Inflation Expectations Across Economic Agents: Five Key Findings

Since 2002, Norges Bank has been monitoring inflation expectations across households, firms, social partners, and economists. This blog explores how these expectations evolve in response to macroeconomic conditions, their connection to wage expectations, and their reactions to energy price shocks. When inflation rises, there tends to be greater dispersion in beliefs about future inflation. Wage expectations, exhibit less-than-proportional responsiveness to increases in inflation expectations, thereby lowering the risk of wage-price spirals. Unexpected surges in electricity prices influence both short- and long-term inflation expectations.

Subjective expectations about inflation play a crucial role in macroeconomic models. The way households, firms, and institutions expect inflation to evolve plays a pivotal role in shaping their decisions. For households, inflation expectations affect their perceived real return on investments and consumption choices. Similarly, firms rely on inflation forecasts to determine pricing strategies, labor demand, and investment decisions. Professional forecasters and social partners like trade unions and employer organizations rely on their own expectations to guide financial strategies and wage negotiations.

Central banks pay close attention to both expert and public inflation expectations, as anchoring long-term inflation expectations safeguards price stability. In recent years, several central banks have made substantial investment in measuring inflation expectations through surveys. Norges Bank has been tracking inflation expectations through the Norges Bank Expectations Survey (NBES) since 2002.

The NBES: A Unified and Long-Term Perspective on Inflation and Wage Expectations in Norway

This harmonized survey captures inflation and wage expectations from households, business leaders, social partners, and economists for the short, medium and long term in Norway. What distinguishes the NBES from other inflation expectations surveys is its consistency and extensive time span. All participants answer very similar questions within the same timeframes, ensuring a shared macroeconomic environment. Importantly, no domestic macroeconomic data releases or interest rate decisions occur during the survey’s fieldwork, eliminating potential biases arising from timing or external shocks. This design avoids discrepancies caused by variations in question wording or survey timing, enabling comparisons across groups and over time. Additionally, the survey includes social partners—a vital yet often overlooked group—providing valuable insight into how wage-setting actors perceive inflation.

Revisiting Five Stylized Facts About Inflation Expectations

By leveraging this robust dataset, in recent research we revisit five key stylized facts about inflation expectations, highlighting how these beliefs differ among economic agents and evolve across economic environments.

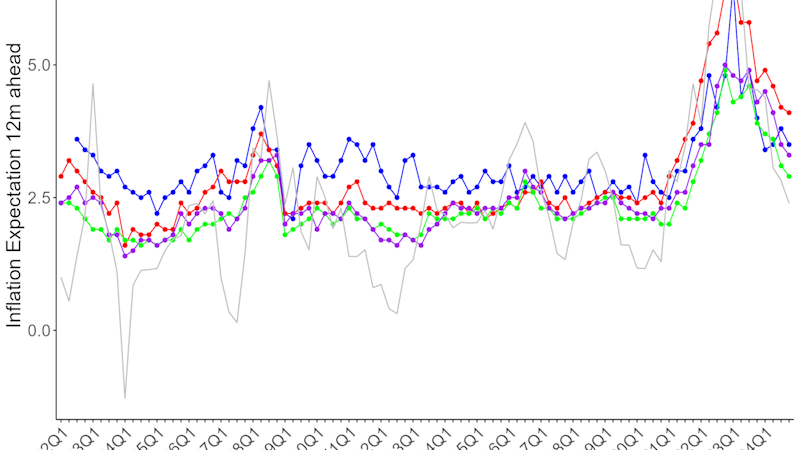

1. Level Differences in Expectations

The survey reveals differences in the inflation expectations of households, firms, and economists. Historically, household expectations have been higher than those of firms or professional forecasters. However, the post-2021 surge in inflation flipped this dynamic: firms' expectations surpassed households’, a shift attributed to energy price shocks that impacted households and firms differently. In contrast, social partners and economists maintained relatively stable and aligned expectations. Before the recent inflation surge, experts’ expectations were more accurate than non-experts, while over the last four years, households and firms have made smaller forecast errors than social partners and economists.

Figure 1. Average inflation expectations (12 months ahead) for different groups of agents as measured by the Norges Bank Expectations Survey. The grey line in (a) indicates year-over-year CPI inflation.

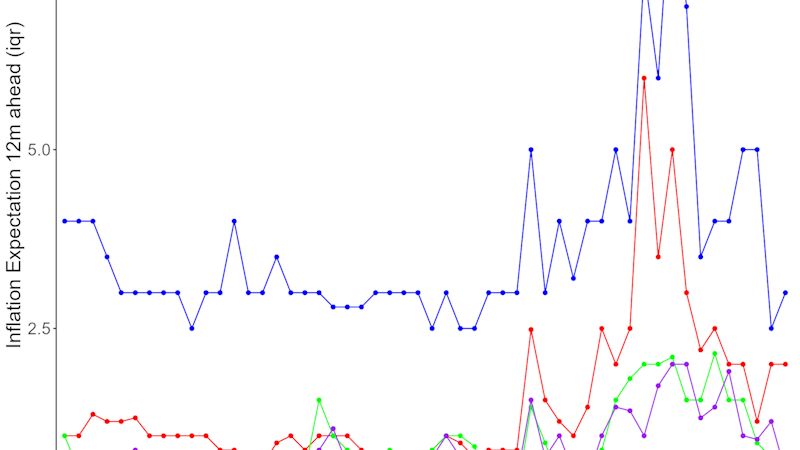

2. Cross-Sectional Disagreement

Under the assumption of Full-Information Rational Expectations (FIRE), all economic agents would form identical inflation expectations. However, the NBES data underscores the reality of significant dispersion among households, firms, and professionals. Households exhibited the most disagreement, linked to demographic factors like income and age, but disagreement among firms notably surpassed household levels after 2021. Much of this dispersion stemmed from differences in industry-specific expectations and correlates with observed own sales and purchase prices. This suggests that firms extrapolate from individual prices.

Figure 2. Interquartile range (75th percentile minus 25th percentile) of 12 month ahead inflation expectations for different groups of agents.

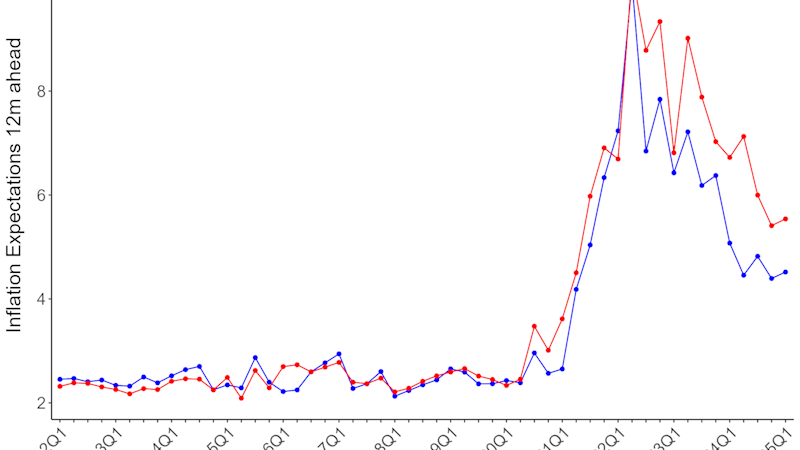

3. Term Structure of Expectations

When agents revise their short-term expectations, they typically also do so for long-term expectations, leading to a positive comovement. However, fluctuations in long-term expectations are smaller compared to short-term expectations, suggesting that the former are more anchored. An interesting finding emerges about the dynamics of the term structure—or the relationship between the level of expected inflation rates at different time horizons. Until 2021, households and firms anticipated higher inflation in the long run compared to short-term forecasts, creating an upward-sloping term structure. Post-2021, this structure inverted, with short-term expectations surpassing long-term ones as inflation was not expected to return to target in the immediate future.

4. Inflation-Wage Expectation Pass-Through

The interaction between inflation and wage expectations remains critical for understanding wage-price spirals, self-reinforcing cycles in which rising wages and increasing prices drive each other higher, contributing to persistent inflation in an economy. A high degree of pass-through from inflation expectations to wage expectations could then contribute to sustained inflation. Across all groups, we note that inflation expectations positively influence wage expectations, though the intensity of this relationship varies. Firms display the strongest pass-through from inflation expectations to wage bill forecasts, while households exhibit the weakest. Interestingly, the correlation slightly weakened for trade unions during the recent inflation surge but intensified for firms and economists. Despite this heterogeneity, for all groups the pass-through from wage expectations to inflation expectations is well below one, reducing the likelihood of wage-price spirals.

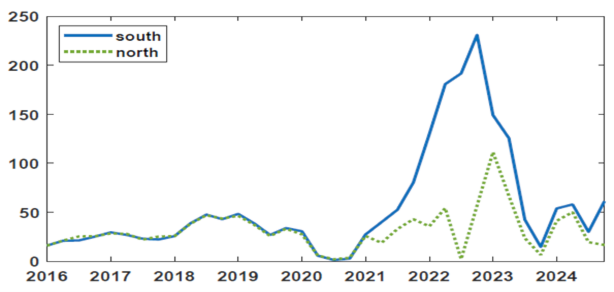

5. Response to Energy Price Shocks

Energy price shocks have long been associated with inflation expectation shifts. The NBES dataset provides a unique opportunity to study the impact of distinct electricity price shocks on different regions in Norway. In 2022, the Norwegian economy, like most European countries, experienced a massive increase in electricity prices. However, this shock was confined to the southern regions, due to both demand factors, such as high electricity demand and prices in Europe, and supply factors, i.e. restricted hydroelectric production caused by low water reservoires. Firms in affected regions increased their inflation expectations significantly, across multiple forecasting horizons and for a prolonged period of time. Instead, households did not exhibit similar changes, likely due to government subsidies that mitigated the impact on them. This finding underscore the importance of energy price shocks for inflation expectations.

Figure 3. Top panel: Electricity prices in Southern and Northern Norway, NOK/KWh. Bottom panel: Inflation Expectations (12 month ahead) of firms located in the North (blue line) and in the South (red line).

Main Takeways

The insights from the NBES challenge preconceived narratives about inflation expectation formation. One key takeaway from the study is the dynamic nature of inflation expectations. Stylized facts that were once observed under low-inflation environments underwent substantial shifts amid heightened inflation levels. These changes underscore the importance of revisiting theoretical models of expectations formation, to account for how the economic environment can shape the expectation-formation process. Overall, the harmonized and expansive NBES dataset pushes forward our understanding, paving the way for fine-tuned economic policies and more robust macroeconomic models.

0 Kommentarer