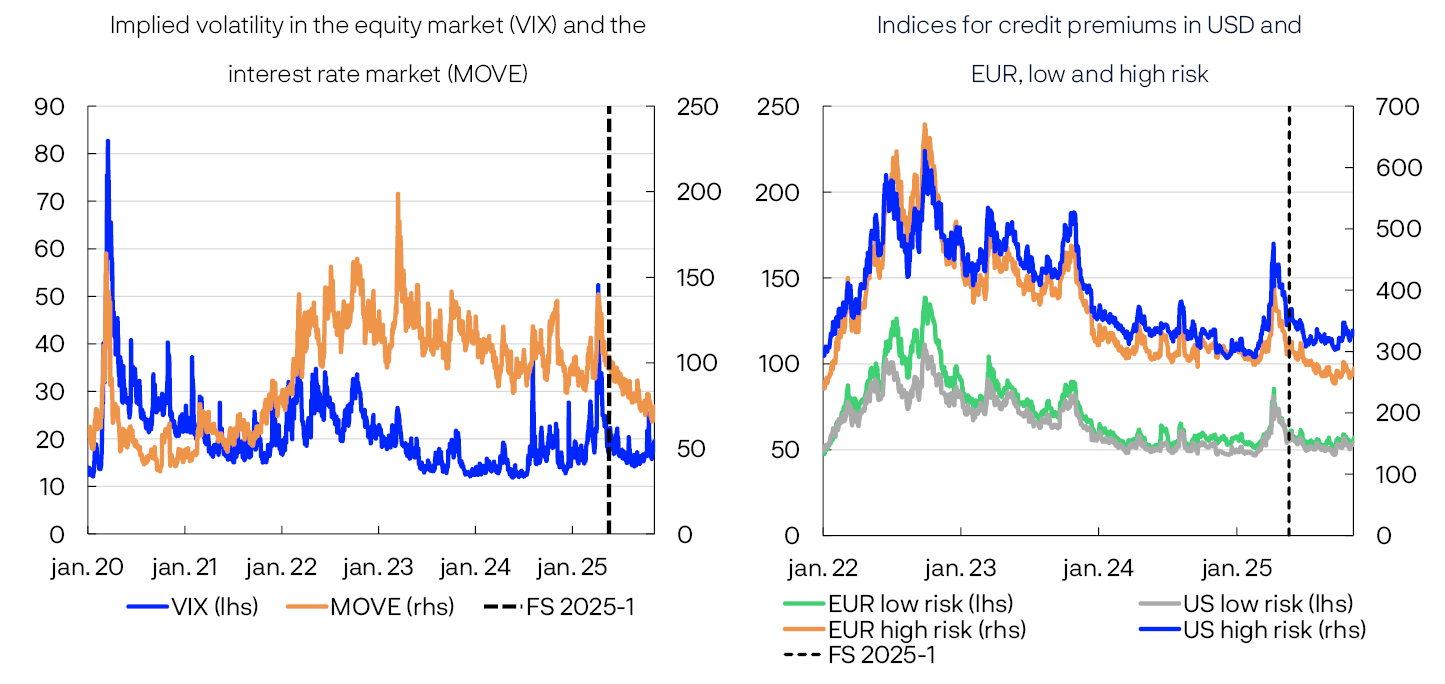

Major trade restrictions and trade policy uncertainty led to heightened financial market volatility in April. Global financial conditions have since eased, and market volatility indicators have fallen (Chart 1.2).

Implied volatility in the equity market (VIX) and the interest rate market (MOVE) / Indices for credit premiums in USD and EUR, low and high risk

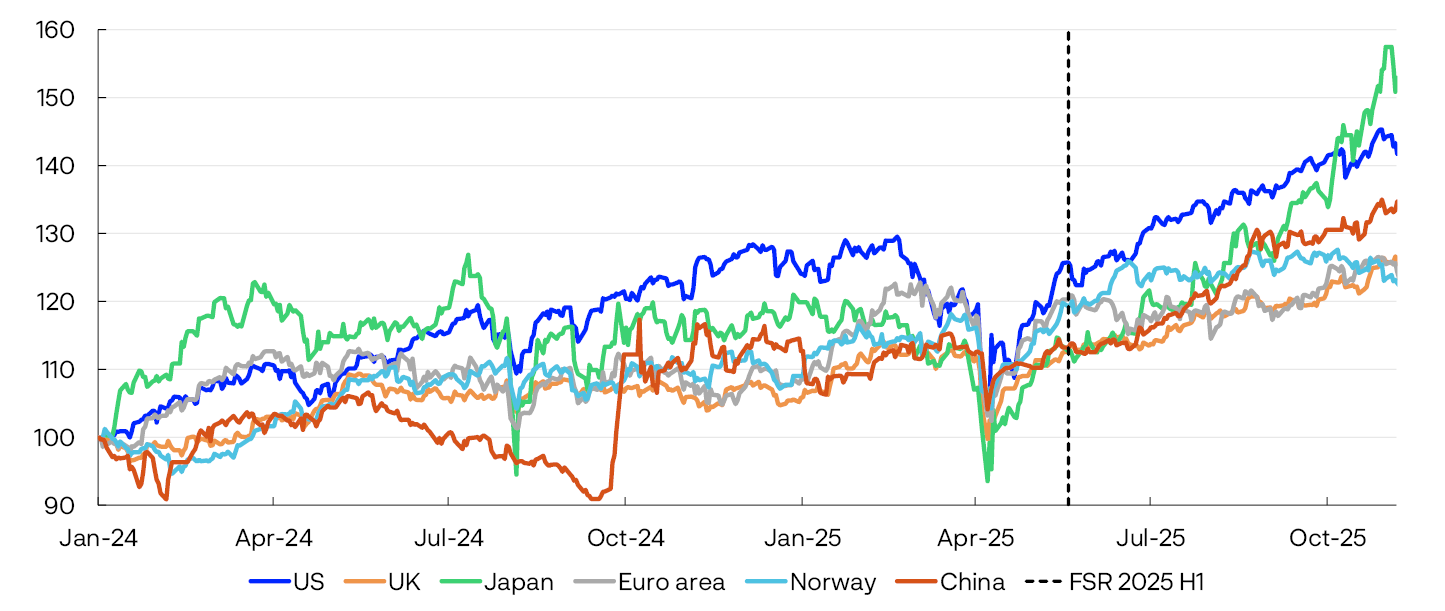

A number of major equity indices have reached new highs, and credit premiums have fallen following the market turbulence this spring (Chart 1.3). The substantial rise in equity prices over the period can partly be explained by slightly higher earnings expectations among firms and higher rate cut expectations in the US.4 However, these factors cannot fully explain the rise in equity prices, indicating that equity risk premiums have fallen. In isolation, this raises the risk of abruptly falling asset prices and rising credit premiums in response to new information.

Global equity indices. January 2024 = 100

In the US, the rally in equity markets is driven by technology and communication companies, which have announced major investment in, among other things, AI and data centre developments. The seven largest companies in the US S&P500 benchmark index account for a steadily increasing share of market value6, and developments in the index are therefore heavily influenced by a small number of companies in the same sector. Technology shares on Oslo Børs have also surged but make up a relatively small share of the benchmark index. In Norway, energy equities have fallen in pace with lower oil prices, while consumer goods equities have increased.

Turbulence in international financial markets can result in a rise in the risk premiums paid by banks on wholesale funding, both in Norway and in other countries. As Norwegian banks have high credit ratings and are well capitalised, this may better insulate them against international market turbulence. At the same time, much of Norwegian banks’ funding is raised abroad and well-functioning international financial markets are therefore important to them.

The US dollar weakened following market turbulence this spring

The US dollar plays a key role in the global financial system and influences, among other things, conditions for financing and the pricing of risk, also in Norwegian markets. Previously, the US dollar has appreciated during market turbulence and thereby helped dampen the depreciation of US assets owned by US investors. However, in connection with the period of market turbulence this spring, the US dollar depreciated sharply together with an abrupt fall in equity prices. Since then, the decline in asset prices and premiums has been reversed, but the dollar has not appreciated. The IMF highlights several reasons for the dollar depreciation, including concerns over US government finances and political uncertainty.7 Furthermore, the IMF points out that while there has so far been little sign of investors withdrawing from the US, many have strengthened their currency hedging positions to reduce the risk of losses on dollar exposures. The increase in hedging has likely contributed to the dollar depreciation.

Norwegian banks have largely hedged foreign exchange risk. A weakening of the US dollar could nevertheless impact bank liquidity by increasing collateral requirements in currency swaps and requiring them to surrender liquidity to counterparties in these agreements. If the US dollar depreciates sharply and suddenly, collateral requirements are not likely to pose a liquidity challenge to Norwegian banks.

Increased supply and lower demand for long-term government bonds may push up long-term yields

The government bond market is important for financial stability. Government bonds serve, among other things, as a benchmark for other asset prices and as collateral for loans and derivatives transactions. In many countries, banks have large holdings of government bonds. If countries’ credit ratings are downgraded, banks’ credit quality could deteriorate, which may increase banks’ funding costs and result in tighter credit standards for households and firms.

A number of European countries are now increasing defence expenditure sharply. At the same time, expenses related to climate transition and an ageing population are rising, which will likely lead to larger fiscal deficits and an increased supply of government bonds. This may push up the premiums required by investors to hold long-dated rather than short-dated bonds, measured as the term premium. Pressure on government budgets, particularly in highly indebted countries, may erode fiscal space to address future problems and financial downturns.

Other developments may also have contributed to higher term premiums in the government bond market. In recent years, a number of the largest central banks have started to reverse their asset purchase programmes, ie they let their bond portfolios mature and no longer purchase government securities. At the same time, the transition from defined-benefit to defined-contribution occupational pension schemes in a number of European countries has resulted in lower demand from pension funds and insurance companies for long-term government bonds to meet their long-term obligations. Some funds will likely also have to sell significant volumes in a transitional period, which will increase the supply of government bonds.8 The uncertainty related to how lower demand will be balanced against a continued high and increasing supply of government bonds may intensify volatility in fixed income markets ahead and higher long-term yields.

Also in Norway, the transition to defined-contribution pension schemes has reduced the volume of Norwegian pension funds’ holdings of long-term bonds than was previously the case. The shift towards other assets, such as equities and shorter-dated bonds, has been gradual.

Non-bank financial institutions may amplify market turbulence

Important functions in the financial system are performed by non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs)9. They play a key role in channelling capital, sharing risk and contributing to financial stability. These institutions can assume, transform or transfer risk from the banking sector to market participants that are better positioned to manage such risk. Increasing interconnectedness between banks and less regulated NBFIs may, however, be a source of financial system vulnerabilities.

Internationally, NBFIs are playing an increasingly prominent role in the government bond market and in credit intermediation to non-financial corporates. In many countries, including Norway, the total assets held by NBFIs have grown more than the total assets held by banks. So far, direct lending from NBFIs to Norwegian non-financial corporates is limited (see “Who lends to Norwegian non-financial corporates?”).

At the same time, NBFIs have direct connections to banks through ownership of each other’s equity capital and debt instruments or by being counterparties in derivatives transactions (see Section 2.3 in Financial Stability Report 2025 H1. In a crisis, these close connections can amplify market movements and contribute to the transmission of stress to other parts of the financial system. In October, uncertainty about the credit quality and potential losses on securitised US corporate loans, which are held by both banks and NBFIs, led to a fall in global equity markets. This also illustrated the heightened attention in financial markets to connections between banks and NBFIs.

Norwegian banks’ direct exposure to the Norwegian NBFI sector is low compared to banks’ total assets, but the sector is important for banks’ wholesale funding. NBFIs hold, among other things, a substantial share of bonds issued by banks and mortgage companies. Selling pressure may arise if NBFIs, such as hedge funds, need liquidity, for example as a result of substantial collateral requirements in derivatives contracts or large redemptions of fund units. This may lead to a fall in bond prices and amplify market stress, as seen during the pandemic in 2020.

Foreign hedge funds hold an increasing share of covered bonds issued in NOK and use repurchase agreements with Nordic banks to obtain leverage. Leveraging enables the hedge funds to achieve high returns but also makes the funds vulnerable to events that may force them to conduct fire sales of covered bonds. This may lead to stress in the covered bond market, which may spill over to other parts of the credit market (see Financial Stability Report 2025 H1.

Amendments to the regulations for alternative investment funds (AIFs), AIFMD 2.0, allow such funds to engage in lending to consumers and non-financial corporates (see “Regulatory amendments permit alternative investment funds to engage in lending”). A broader range of financing sources can, in principle, strengthen financial stability by spreading credit risk among multiple market participants. On the other hand, lending through AIFs may entail vulnerabilities. Weaker reporting requirements may obscure risk and contribute to reducing transparency in credit markets.

Regulatory amendments permit alternative investment funds to engage in lending

Alternative investment funds (AIFs) are collective investment schemes that are not undertakings for collective investment in transferable securities (UCITS). AIFs pool capital from multiple investors and have a defined investment strategy. AIFs include real estate funds, private equity funds and hedge funds. Most AIFs in Norway are funds that invest capital, but an AIF can also be a private credit fund that provides direct lending. Such funds have grown rapidly in both the US and Europe.1 Private credit has been limited in Norway up to now, partly because funds require a bank or financial institution licence to engage in lending.2

In Norway, AIFs are regulated by the AIF Act, which implements the AIF Directive of 2011. In March 2024, the EU adopted amendments to the AIFM and UCITS directives, and these amendments are often referred to as AIFMD 2.0. The amendments harmonise provisions for lending from AIFs in the European Economic Area and permit lending to both consumers and firms. Member states can prohibit lending from AIFs to consumers. The Ministry of Finance has submitted a consultation proposal prepared by Finanstilsynet on how AIFMD 2.0 should be implemented in Norwegian law.3 Finanstilsynet proposes that Norway should exercise the option to prohibit lending from AIFs to consumers. AIFMD 2.0 will apply in the EU from April 2026 but can only enter into force in Norway upon incorporation into the EEA Agreement. Once the regulations enter into force, the option to provide loans through AIFs will be expanded considerably.

Private credit still accounts for a small share of overall lending globally, and overall risk is therefore considered limited. However, a growing market and forthcoming regulatory changes suggest that future developments should be monitored closely.

1 See eg ECB (2024) Private markets, public risk? Financial stability implications of alternative funding sources and Section 2 in IMF (2024) The Last Mile: Financial Vulnerabilities and Risks.

2 The ELTIF Regulation does, however, permit some forms of long-term loans, and Union Kreditt was first to launch a private credit fund aimed at commercial real estate under this framework in 2024. The European Venture Capital Fund (EuVECA) Regulation and the European Social Entrepreneurship Funds (EuSEF) Regulation also permit lending under certain stipulated terms and conditions.

3 For more information about the consultation process, see news item from the Ministry of Finance dated 8 October 2025 (in Norwegian only).

Stablecoins may give rise to systemic risk further out

Norges Bank is seeing an increasing level of interconnectedness between traditional finance and the cryptoasset market. Stablecoins, which are a part of this market, are growing rapidly and becoming increasingly connected to the traditional financial system. Such developments have contributed to raising awareness of the potential consequences for financial stability.

Most stablecoins are pegged to the US dollar and are used, among other things, as a store of value and for money transfers in countries with less well-functioning money and payment systems. This has led to concerns over currency substitution in favour of the US dollar in such countries and may weaken the effect of national policy instruments in foreign exchange, money and capital markets.10

Stablecoins are backed by bank deposits and government securities to maintain a stable value relative to the reference asset. However, if confidence is lost, stablecoins may face a redemption run. A right to redeem the stablecoin for the nominal value of the reference currency may amplify vulnerabilities as users will require early redemption while the collateral is still sufficient. Fire sales of underlying assets may lead to a fall in prices and liquidity stress that could spill over to other markets. Wider adoption may also change banks’ funding structure if retail bank deposits are replaced to a greater extent by few and larger deposits from stablecoin issuers. Few deposits from some professional market participants may lead to more volatile financing and potentially reduce banks’ capacity to provide lending to households and firms.

To date, the exposure to cryptoassets in banks and other financial institutions appears limited. The IMF emphasises that the potential systemic effects depend on whether stablecoins continue to grow.11 Stablecoins in NOK have not yet been issued, but banks in the US and Europe have shown an interest in issuing stablecoins in EUR and USD, both individually and in collaboration, see “Increased interest in stablecoins triggers need for regulation”.

1 See press release from the ESRB’s General Board meeting on 25 September 2025: Outcomes of the 59th General Board meeting of the European Systemic Risk Board – 25 September 2025

2 Based on Norges Bank’s Systemic Risk Survey from October 2025. A selection of participants in the Norwegian financial system take part, and the responses reflect the risk assessments at the time the survey was conducted.

The chart shows the source of risk considered most likely in the Norwegian financial system according to the respondents.

3 Left panel:

Period: 1 January 2020 – 5 November 2025.

Right panel:

Period: 1 January 2022 – 5 November 2025.

4 Market participants’ earnings expectations are consensus estimates for annual earnings from Bloomberg.

5 Period: 1 January 2024 – 5 November 2025.

6 The seven largest technology companies are often called “the Magnificent 7” and now account for around 35% of the market value of the S&P 500 index. They are currently Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, Alphabet/Google, Amazon, Meta and Broadcom.

8 For example, all pension schemes in the Netherlands will be converted to defined-contribution models over the next two years. This may trigger a need for Dutch pension funds to sell a substantial volume of long-term European government bonds.

9 NBFI is an abbreviation for “non-bank financial Institutions” or “non-bank financial intermediation” and includes insurance companies, investment funds and assets managers, such as hedge funds.

1.2 Norwegian banks are resilient

Banks are profitable and credit losses are low

International shocks and market stress may have consequences for the funding conditions of Norwegian banks. Banks’ funding markets have functioned well since the May Report. Risk premiums on banks’ wholesale funding have fallen somewhat, and deposit-to-loan ratios are stable. Norwegian banks satisfy capital and liquidity requirements by a solid margin.

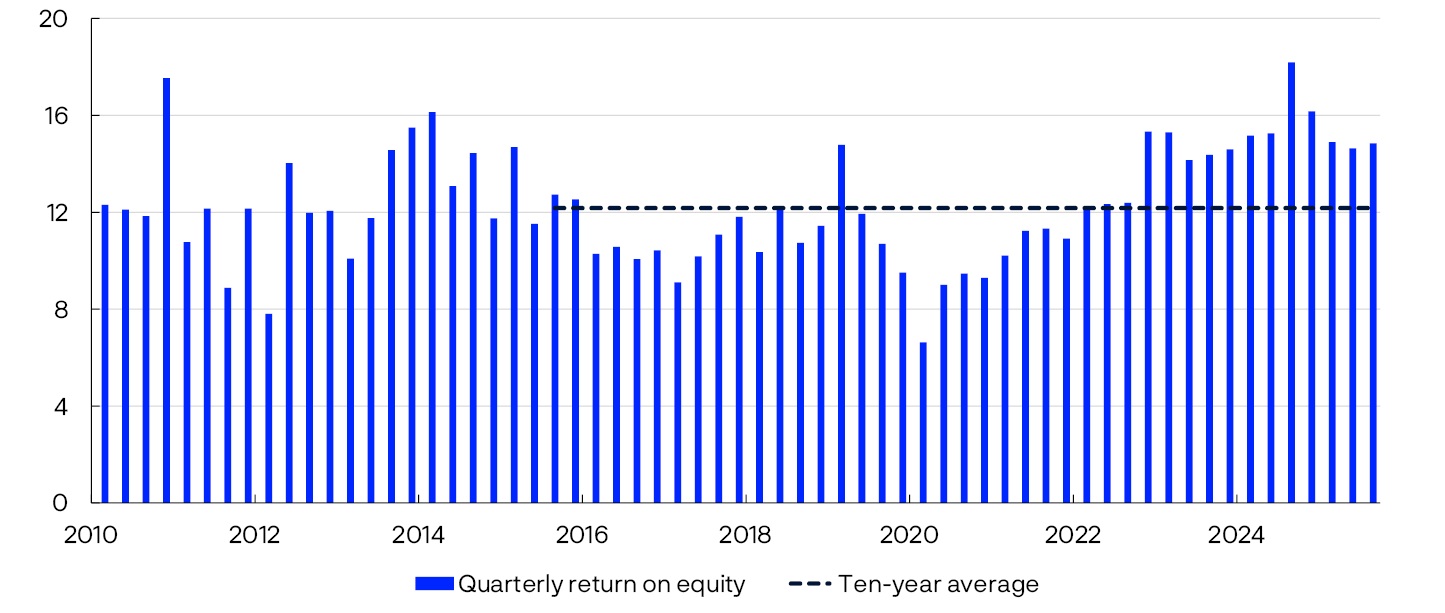

Current earnings are banks’ first line of defence against losses. Return on equity for the large Norwegian banks has been high over the past three years (Chart 1.4). This increase in profitability has been mainly driven by increased net interest income and low losses. Higher net interest income reflects higher interest rate levels in recent years.12 The policy rate forecast from Monetary Policy Report 3/2025 indicates a lower interest rate level in the coming years. Combined with a decline in banks’ interest margins, this will pull down net interest income and thus banks’ profitability.

Return on equity after tax for large banks. Percent

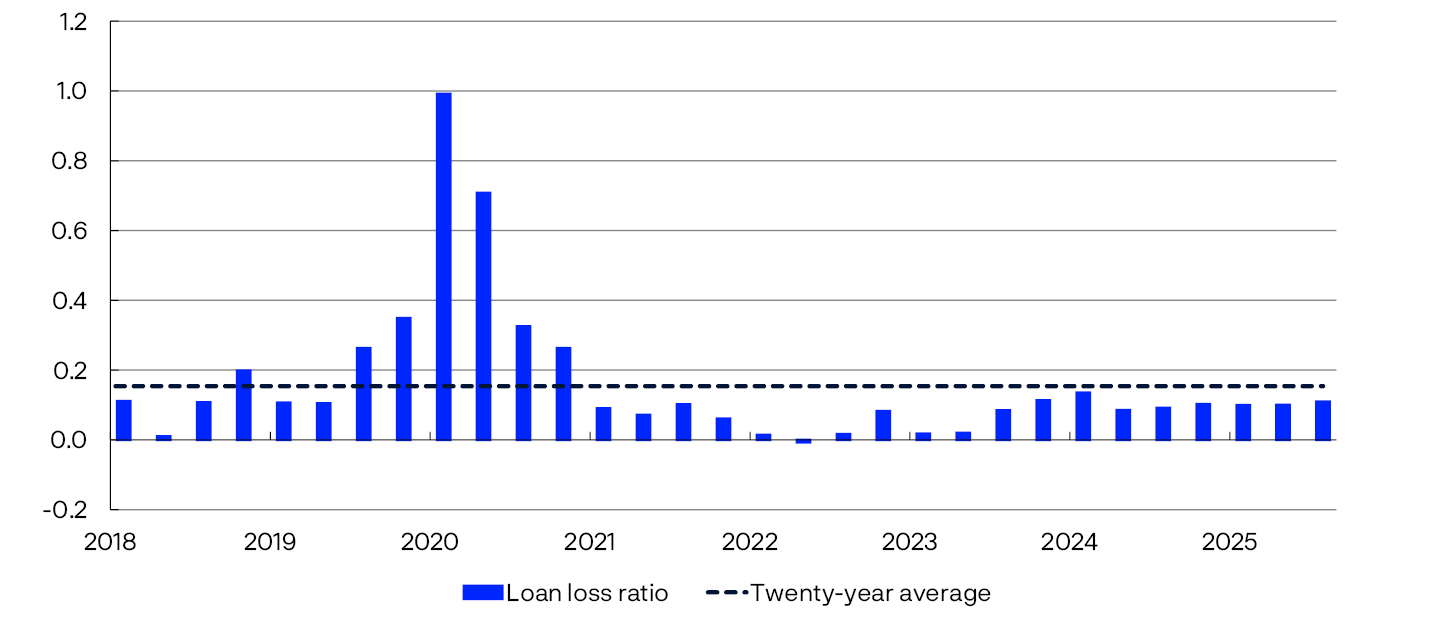

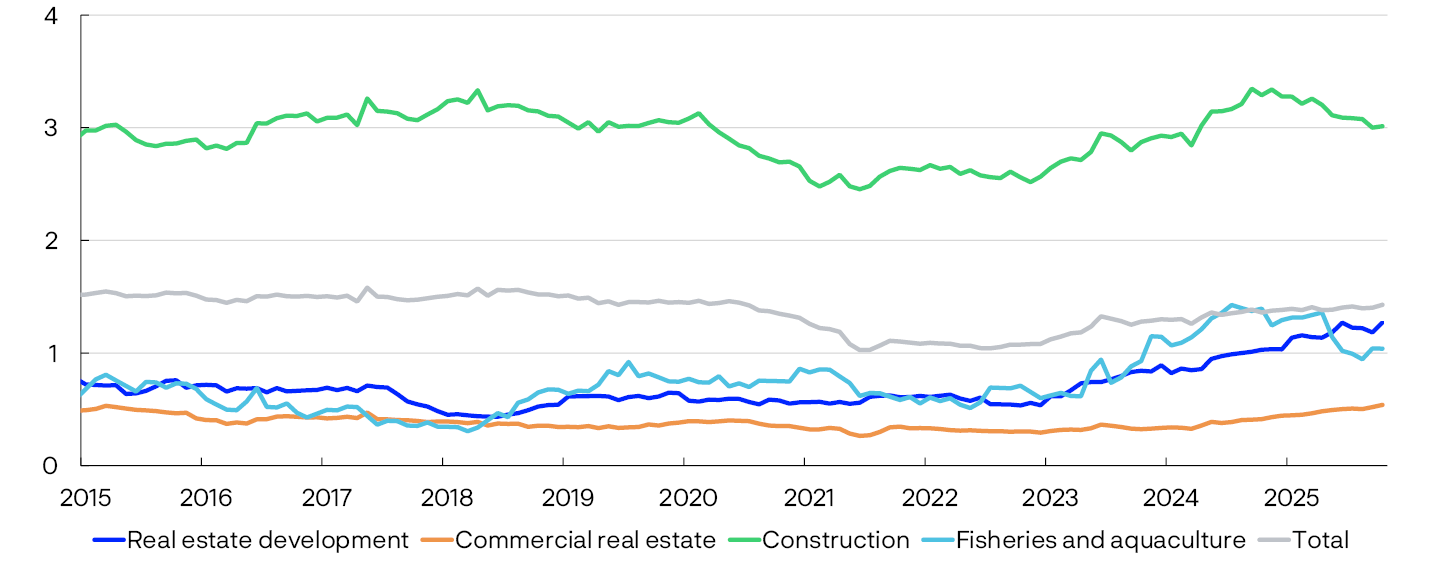

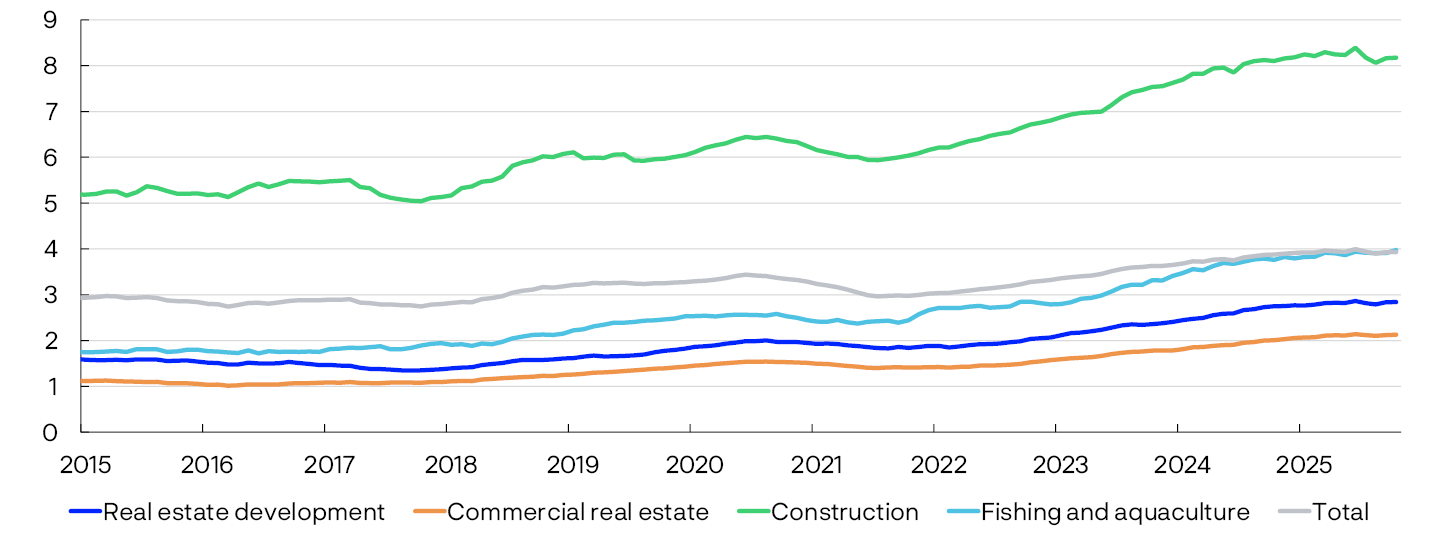

Banks’ total credit losses have remained low and in line with 2024 levels (Chart 1.5).

Loan losses as a percentage of gross loans to customers

Banks’ corporate credit losses have also remained low. Norges Bank expects continued low construction activity to contribute to somewhat higher corporate default rates and credit losses in real estate development over the coming year (for more details, see Section 3). CRE prospects are stable. If employment were to fall markedly and rental income developments in the CRE sector prove markedly weaker than expected, banks could face substantial losses.

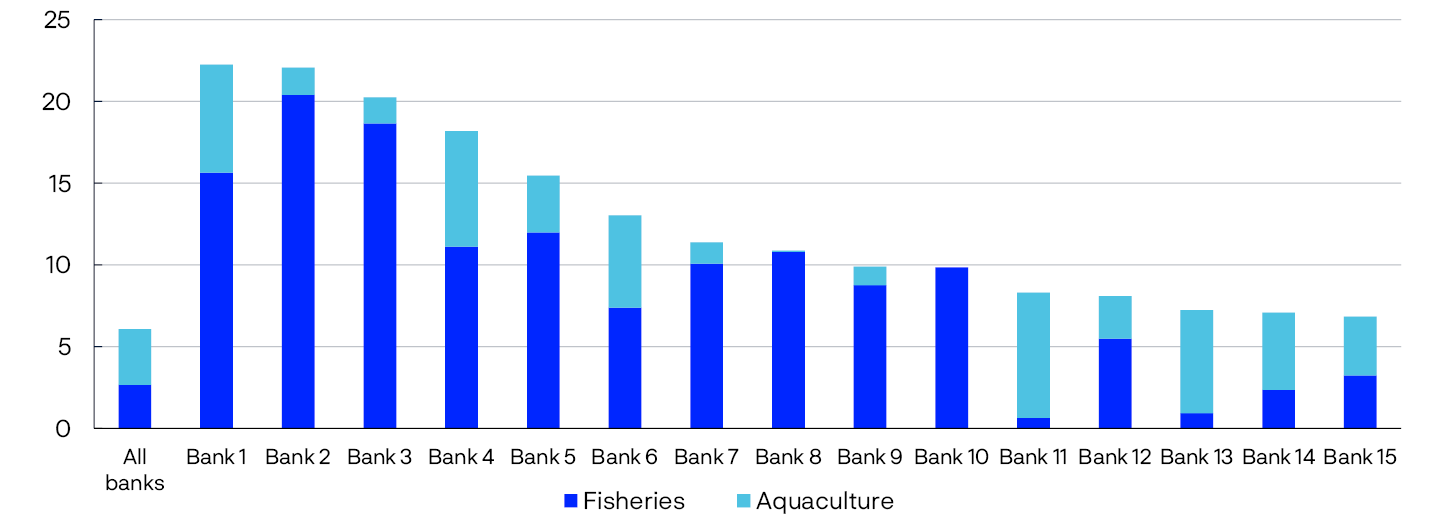

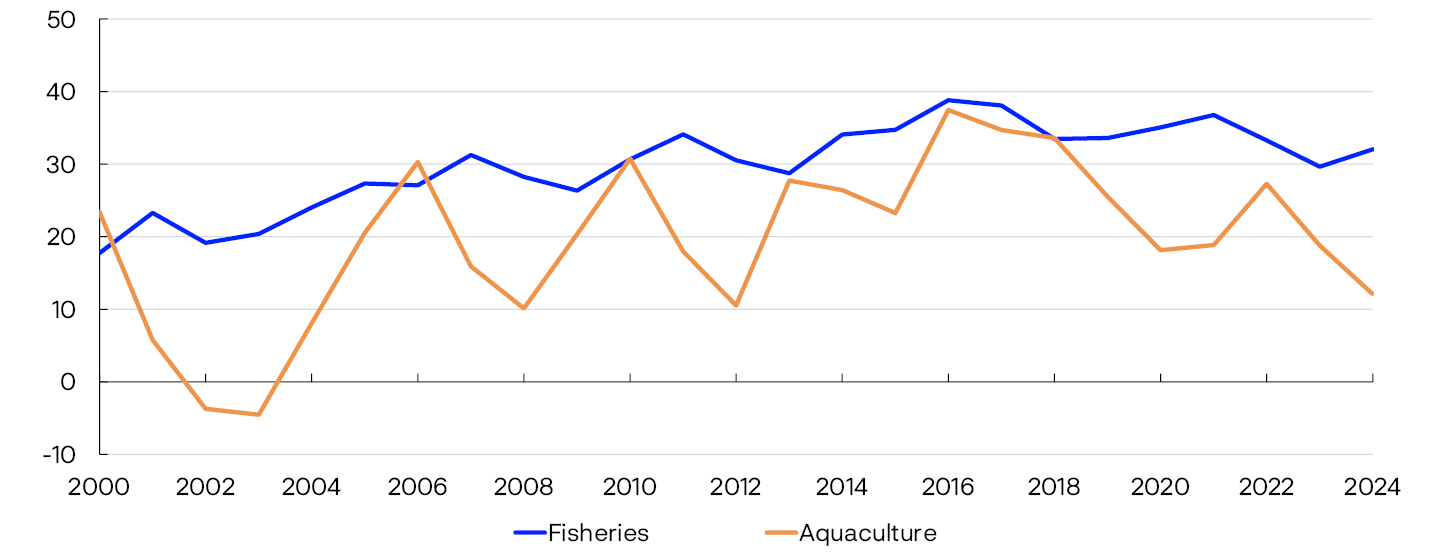

As a whole, Norwegian banks have moderate direct exposure to export-oriented industries, ie those directly impacted by trade restrictions. However, there are regional variations in industry structure, and the exposures of banks with different regional affiliations can vary. Lending to the fisheries and aquaculture sector, which can be affected both directly and indirectly by higher tariffs, accounts for around 6% of total bank corporate lending. See Section 3.2 for a detailed discussion of the impact on the fisheries and aquaculture sector.

Losses on loans to households are low. Looking ahead, higher real household income and lower interest rates are expected to strengthen debt-servicing capacity, and the loss rate on household exposures is expected to remain at a low level.

Banks are solid

Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratios are well above total capital requirements and above banks’ own target ratios. Looking ahead, continued high profitability and low losses are expected to keep banks’ capital adequacy ratios at a high level. The amendments to the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR III), which entered into force on 1 April 2025, mean that banks using the standardised approach (SA) will have lower capital requirements for low-risk exposures. This has increased SA banks’ capital adequacy ratios. So far, IRB banks are less affected by CRR III. The increase of the risk weight floors for IRB banks from 20% to 25% for residential mortgages has, in isolation, somewhat reduced IRB banks’ capital requirements.

The stress test in Financial Stability Report 2025 H1 shows that, on the whole, the largest Norwegian Banks are capable of absorbing large losses while maintaining lending to households and firms, and thereby will not contribute to amplifying an economic downturn.

Households and firms have ample access to credit

Norwegian banks’ financial strength gives them the flexibility to extend loans to creditworthy firms and households, even in the event of market stress and higher losses. In Norges Bank’s lending survey for 2025 Q3, banks reported unchanged credit standards, somewhat stronger household credit demand and slightly weaker corporate credit demand. Banks expect unchanged credit standards and credit demand in Q4. This autumn, bond market activity has been high, and credit premiums for investment-grade firms are close to the average for the past decade. In Norges Bank’s overall assessment, households and firms have ample access to credit.

12 Policy rate hikes increase banks’ interest income more than interest expenses because banks have more interest-bearing assets than interest-bearing liabilities (equity effect). In addition, banks often raise average lending rates more than average deposit rates (interest margin increase).

13 Period: 2010 Q1 – 2025 Q3.

Figures for the six largest Norwegian-owned banking groups. Annualised.

For comparability, the sample has been adjusted retrospectively for major mergers/acquisitions; ie for periods prior to a merger/acquisition, figures for the merged banks have been included.

14 Period: 2018 Q1 – 2025 Q3.

All banks and mortgage companies in Norway. Annualised. Branches and subsidiaries abroad are not included.

Who lends to Norwegian non-financial corporates?

Firms have two main sources of debt financing. They can borrow directly from a financial institution, or they can issue wholesale funding in the form of bonds and short-term papers. Historically, banks have been the most important source of direct lending to firms.

After the 2008–2009 financial crisis, banking regulations were tightened in many countries, leading to a marked rise in direct lending from non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs), particularly in the US. In Europe, growth has been more moderate and most extensive in the UK.

Norwegian non-financial corporates borrow little from Norwegian NBFIs

Domestic credit (C2) and total credit (C3) indicators published by Statistics Norway provide the basis for the mapping of credit to Norwegian non-financial corporates.1 The indicators show firms’ stock of credit from different sources in Norway and abroad.

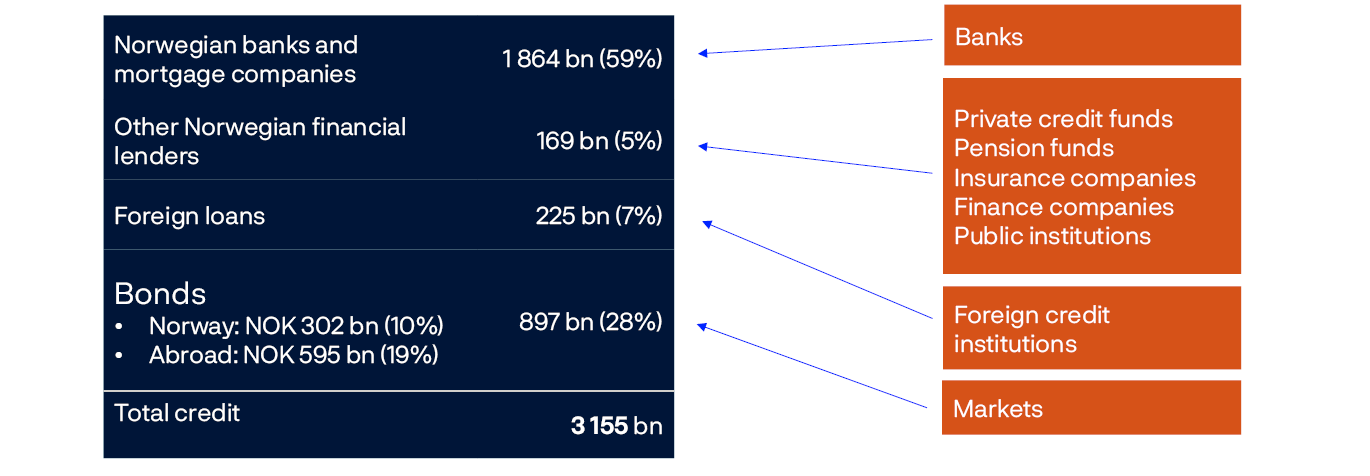

At the end of 2025 Q2, Norwegian firms’ total debt amounted to NOK 3 155bn (Chart 1.A), 59% of which was borrowed from Norwegian banks. Firms also borrow from other Norwegian lenders, such as pension companies and insurance firms, finance companies and public institutions.2 At the end of 2025 Q2, these loans accounted for approximately 5% of total corporate debt. In addition, firms hold some foreign debt, primarily from credit institutions and market-based bond financing.

At the end of 2025 Q2, bonds accounted for approximately 28% of total corporate debt. Around two-thirds of this debt is issued abroad, often in another currency than NOK. Large firms in particular participate in foreign bond markets. Around one-third of bond debt abroad is issued by firms in the petroleum and international shipping sectors.

The distribution of corporate debt has remained relatively stable over time (Chart 1.B, left panel). The share of debt issued by banks has increased somewhat over the past decade. Growth in bond debt issued in Norway was rapid during the pandemic but has slowed in recent years (right panel), largely reflecting lower issuance volumes and a considerable wave of CRE debt maturities. Growth in the issuance of foreign loans and bonds has varied, but increased in total as much as lending by Norwegian banks since 2015 (right panel).

Total credit to non-financial corporates

In contrast to global developments, direct lending from other Norwegian lenders, including NBFIs, has declined somewhat since the peak in 2020 (Chart 1.C). Most of these loans are issued by finance companies that typically provide leasing, factoring and the like. Many of these financial institutions are owned by banks. State lending institutions such as Innovation Norway and Eksportfinans are also important sources of such loans (Chart 1.C).

In billions of NOK

Approximately 1% of corporate credit comes from market participants that are considered NBFIs, ie life and non-life insurance companies and pension funds. Life insurers account for most of the lending.6 Microdata from the Norwegian Tax Administration show that direct lending from NBFIs is largely from a small number of large lenders and to a few borrowers, particularly CRE firms.

In Norway, direct lending from private NBFIs still only accounts for a small share of corporate financing. Amendments to the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD II) may facilitate higher lending activity among private Norwegian NBFIs in the years ahead (see discussion in “Regulatory amendments permit alternative investment funds to engage in lending”).

1 Norges Bank has retrieved data from Statistics Norway for firms’ foreign debt by credit source. Total foreign debt is somewhat lower in these data than total foreign debt in official statistics. Nevertheless, developments are roughly the same.

2 C2 does not include loans from investment funds other than bonds and short-term paper. According to Statistics Norway’s financial accounts, loans from investment funds to non-financial corporates amounted to NOK 54bn in 2025 Q2. However, these financial accounts have limited data for these funds and loans from investment funds to non-financial corporates are used as a balancing item to achieve a better alignment between financial assets and liabilities. This leads to considerable uncertainty regarding actual amounts.

3 Figures as at 30 June 2025.

4 Left panel:

Period: 2015 Q2 – 2025 Q2.

Credit to non-financial corporates from banks and mortgage companies, other Norwegian financial lenders, foreign loans, and bonds issued abroad.

Right panel:

Period: 2015 Q1 – 2025 Q2.

Relative developments in credit to non-financial corporates from banks and mortgage companies, other Norwegian financial lenders, foreign loans, and bonds issued abroad.

5 Period: 2015 Q2 - 2025 Q2

Lending to non-financial corporates that is not from Norwegian banks and mortgage companies, abroad or from bond debt according to Statistics Norway’s data for household and non-financial corporate lending (C2).

6 See footnote 2 on loans from investment funds other than bonds and short-term paper.

Key vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system

The economy is regularly exposed to shocks that affect both the real economy and the financial system. Promoting financial stability means ensuring sufficient financial system resilience to absorb such shocks. The financial system should contribute to stable economic developments by channelling funds and offering savings products, executing payments and distributing risk efficiently. Systemic risk is the risk of disruption to the financial system’s ability to perform these functions.

The level of systemic risk depends on a number of factors. The risk of economic shocks, such as geopolitical tensions, pushes up systemic risk. Financial system vulnerabilities further increase systemic risk. Chart 1.D summarises Norges Bank’s key assessments of Norwegian financial system vulnerabilities.

The high indebtedness of many households is a key vulnerability.

Debt-to-income (DTI) ratios are high compared with other countries. This vulnerability has built up over time as debt levels rose more than household income over an extended period. In the years preceding the pandemic, debt growth slowed and kept more closely in pace with income growth. In recent years, debt growth has been slower than income growth. Debt-to-income ratios have declined broadly across households and most of all for those with the highest DTI ratios. In Norges Bank’s overall assessment, Norwegian household vulnerabilities related to high debt have been somewhat reduced. Vulnerabilities may increase again if looser financial conditions result in rapidly rising house prices and debt. For a more detailed discussion of households’ vulnerabilities, see Section 2.

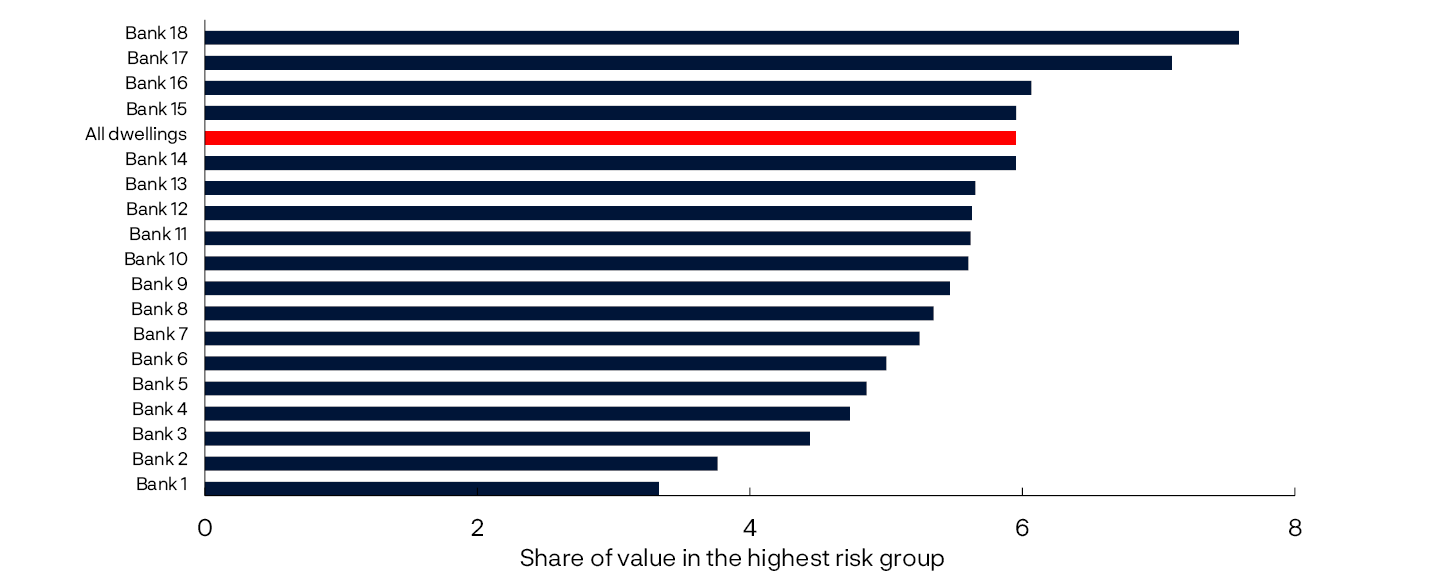

Another key vulnerability is banks’ high CRE exposure. Higher financing costs have reduced CRE profitability, and lower property values have weakened solvency. However, high employment and growth in rental income enable most CRE firms to cover high interest expenses with current earnings. Nevertheless, developments ahead remain uncertain. If interest rates and risk premiums rise markedly or rental income developments prove markedly weaker than envisaged, profitability and property values will weaken. See Section 3 for a more detailed discussion of the CRE sector.

Furthermore, banks in Norway are interconnected through interbank exposures and have common or similar securities in their liquidity reserves (see Financial Stability Report 2025 H1). Covered bonds account for a large part of banks’ liquidity reserves. If a number of banks need liquidity and have to sell such a large quantity of covered bonds that their value falls, the value of covered bond holdings in the liquidity reserves of all other banks will also fall. Cross-holdings of bonds mean that banks fund other banks. If banks are no longer buyers of covered bonds during market stress, this could weaken the possibility of other banks issuing new covered bond funding and could more easily lead to liquidity problems spreading and becoming self-reinforcing.

Digitalisation makes the financial system more efficient but also gives rise to vulnerabilities. Concentration, complexity and interconnectedness may amplify the consequences of a cyberattack that then spreads rapidly and widely across the financial system. If the overall consequences become sufficiently extensive, financial stability could be threatened. With the increased severity of the current threat landscape, consideration must be given to the fact that even well-protected systems can become unavailable. Adequate contingency arrangements are important for managing such serious situations (see Financial Infrastructure Report 2025).

Moreover, banks’ substantial exposures to sectors that are particularly vulnerable to climate transition are a financial system vulnerability. The Norwegian business sector must adapt to climate change and the use of new forms of energy. There is considerable uncertainty about the cost of such a transition, and some firms may see their earnings weaken. If many firms are adversely affected, this may result in higher bank losses. In addition, more extreme weather events can also increase housing-related costs and thereby impact household resilience (see box in Section 2).

However, the financial system can be designed to be more resilient to shocks. In response to financial system vulnerabilities, a number of measures have been introduced to strengthen resilience, including requirements for banks’ solvency, liquidity and credit standards.

Increased interest in stablecoins triggers need for regulation

Stablecoins are cryptoassets that aim to maintain a stable value against a reference asset, most often the US dollar. Issuers maintain the value against the reference asset by securing the coin on traditional financial assets such as securities and bank deposits. Even though stablecoins are currently used as a store of value and for payments within the crypto ecosystem, the range of applications are under development.1

Attributes such as immediate settlement and low transaction costs, particularly for cross-border payments, have boosted global interest in stablecoins. The market value of stablecoins remains low compared with traditional finance and the wider crypto market, but their value has grown rapidly. Their value has increased from USD 3bn in 2019 to over USD 300bn so far in 2025.

A number of major jurisdictions have established special regulatory frameworks for stablecoins. The European Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) Regulation entered into force in Norway under the new Cryptoassets Act on 1 June 2025.2 The legislation applies to cryptoasset issuers and service providers and requires information and documentation for issuances and sales. The MiCA Regulation delegates certain licensing, supervisory and monitoring tasks to the European Central Bank (ECB) and national central banks. On 18 July 2025, the US GENIUS Act was the first federal stablecoin legislation to be adopted.3 GENIUS is similar to MiCA, and a key objective is strengthening the global prominence of the US dollar through the increased use of stablecoins and demand for US government securities. In the UK, stablecoin regulation, with many similarities to MiCA, is also in the pipeline, and the Bank of England has endorsed the possibility of a role for stablecoins in the monetary system.4

Stablecoins are used globally, with many issuers operating in a number of jurisdictions. Stablecoins are designed to be fungible, regardless of where they are issued. Stablecoins issued in multiple jurisdictions (multi-issuer stablecoins) may lead to holders seeking redemption in jurisdictions offering more favourable terms, thereby concentrating vulnerabilities in well-regulated markets if there is a loss of confidence. The ESRB has recommended implementing measures to limit risk related to stablecoins issued in multiple jurisdictions. 5

Stablecoin regulation is still not sufficiently developed to prevent regulatory arbitrage. According to a report from the Financial stability Board (FSB) in October 2025, even though many jurisdictions have established regulatory frameworks for stablecoins, a fair amount of work remains to meet the FSB’s recommendations for regulating global stablecoin arrangements. This highlights the need for further international cooperation to secure financial stability

1 For more details on stablecoins, see: “Stronger interconnections between cryptoassets and traditional finance” in Financial Infrastructure 2025.

2 For more details on Norwegian cryptoasset regulation, see Kryptoeiendelsloven (MiCAR). (Norwegian only).

3 See Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Signs GENIUS Act into Law – The White House.

4 See speech by Sarah Breeden Not just token gestures.

5 See Recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board of 25 September 2025 on third-country multi-issuer stablecoin schemes (ESRB/2025/9).

2.1 Debt-to-income ratios decline further

Many Norwegian households have high debt-to-income (DTI) ratios, and Norges Bank has long considered this high debt to be a key vulnerability in the Norwegian financial system. Historically, household default rates have been low, even in downturns. At the same time, high debt levels, especially when combined with low liquidity, can increase the risk of sharp consumption cutbacks if interest rates rise, household income is reduced or house prices fall markedly. Such cutbacks can affect firms’ earnings and in turn lead to higher corporate credit losses among banks.

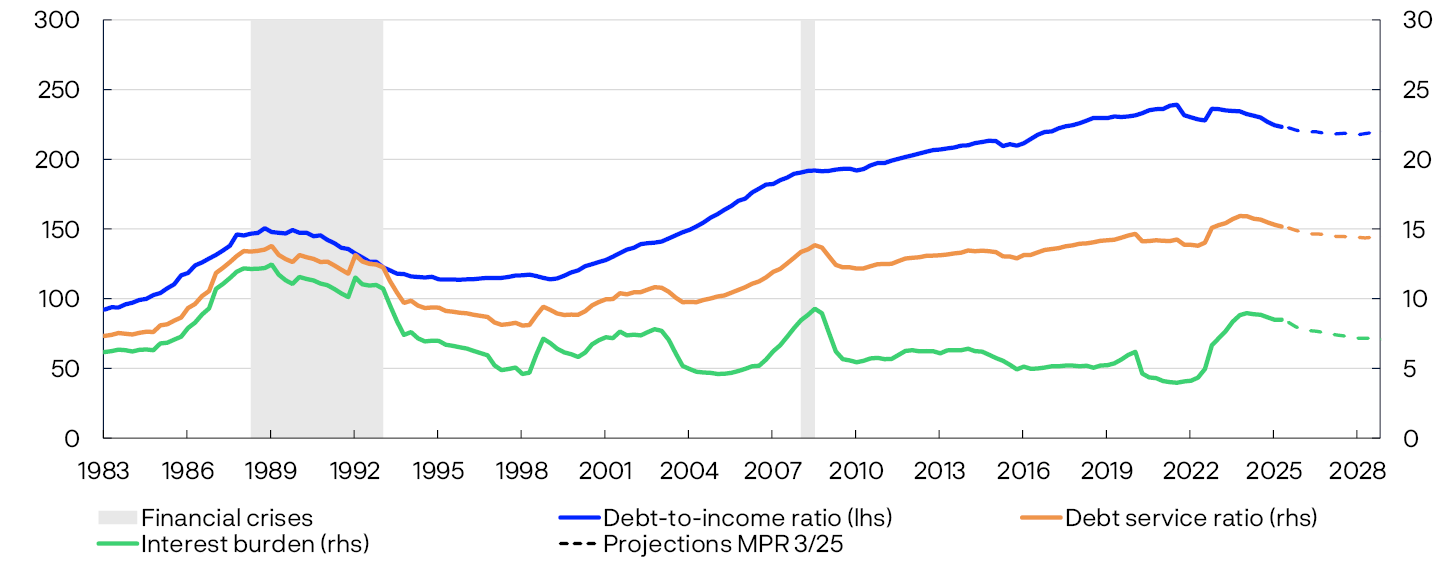

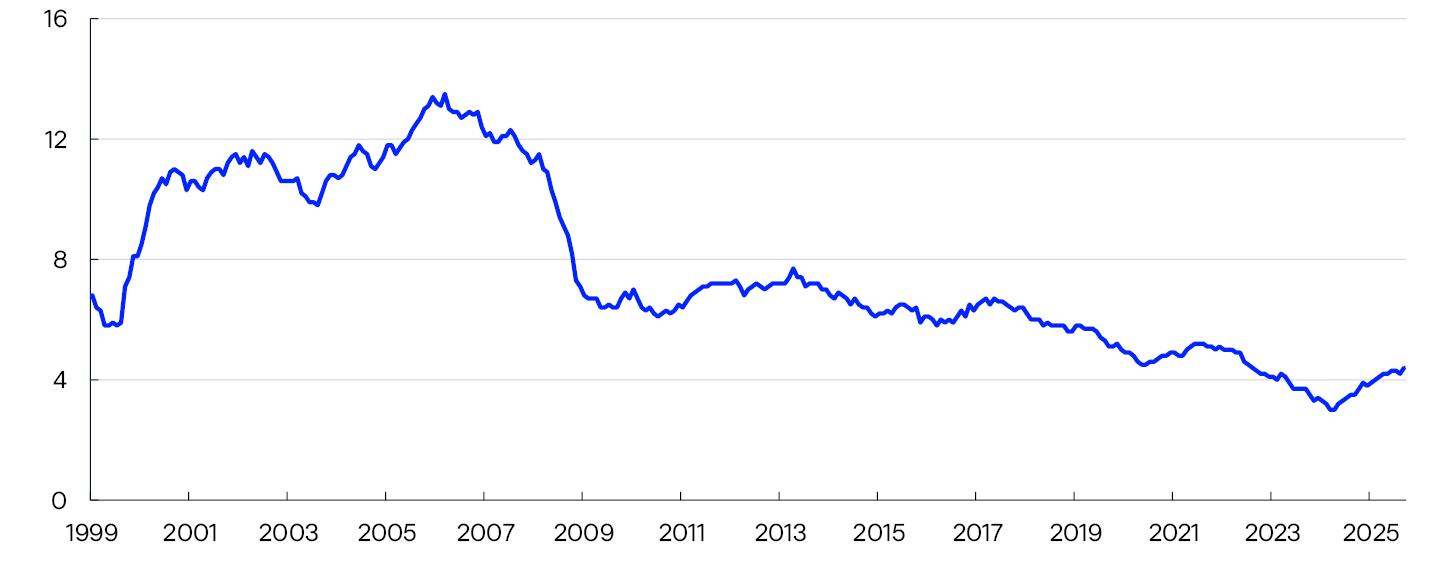

Norwegian household DTI1 ratios rose over many years and are high both historically and compared with other countries (Chart 2.1). Over the past four years, the overall household DTI ratio has levelled off and declined somewhat. Household debt service ratios and the interest burden have declined over the past year, following considerable increases in pace with the rise in interest rates.

According to Finanstilsynet’s (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway) residential mortgage lending survey for 2025, DTI ratios increased somewhat with new mortgages, and a higher share of new mortgages are issued with loan-to-value (LTV) ratios close to 90%. Developments must be viewed in the light of the increase in the Lending Regulations’ maximum LTV ratio requirement at the turn of the year from 85% to 90%. The survey also shows that the share of loans granted to borrowers with low liquidity when interest rate stress tests are considered has declined after increasing for a number of years.2

Looking ahead, DTI ratios are expected to decline slightly further (see Chart 2.1 and Monetary Policy Report 3/2025). A falling DTI ratio means that income rises faster than debt.

Percent

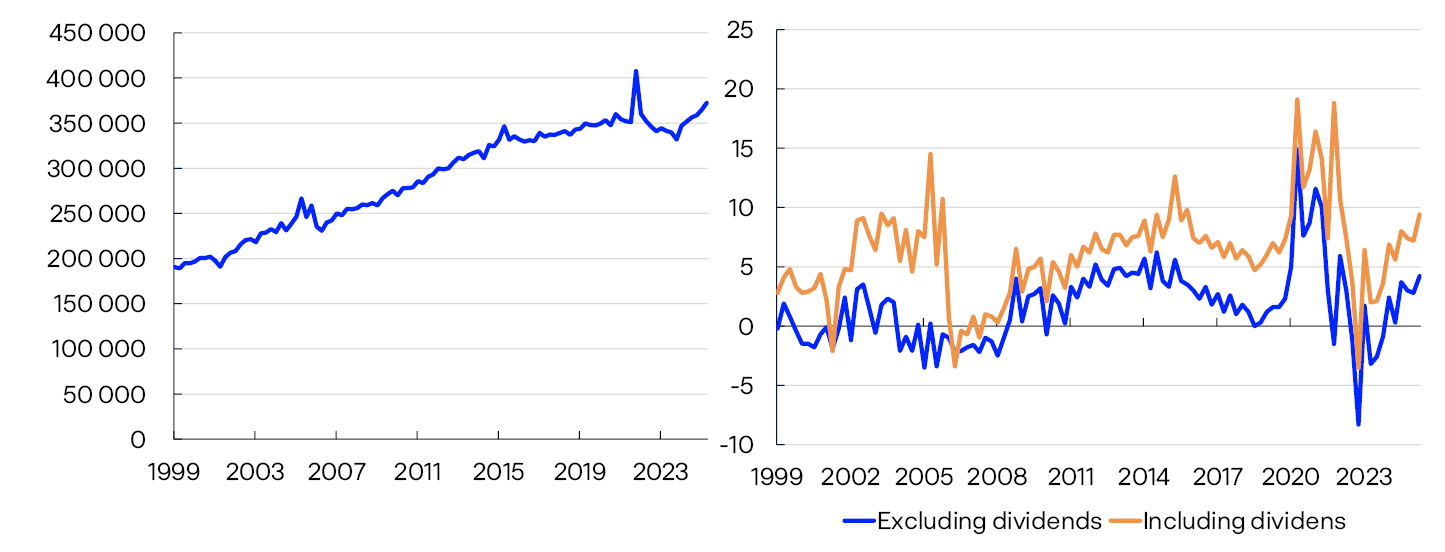

Following a decline in 2022 and 2023, real household disposable income rose rapidly from the start of 2024 (Chart 2.2, left panel). In 2024, the rise in household real disposable income was the sharpest in over a decade. The saving ratio has also moved up again after declining in 2022 (Chart 2.2, right panel). At the same time, household credit growth has picked up somewhat over the past year, with a twelve-month rise of 4.4% in September. This acceleration followed a period of moderating growth, and credit growth remains lower than in the pre-pandemic years (Chart 2.3). According to the banks in Norges Bank’s Survey of Bank Lending, residential mortgage demand increased somewhat in 2025 Q3, while unchanged demand is expected in Q4.

Real disposable income. In millions of 2015 NOK/ Saving ratio. Percent

5Domestic loan debt. Transactions. Twelve-month change. Percent

Household consumer debt increased somewhat in 2022 and 2023, but credit growth has declined over the past two years. At the same time, it has been observed that while credit card usage has increased, interest-bearing credit card debt – ie unsettled credit card debt that accrues interest – has declined since 2022.

The decline in household DTI ratios is broadly based

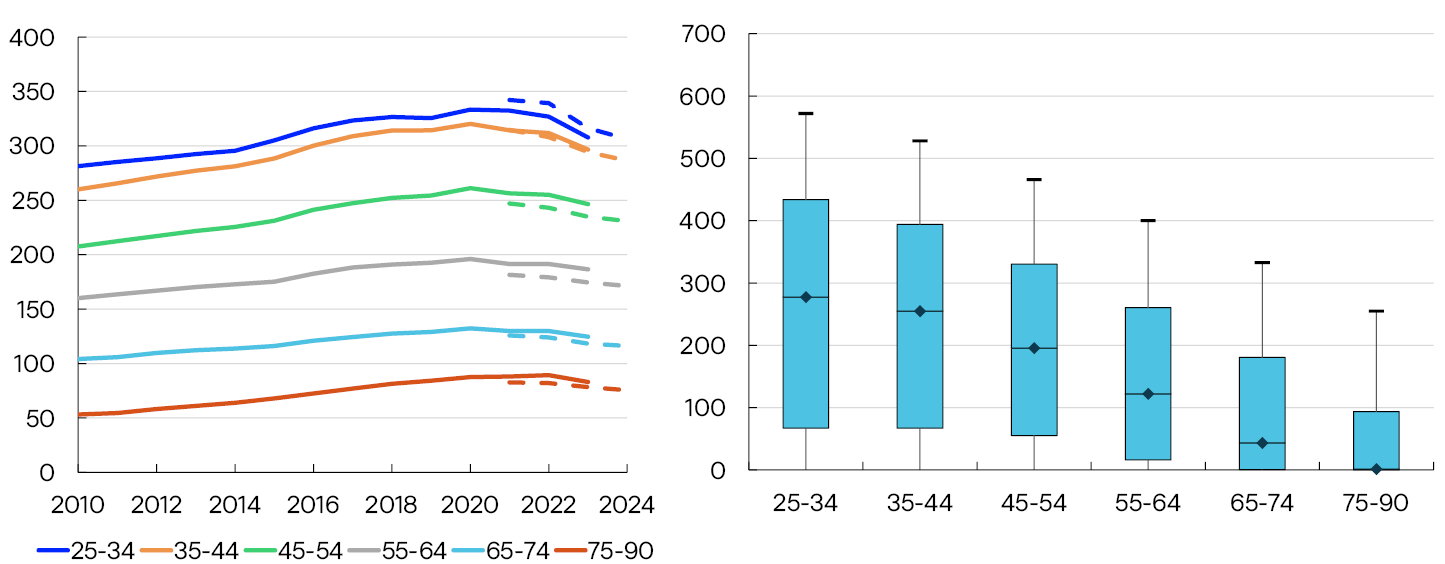

Norwegian households have historically accumulated substantial debt, owing primarily to home purchases early in life. DTI ratios therefore vary considerably between households in different age groups (Chart 2.4, left panel). In recent years, DTI ratios have levelled off and declined in all age groups. Since 2021, the decline has been most pronounced among households under the age of 35, which also have relatively high DTI ratios. At the same time, there are wide differences in DTI ratios within each age group (Chart 2.4, right panel). In the 25–34 age group, 10% of households had DTI ratios higher than close to six times after-tax income in 2024. The median ratio in this age group was approximately three times after-tax income. There is also a large portion of the 35–44 age group with relatively high debt levels. Both the differences within these age groups and the percentage with high debt levels decline markedly with age.

Debt as a share of after-tax income by age group. Percent

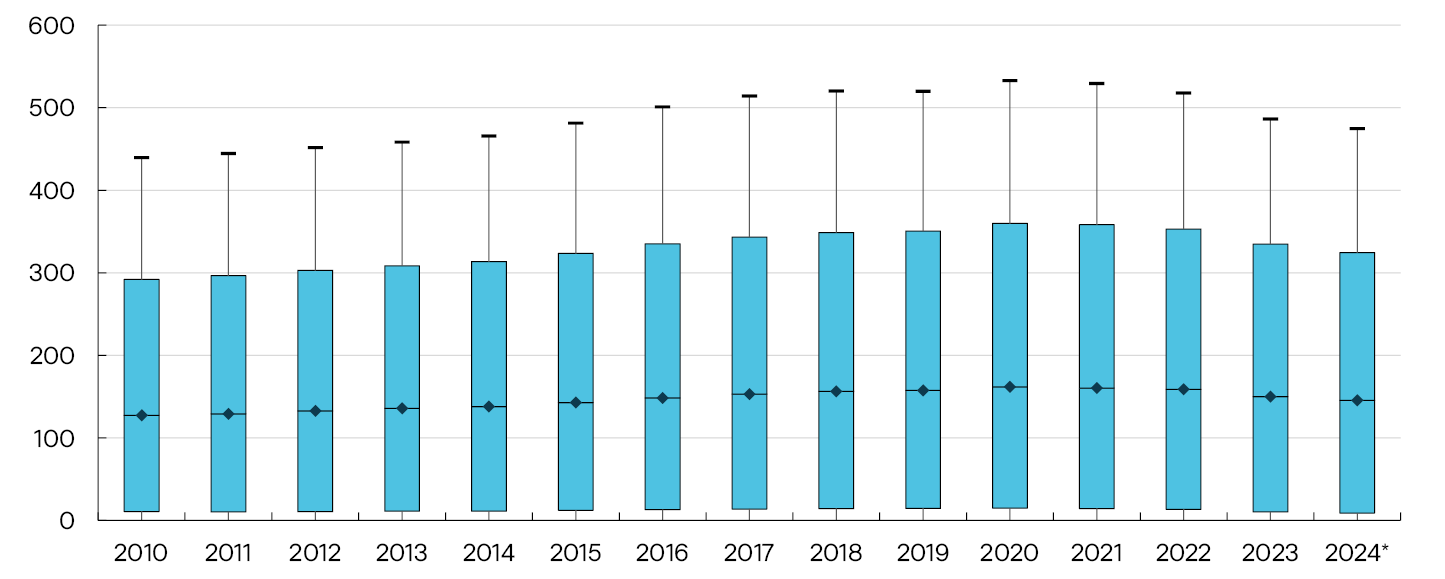

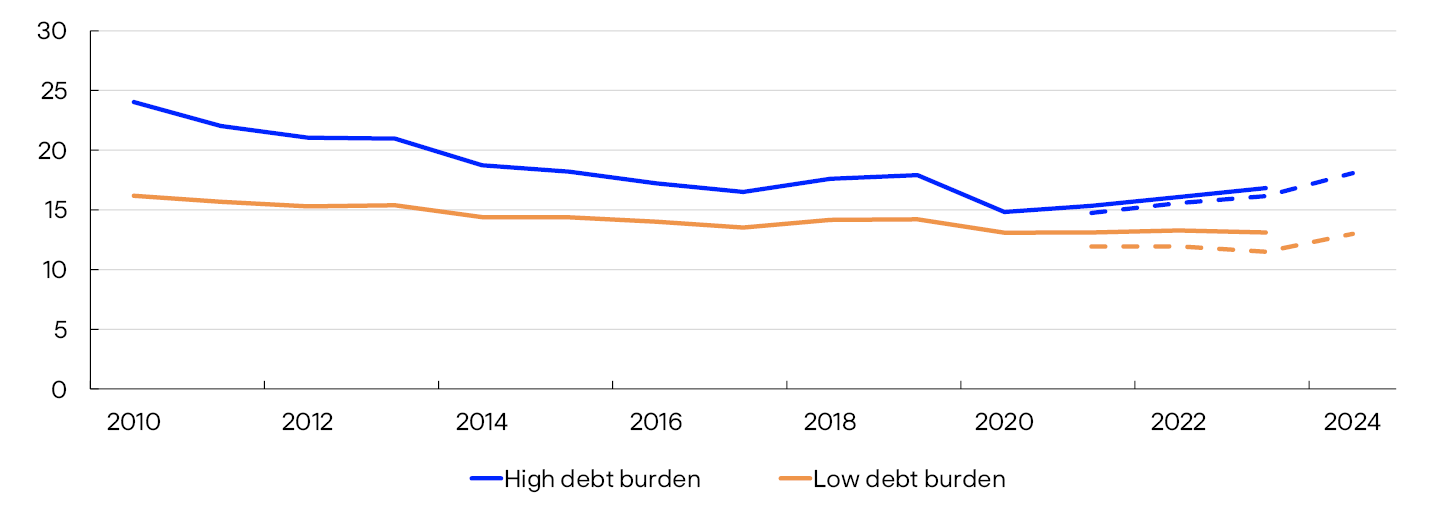

The overall DTI ratio started to decline in 2022, and in 2024, the median DTI ratio was approximately 150% (Chart 2.5). The decline has been most pronounced among households with the highest DTI ratios. This is evident in the chart, which shows that the top of the distribution (90th percentile) has fallen more than the median.

Debt as a share of after-tax income. Percent

Lower household DTI ratios lead to somewhat lower household vulnerability

The high level of household debt is a key financial system vulnerability, particularly as it increases the risk of sharp consumption cutbacks if interest rates rise, household income is reduced or house prices fall markedly. Norges Bank’s assessment is that the broad-based decline in household DTI ratios has reduced this vulnerability somewhat.

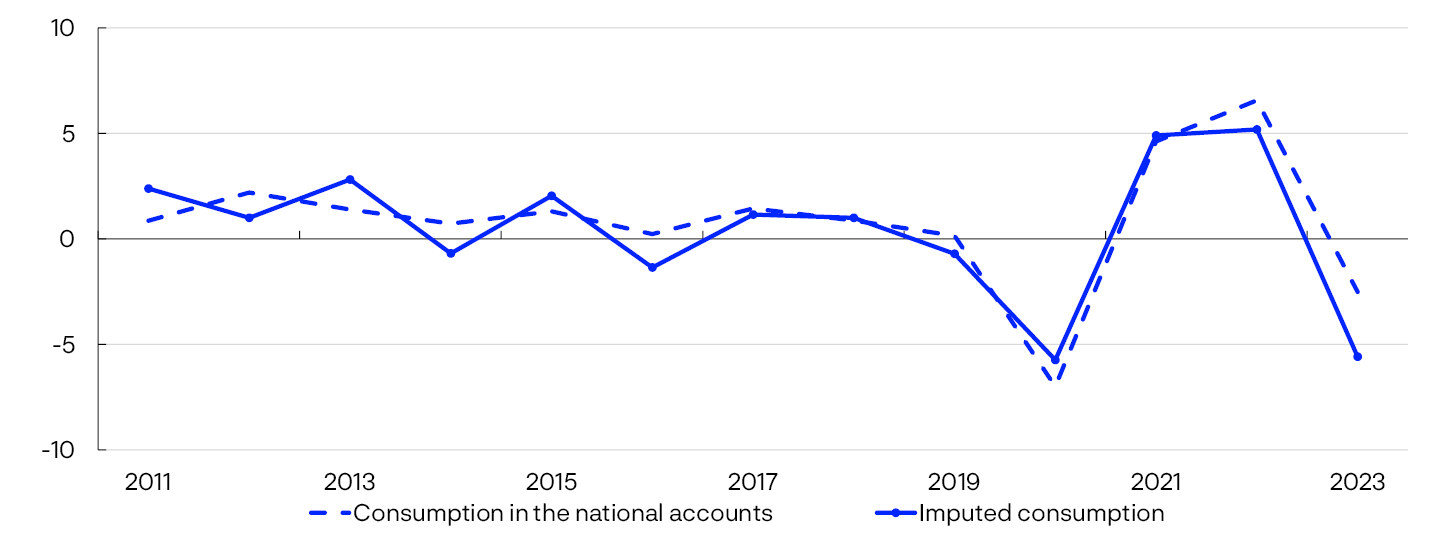

In connection with this Report two analyses have been conducted to shed light on the consumption channel described above (see “Housing-related costs may increase due to more frequent extreme weather events” and “Households with high debt-to-income ratios have reduced consumption the most in response to higher interest rates”).8 The first analysis focuses on how households have adjusted their consumption in the period of higher interest rates and rapid inflation. The analysis shows that highly indebted households have reduced consumption more than those with low DTI ratios. The second analysis focuses on how households adjust consumption in response to a sharp fall in house prices. Again, the analysis shows that households with high DTI ratios reduce their consumption more than those with low ratios.

These findings are in line with existing research.9 The fact that household DTI ratios have now declined, and that the decline has been most pronounced among the households with the highest debt, may therefore dampen consumption cutbacks in response to future interest rate hikes or marked falls in home prices.

1 Debt as a share of disposable income.

2 Finanstilsynet’s definition of low liquidity is that the borrower has a monthly buffer of between NOK 0 and NOK 4000 in accordance with the interest rate stress test.

3 Period: 1983 Q1 – 2028 Q4. Projections from 2025 Q3 for MPR 3/25.

The debt-to-income ratio is debt as a share of disposable income. Disposable income is income after tax and interest expenses.

The debt service ratio is interest expenses and estimated principal payments as a share of after-tax income.

The interest burden is interest expenses as a share of after-tax income.

4 Period: 1999 Q1 – 2025 Q2.

Real disposable income is a measure of households’ purchasing power, adjusted for inflation. It shows the income households are left with after paying interest, taxes, pension contributions, remittances and transfers to non-profit organisations.

The saving ratio is savings as a share of disposable income and is shown here both including and excluding dividends.

5 Period: January 1999 – September 2025.

6 Left panel:

Period: 2010–2024.

Debt-to-income ratio is debt as a share of after-tax income. The chart shows total debt divided by total income. The grouping into age groups is based on the age of the main income earner. Households where the main income earner is self-employed are excluded. Households in the top percentile of net wealth are also excluded. Data from the tax assessment are shown by the dotted lines and are estimates based on household composition from the previous year.

Right panel:

Period: 2024.

The debt-to-income ratio is debt as a share of after-tax income. The grouping into age groups is based on the age of the main income earner. Households where the main income earner is under 25 years, over 90 years, or self-employed are excluded. Households in the top percentile of net wealth are also excluded. The boxplots show the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles (marked, respectively, by the lowest horizontal line along the black vertical line, the bottom of the blue box, the diamond, the top of the blue box, and the top vertical line along the black line). The figures are estimates generated from the tax assessment based on household composition from 2023.

7 Period: 2010–2024.

Debt-to-income ratio is debt as a share of after-tax income. Households where the main income earner is under 25 years old, over 90 years old, or self-employed are excluded. Households in the top percentile of net wealth are also excluded. The boxplots show the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles (marked, respectively, by the lowest horizontal line along the black vertical line, the bottom of the blue box, the diamond, the top of the blue box, and the top vertical line along the black line).

The figures for 2024 are estimates generated from the tax assessment based on household composition from 2023.

8 See Guldbrandsen, M. A. H., S. L. Nilsen and E. S. Njølstad (2025) “Revisiting imputed consumption expenditure during the recent tightening cycle in Norway”, Staff Memo 13/2025. ; Aastveit, K. A., Böjeryd, J., Gulbrandsen M. A. H., Juelsrud, R. E., and Roszbach, K. (2025): “What Do 12 Billion Card Transactions Say About House Prices and Consumption?” Working Paper 15/2025. Norges Bank.

9 See eg Ahn, Galaasen and Mæhlum (2024) “The Cash-Flow Channel of Monetary Policy – Evidence from Billions of Transactions” Working paper 20/2024, Norges Bank, Holm, Paul and Tischbirek (2021) “The Transmission of Monetary Policy under the Microscope”, Journal of Political Economy, 129(10), pp 2861–2904 and Fagereng, Onshuus and Torstensen (2024) “The consumption expenditure response to unemployment: Evidence from Norwegian households”, Journal of Monetary Economics.

2.2 Most households have adequate

debt-servicing capacity

Households’ discretionary income fell further in 2024

The combination of higher interest rates and high inflation in the years after the pandemic has left households with a smaller share of their income after taxes, normal living expenses and interest and principal payments have been paid (Chart 2.6).10 This buffer is referred to as discretionary income. Calculations show that the average discretionary income of Norwegian households amounted to approximately 40% in 2024, down from about 45% in 2021. This decline has mainly been driven by higher interest expenses and food prices. On the other hand, strong nominal wage growth and lower principal payments owing to the repayment of self-amortising mortgages have cushioned the decline in discretionary income. Despite higher expenses, most households are able, by an ample margin, to service debt and cover ordinary living expenses out of current income.11

Expenses as a share of after-tax income. Average. Percent

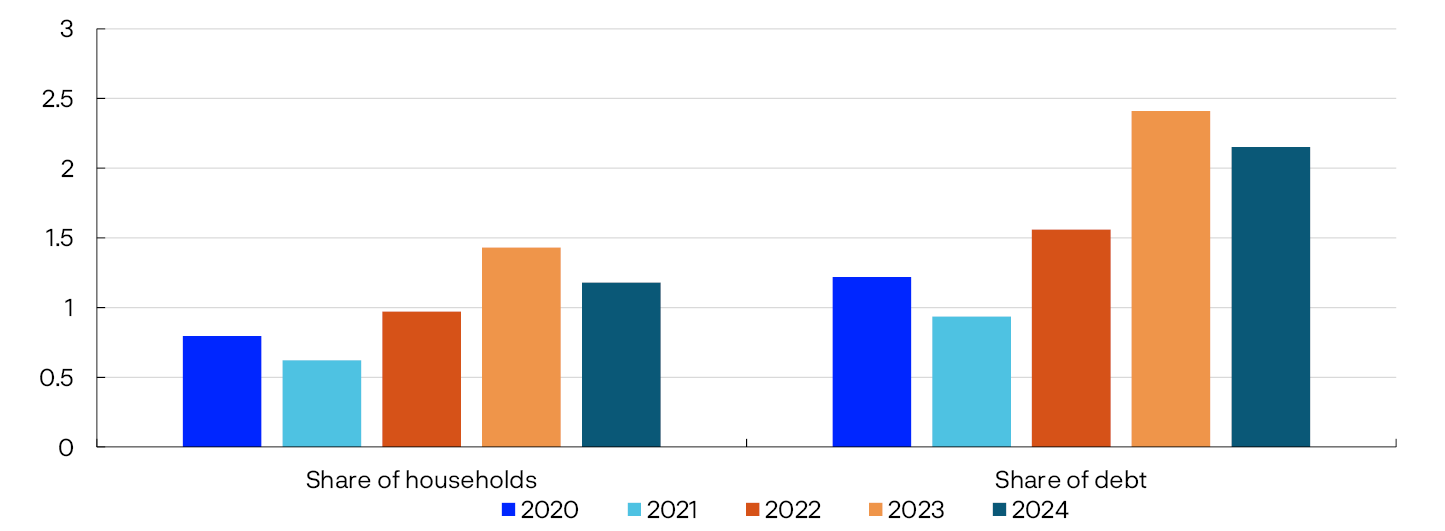

However, an increasing number of households have relatively low levels of discretionary income. The share of households with discretionary income below 40% of their after-tax income has risen steadily since 2021 (Chart 2.7). The share of households with discretionary income of at least 50% of their after-tax income was close to 30% in 2024, broadly the same as in 2023.13

Share of households within different intervals of discretionary income as a share of after-tax income. Percent

Very few households are at risk of defaulting on debt

Approximately 5% of households had negative estimated discretionary income in 2024, slightly lower than in 2023 (Chart 2.7). In order to meet their obligations, these households must either maintain a lower consumption level than assumed in this analysis,15 have unregistered income, draw on accumulated savings or receive transfers from others. In the event of payment problems, they can ask their bank for interest-only periods. Having negative discretionary income does not necessarily mean that a household will default on its debt.

To determine which households are at real risk of debt default, a margin factoring in these possible adjustments is calculated. A negative margin means that a household is not in a position to pay interest unless it reduces consumption to below a normal level.16 Approximately 1.2% of households had negative margins in 2024 (Chart 2.8),17 accounting for approximately 2.2% of overall household debt. The share of households with negative margins is higher than in 2022, but lower than in 2023. Looking at the share of debt held by these households, the same pattern emerges. These calculations are in line with the low residential mortgage default figures.

Share with a negative margin. Percent

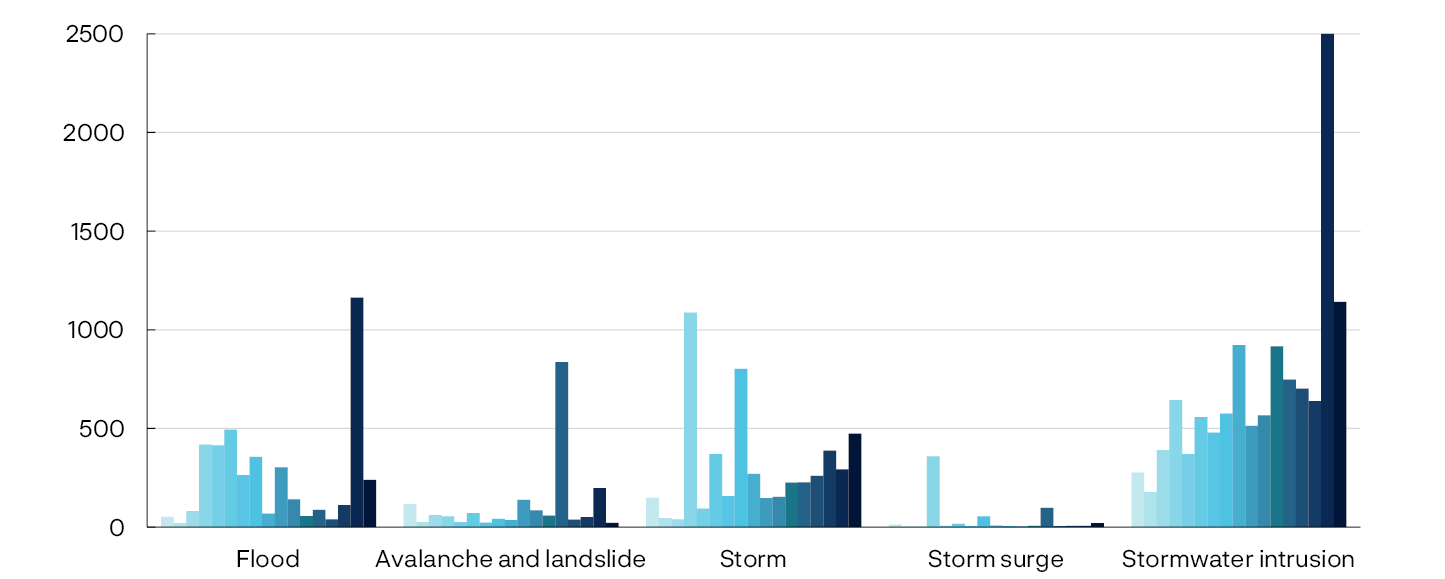

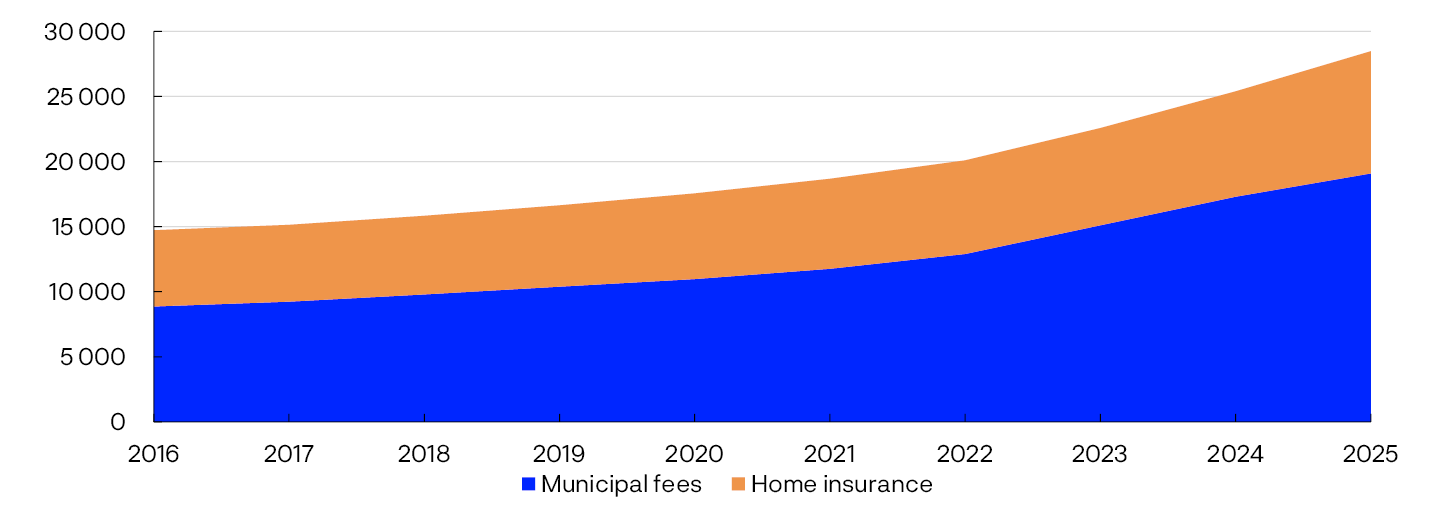

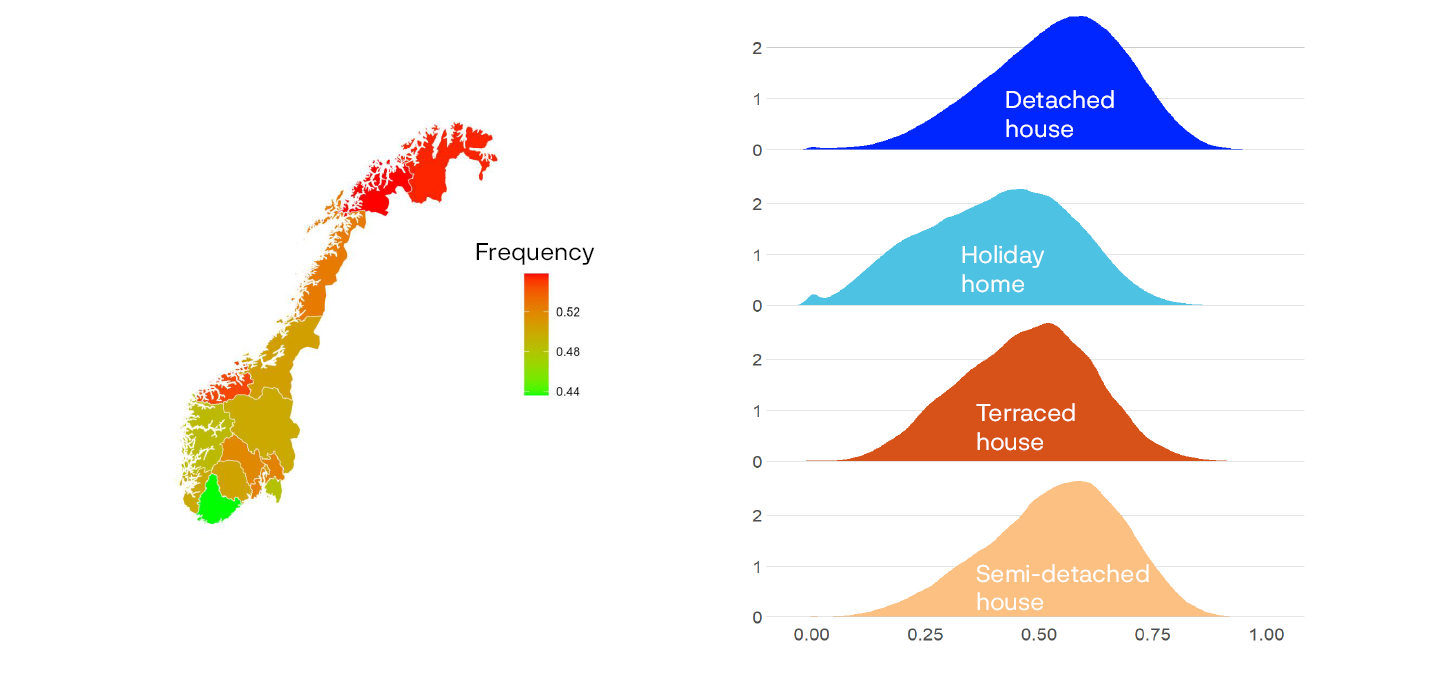

Housing-related costs may increase ahead and reduce discretionary income

Households’ debt-servicing capacity depends to a large extent on the size of their discretionary income, and Norges Bank therefore closely monitors factors that can impact this income. Since the pandemic, higher interest and food expenses in particular have reduced discretionary income. One factor that could potentially reduce discretionary income ahead is higher housing-related costs given higher physical climate risk. The rise in home insurance premiums has outpaced consumer price inflation in recent years and was particularly sharp between 2023 and 2024 following the extreme weather event “Hans”. Municipal fees have also increased, partly due to changes in weather conditions resulting in wear and tear on public infrastructure. If changes in weather conditions continue to lead to higher public fees and insurance premiums, a rise in housing-related costs can be expected (see “Lower housing affordability in urban areas: how do first-time buyers respond?”). When calculating discretionary income, housing-related costs are found to amount to a relatively modest share of household after-tax income. At the same time, such costs have increased substantially in other countries. Natural disaster insurance and preventive measures may help dampen the risk of similar developments in Norway and thereby limit the reduction in household discretionary income.

10 Note that households are limited to owner-occupiers, which means that some of the households with the smallest margins are excluded.

11 Finanstilsynet’s residential mortgage lending survey for 2025 shows that the share of loans granted to borrowers with low liquidity when interest rate stress tests are considered has declined after increasing for a number of years.

12 Period: 2020–2024.

The sample only includes households that own their own home.

Self-employed persons and homeowners where the main income earner is under 20 or over 90 years old are excluded. Those with the top 1% highest and lowest incomes, and those with the top 1% highest financial assets, are also excluded.

Discretionary income is the money remaining after households pay taxes, cover debt expenses and normal living expenses. Debt expenses include interest payments and also, if the LTV ratio is over 60%, principal payments.

Normal living expenses cover food, other essential consumption and housing expenses. Food and other essential consumption are based on household size and SIFO’s reference budget. Housing expenses include municipal fees, property tax and insurance. In addition, electricity expenses are estimated based on the home’s size, type, and electricity zone.

13 Owing to an error in underlying data used in Financial Stability Report 2024 H2, Chart 2.5 was misleading. For example, the share of households with discretionary income below 30% of after-tax income should have been around 40% rather than 7%, and the share with more than 50% of their income as discretionary income should have been around 25% instead of 60%.

14 Period: 2020–2024.

The sample only includes households that own their own home.

Self-employed persons and homeowners where the main income earner is under 20 or over 90 years old are excluded. Those with the top 1% highest and lowest incomes, and those with the 1% highest financial wealth, are also excluded.

Discretionary income is the money remaining after households pay taxes, cover debt expenses and normal living expenses. Debt expenses include interest payments and, if the loan-to-value ratio is over 60%, also principal payments.

Normal living expenses cover food, other essential consumption and housing cushioned. Food and other essential consumption are based on household size and SIFO’s reference budget. Housing cushioned include municipal fees, property tax, and insurance. In addition, electricity expenses are estimated based on the home’s size, type and electricity zone.

15 The Consumption Research Norway (SIFO) reference budget is included as a basis. The budget shows the cost of maintaining an acceptable level of consumption – a level that is generally considered reasonable – for the household in question. Nevertheless, this is not a minimum budget, and certain households may therefore consume less when finances are tight.

16 When calculating the margin, it is assumed that banks will grant interest-only periods to households facing payment difficulties if the LTV ratio is below 60%. Borrowers can also draw on some of their accumulated savings to cover ordinary living expenses and interest payments. This means drawing on deposits and funds, as well as the possibility of increasing the LTV ratio if it is below 60% (see Lindquist, Solheim og Vatne (2022): “Norwegian homeowners’ debt-servicing capacity is adequate”, Staff Memo 8/2022, Norges Bank.

17 This corresponds to approximately 20 000 households.

18 Period: 2020–2024.

The sample only includes households that own their own home.

Self-employed persons and homeowners where the main income earner is under 20 or over 90 years old are excluded. Those with the top 1% highest and lowest incomes and those with the top 1% highest financial wealth, are also excluded.

A negative margin indicates when the household is no longer able to service its debt without having to reduce consumption below a normal level.

When calculating the margin, households with payment difficulties are assumed to be granted an interest-only period by the bank if the loan-to-value ratio is below 60%. The borrower may also use some of their savings to cover normal expenses and interest payments. This includes drawing on deposits and funds, as well as the possibility to increase the loan-to-value ratio if the loan is less than 60% of the value of the home.

2.3 Households’ liquid buffers have increased over a long period, but have been reduced somewhat in recent years

Bank deposits are the most common form of savings for households

Bank deposits are the most liquid of households’ accumulated savings and the dominant form of financial wealth for most households (Chart 2.9).19 Bank deposits account for more than 90% of the financial wealth of half of Norwegian households, while just over a third of households only have bank deposits. At the same time, financial wealth has become slightly more diversified in recent years as a result of more households saving in funds and other financial assets. Some of these investments, such as broad-based index funds, are liquid and relatively simple to sell to improve household liquidity.

Bank deposits’ share of financial wealth. Percent

Households’ liquid buffers have been somewhat reduced as a share of income in recent years

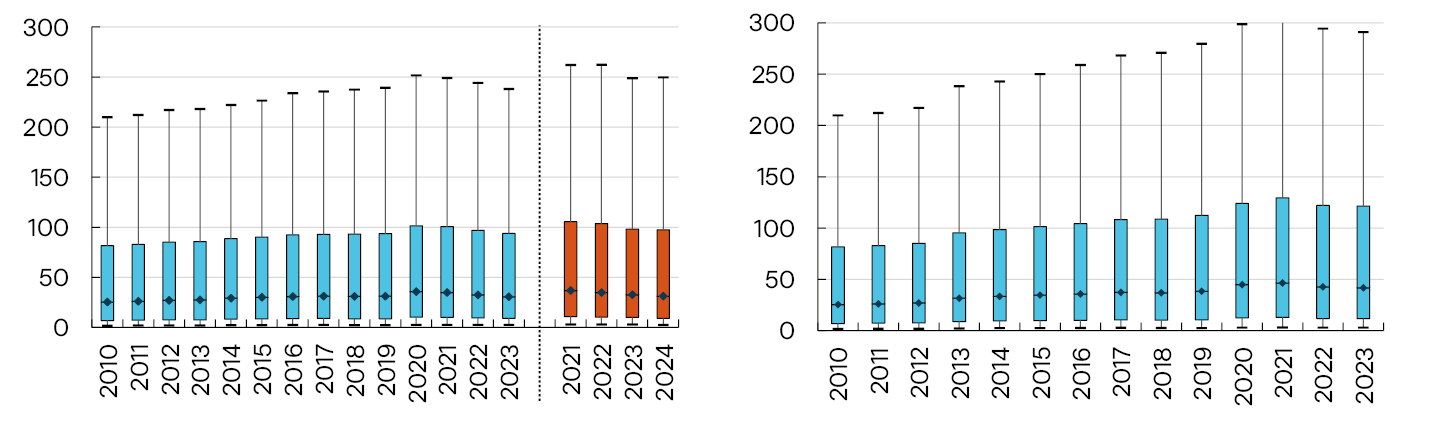

Liquid buffers improve households’ ability to handle unforeseen expenses or a loss of income. After having risen for several years and surged during the pandemic, bank deposits as a share of after-tax income declined in pace with higher interest rates and high inflation (Chart 2.10, left panel). In 2023, the share returned to around pre-pandemic levels. For the median household in 2023, deposits amounted to slightly more than 30% of annual after-tax income. Preliminary data from the Norwegian Tax Administration and aggregated figures from Statistics Norway’s financial sector accounts indicate that the share has fallen slightly further in 2024 and 2025.

Bank deposits’ share of after-tax income. Percent / Liquid assets’ share of after-tax income. Percent

If fund units and equity savings account balances are included in liquid buffers, the level rises substantially (Chart 2.10, right panel).22 With this broader measure, buffers increased further in 2021, although bank deposits as a share of income declined. This means that the increase in holdings invested in equity savings accounts and fund units exceeded the fall in bank deposits. In 2023, the median household held total liquid buffers equal to just above 40% of annual after-tax income. This is higher than in the year preceding the pandemic and also reflects the changed composition of households’ financial portfolios in recent years. Statistics Norway’s financial sector accounts show that the aggregated household fund unit holdings have risen considerably faster than disposable income through 2024 and so far in 2025.

At the same time, some households have little or no liquid buffers in the form of bank deposits. After falling for a long time, the share of households in this category has increased slightly since the pandemic, in particular for households with high debt (Chart 2.11), and in 2024, this share had returned to around pre-pandemic levels.

Share of households with bank deposits less than half a month’s after-tax income. Percent

For some households, such a small buffer means that they have little ability to meet unforeseen expenses or manage a loss of income. At the same time, there are also households that have adapted by having small bank deposits for other reasons than little discretionary income. Households can choose to keep their financial savings in assets other than bank deposits or they may have home equity lines of credit that can easily supply liquidity by increasing household borrowing to meet unforeseen events.

Many homeowners can improve their liquidity by borrowing against home equity

In addition to drawing on savings, many homeowners can, as mentioned above, increase liquidity by taking on new debt against home equity. To shed light on this channel, households are assumed to have easy access to loans if their LTV ratio is below 60%.24

By this definition, approximately two out of three homeowners could increase their borrowing in 2023 (Chart 2.12, left panel).25 Among those homeowners, around half had a potential liquidity buffer equal to more than double their after-tax income (Chart 2.12, right panel). This share has increased over time, measured relative to after-tax income, but declined somewhat through 2023.

Share of homeowners with available collateral (LTV below 60%) by age group. Percent / Available collateral in the home as a share of after-tax income (LTV below 60%). Percent

19 The data do not continue after 2023 as the figures from the Norwegian Tax Administration, which include 2024, have not been processed in the same way as the income and wealth statistics for households from Statistics Norway.

20 Period: 2010–2023.

Households where the main income earner is under 25, over 90, or self-employed are excluded. Households in the top percentile of net wealth are also excluded. The boxplots show the 10th, 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles (marked, respectively, by the lowest horizontal line along the black vertical line, the bottom of the blue box, the diamond, the top of the blue box).

21 Period: 2010–2024.

Households where the main income earner is under 25, over 90, or self-employed are excluded. Households in the top percentile of net wealth are also excluded. The boxplots show the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles (marked, respectively, by the lowest horizontal line along the black vertical line, the bottom of the blue box, the diamond, the top of the blue box, and the top vertical line along the black line).

The orange bars are estimates generated from tax assessments based on household composition from the previous year.

Liquid assets are defined as bank deposits, equity savings accounts and funds.

22 The data do not continue after 2023 as the figures from the Norwegian Tax Administration, which include 2024, have not been processed in the same way as the income and wealth statistics for households from Statistics Norway.

23 Period: 2010–2024.

Debt burden is debt as a share of after-tax income. Low debt burden is a debt burden below 300%. High debt burden is a debt burden above 300%. Households where the main income earner is under 25, over 90, or self-employed are excluded. Households in the top percentile of net wealth are also excluded. The dashed lines show figures from tax assessments and are estimates based on household composition from the previous year.

24 In such a situation, most households can relatively quickly and easily increase their mortgage up to an LTV ratio of 60%. Many can borrow more, but this is a limit that makes borrowing swiftly and easily available, making it a better measure of household ability to improve current liquidity. The Lending Regulations also have a maximum LTV ratio of 60% for home equity lines of credit.

25 The data do not continue after 2023 as the figures from the Norwegian Tax Administration, which include 2024, have not been processed in the same way as the income and wealth statistics for households from Statistics Norway.

26 Period: 2010–2023.

Available collateral is defined as households with a loan-to-value ratio below 60%. Loan-to-value ratio is defined as total debt minus student debt and unsecured debt as a share of the value of the primary residence. Households where the main income earner is under 25, over 90, or self-employed are excluded. Households in the top percentile of net wealth are also excluded. The boxplots show the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles (marked by, respectively, the lowest horizontal line along the black vertical line, the bottom of the blue box, the diamond, the top of the blue box, and the top vertical line along the black line).

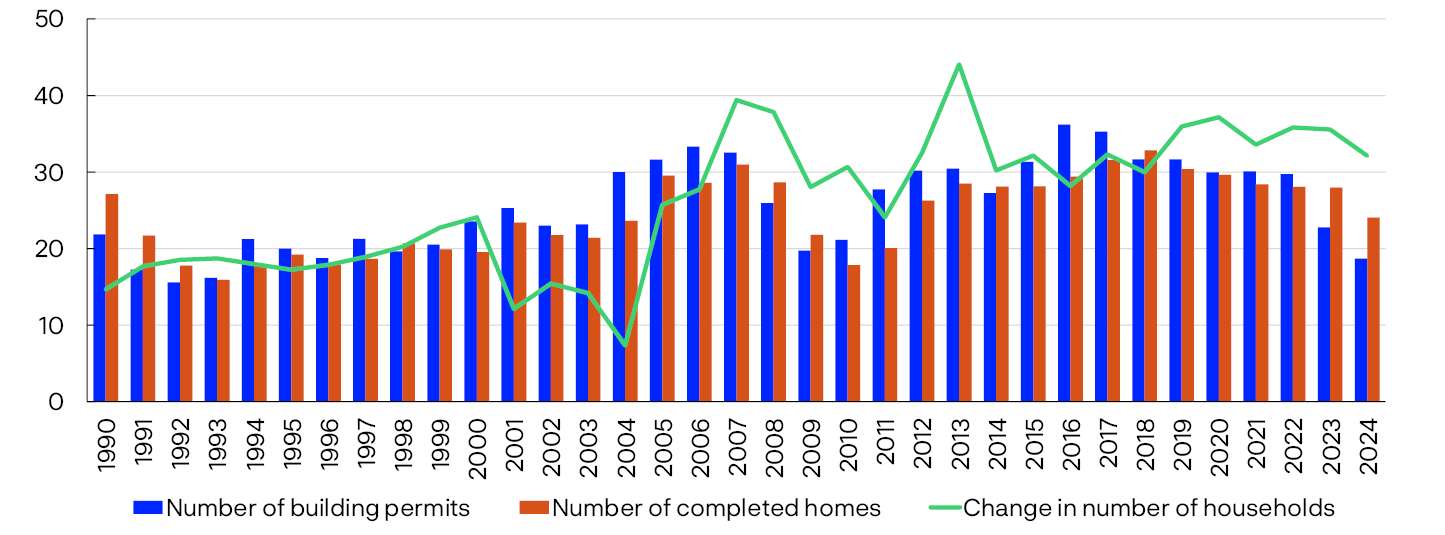

2.4 Low residential construction and high demand contribute to higher house prices

The housing market is key to the assessment of financial stability, partly due to the interplay between house prices and debt.27 Homes are important assets for households and a key factor why they take on large debts. House prices have periodically risen considerably faster than household income, for example before the banking crisis in the early 1990s, before the financial crisis in 2008 and during the pandemic. This increased household sector vulnerability as household DTI ratios increased at the same time (Chart 2.1). In recent years, house prices as a share of disposable income have levelled off.

In 2024, prices in the secondary housing market increased by 3%. In the first half of 2025, house prices increased considerably. Regulatory easing of equity requirements for house purchases and expectations of lower interest rates may have contributed to the increase. However, house price inflation has since been lower. Looking ahead, house prices are expected to increase somewhat faster than household income due to lower interest rates and a low supply of new homes (see Monetary Policy Report 3/2025).

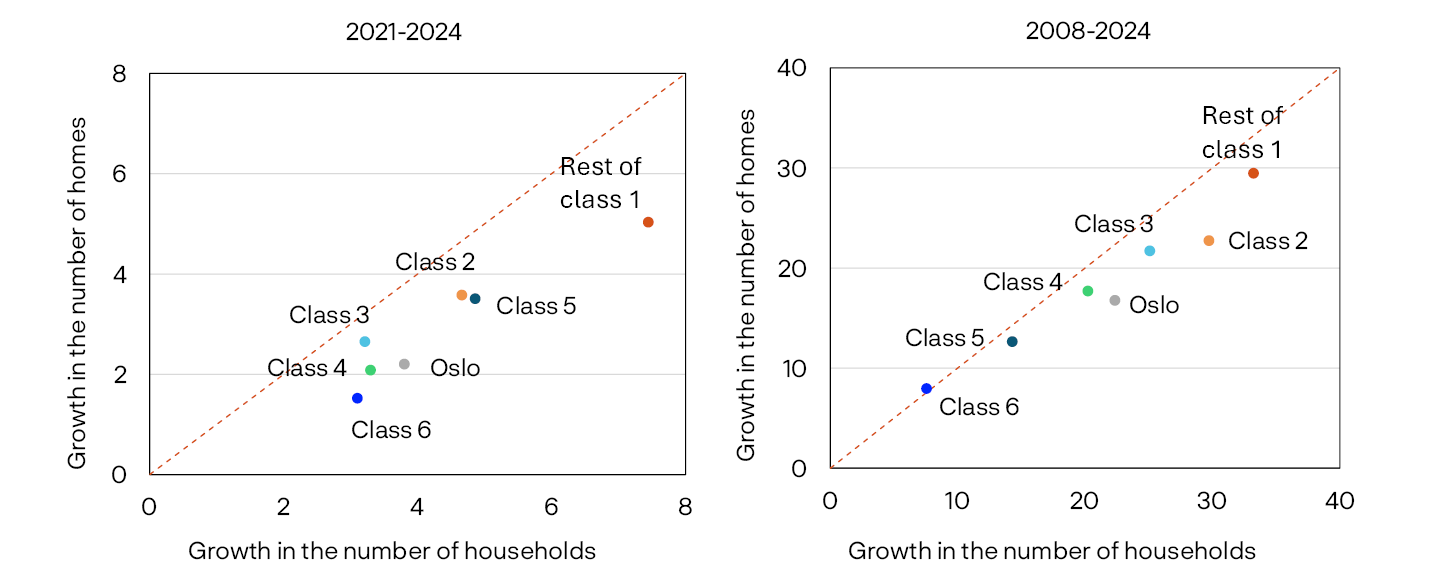

Lower housing affordability for households

When house prices increase faster than income over time, this may lead to fewer households gaining the opportunity to buy their own home. Such developments may influence households’ total borrowing and the distribution of risk between households, banks and other market participants. For banks, fewer new homeowners may dampen lending growth and reduce default risk if the most vulnerable households postpone buying a home to save more equity and benefit from higher income.

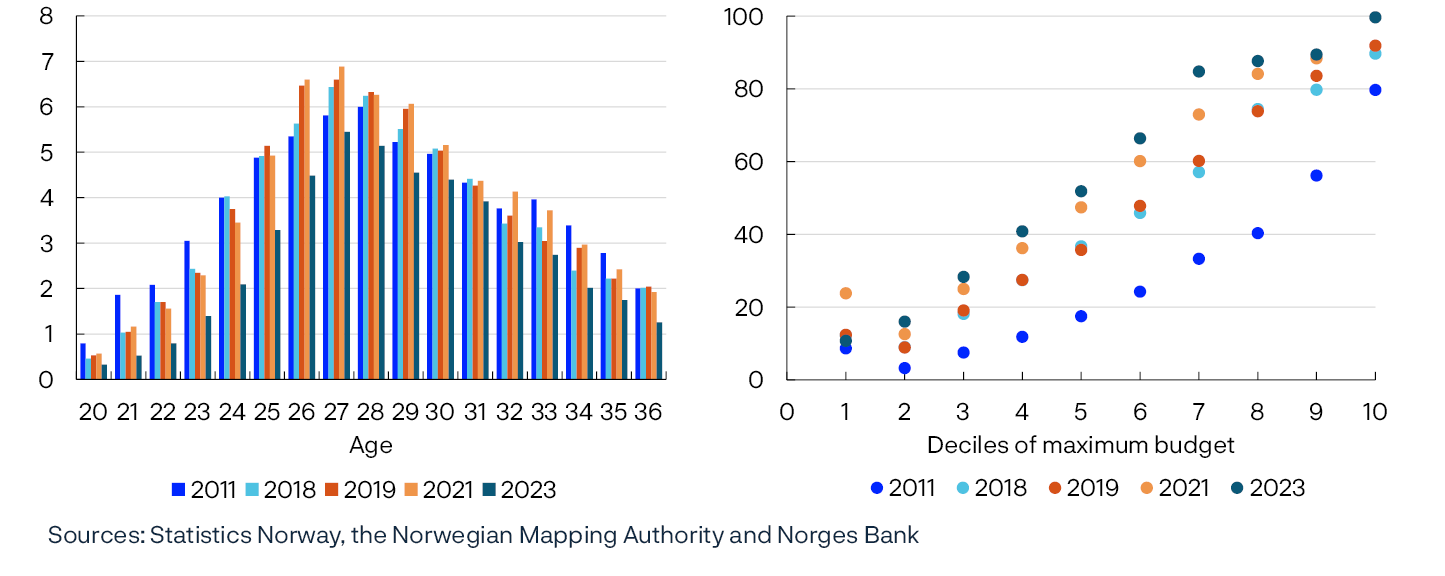

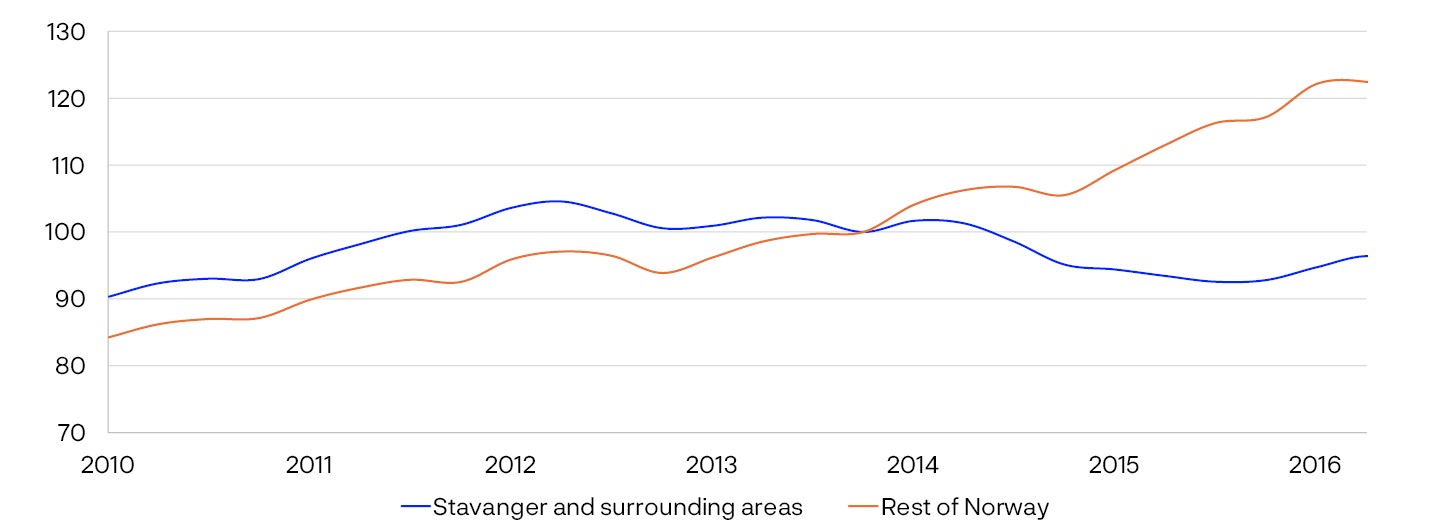

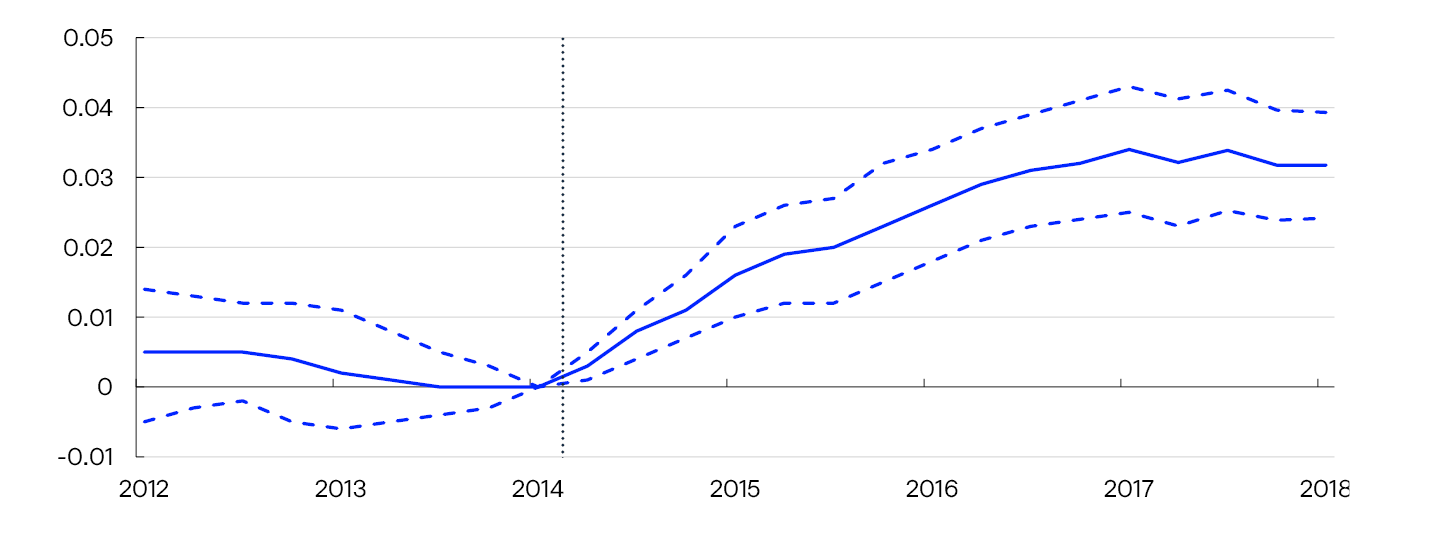

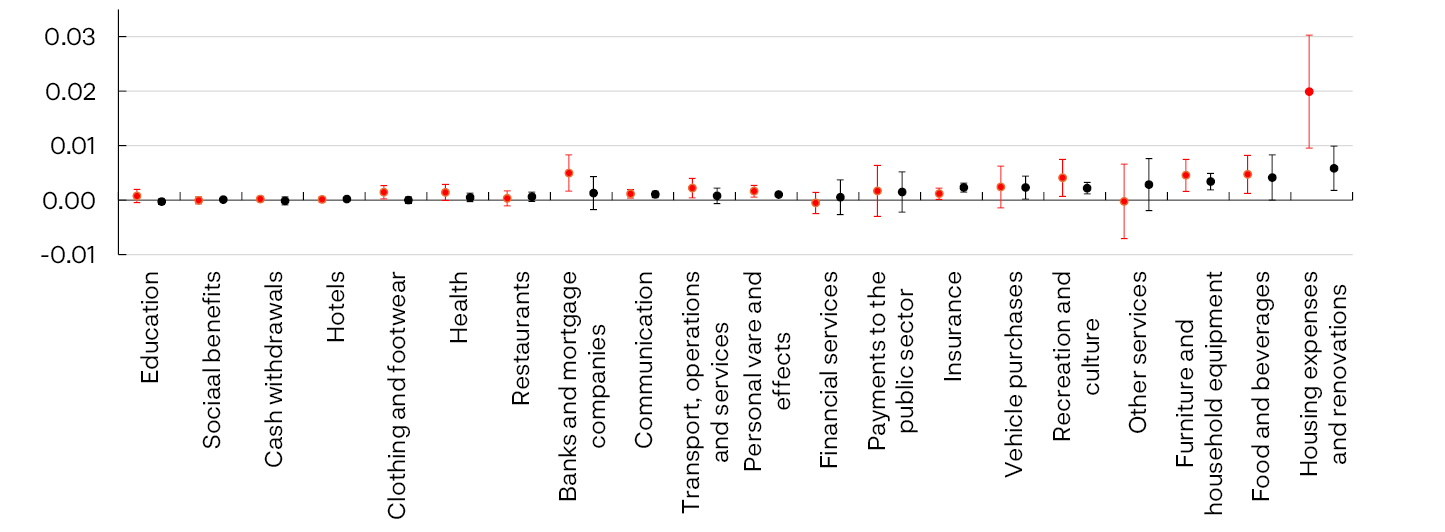

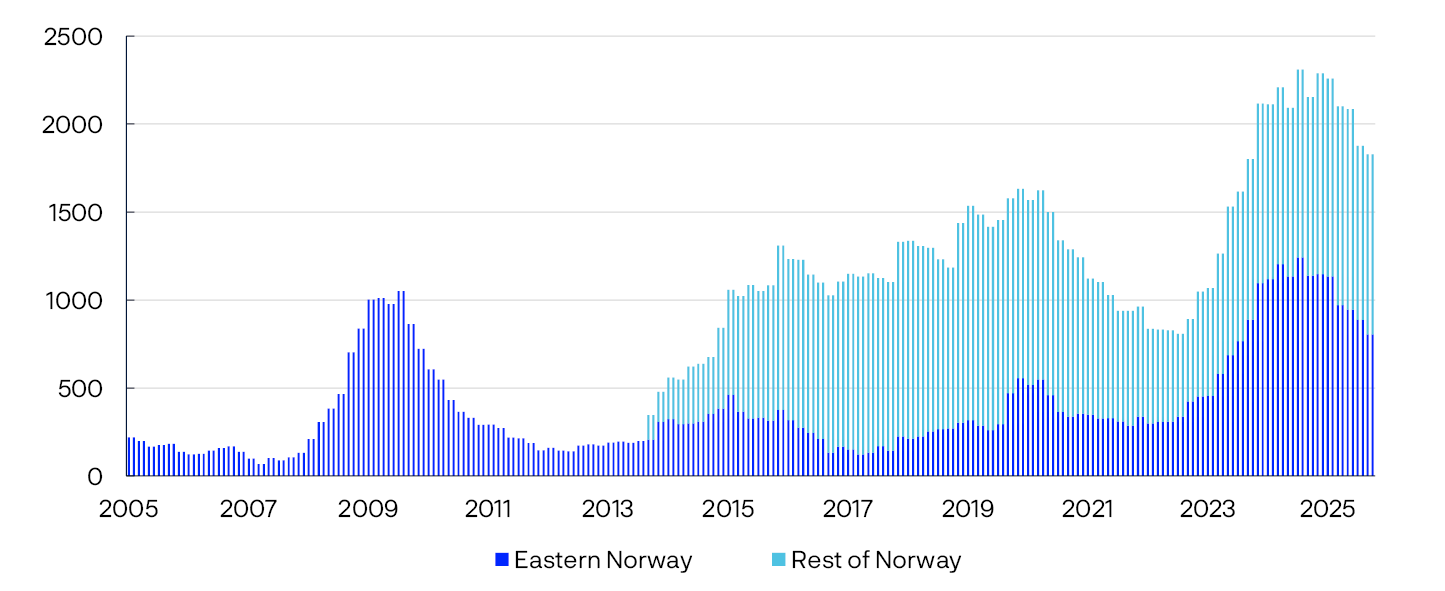

In connection with this Report, three analyses have been performed which shed light on developments in households’ access to the housing market and the behaviour of first-time buyers (see “Lower housing affordability in urban areas: how do first-time buyers respond?”). The first analysis indicates that housing affordability, defined here as the share of homes an individual can afford to buy with their own income within the debt-to-income requirements of the Lending Regulations, has declined over time, in particular in areas where housing demand is high. The other analysis finds that individuals with low income and/or low parental wealth postpone home purchases or remain longer in the rental market than before. The third analysis indicates that first-time buyers in the Oslo region, which is the area with the largest decline in housing affordability, to some extent postpone their purchase of a home until later in the life cycle and save more prior to purchase. They also receive more help to raise equity for home purchases than before, and the median size of the homes they purchase has changed little.