Estimating firms’ bank-switching costs

In this blog based on a new working paper, I ask: how costly is it for firms to switch banks? Where do these costs come from? And do banks exploit these costs by overcharging their locked-in borrowers?

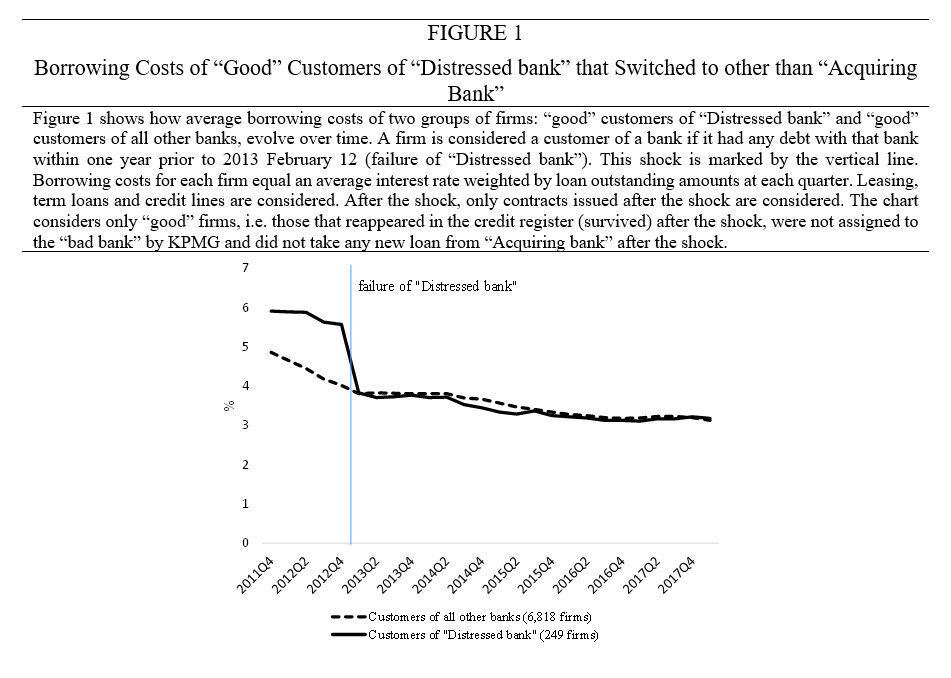

Firms avoid switching when it is costly, thus, it is difficult to observe switching costs in the data. In this blog, I look at forced switches, induced by bank closures, to provide a novel lower bound estimate of firms’ bank-switching costs. Lithuania offers an ideal setting for identification due to unexpected simultaneous closures of two banks, which I call “Distressed bank” and “Healthy bank”, and due to an exhaustive credit register, which reports interest rates and other characteristics of all outstanding loans in Lithuania. When a financially distressed bank was closed and its customers were forced to switch, their borrowing costs dropped immediately and converged to the rest of the market (see Figure 1). This suggests that the firms were locked-in and overcharged, and the fact that they paid the overcharge instead of switching suggests that switching costs were even larger than the overcharge. Hence, the overcharge, provides the lower bound estimate of switching costs.

What explains the drop in borrowing costs after the bank closure? Theory categorizes switching costs into informational and “shoe-leather” switching costs. Informational costs stem from interbank information asymmetries, whereby a firm’s inside bank (a bank with which a firm has a lending relationship) knows the firm better than outside banks. If the firm tries to switch, outside banks may suspect that the firm’s better-informed inside bank had refused to lend because the firm is bad or risky. Outside banks would, thus, offer high interest rates, which creates switching costs for firms. Inside banks can exploit this by overcharging their customers. If an inside bank closes, interbank information asymmetries disappear and outside banks can offer interest rates without stigmatizing switchers. This would cause a drop in firms’ borrowing costs.

Another explanation of the drop is that firms might always have been able to borrow at lower interest rates, but, due to “shoe-leather costs”, chose not to until they were forced. “Shoe-leather” switching costs may include transaction costs (e.g., search costs), artificial costs (e.g., loses of benefits provided by an inside bank, such as lower collateral requirements, larger loans, longer maturities, or expected support during crises), psychological costs (breaking the habit of borrowing from the same bank), and learning costs (installing and getting used to systems of a new bank). These costs are intangible and difficult to quantify but they allow inside banks to extract rents up to the point where firms are indifferent between switching and staying. An estimate of these rents would reveal the lower bound of total switching costs.

Informational switching costs are more relevant for better-quality and more opaque, i.e., younger and smaller, firms, while shoe-leather costs should affect all firms. I find that better-quality, younger and smaller firms were overcharged significantly more, which suggests that switching costs primarily stem from information asymmetries. I also find that “Healthy bank” did not overcharge its borrowers, which suggests that distressed banks might be less concerned about their reputation, and, therefore, are more likely to exploit switching costs.

I contribute to the literature by demonstrating that lending relationships with distressed banks can be harmful, and showing, for the first time, how hold-up costs disappear when a bank is shut down. In this way, I provide a novel identification of the hold-up problem and one of the first empirical estimates of firms’ switching costs in the loan market. I would expect to find comparable results in Norway and other similar loan markets, that are characterized by relatively small, opaque and bank-dependent firms and a high concentration of banks.

My results have policy implications. Firstly, although generally bank closures are costly, I provide one benefit for regulators to consider when resolving failed banks: A bank closure may improve credit allocation since better-quality firms, which are particularly important for productivity and employment, could borrow more cheaply. Secondly, regulators could monitor banks’ loan rates for early signs of banks’ distress. Thirdly, information asymmetries are an important source of switching costs, thus, regulators might be advised to aim to reduce these asymmetries further. For instance, a prevention of loan evergreening could improve the reliability of firms’ credit histories.

Bankplassen er en fagblogg av ansatte i Norges Bank. Synspunktene som uttrykkes her representerer forfatternes syn og kan ikke nødvendigvis tillegges Norges Bank. Har du spørsmål eller innspill, kontakt oss gjerne på bankplassen@norges-bank.no.

3 Kommentarer

Kommentarfeltet er stengt

Bjørn Solheim

And is PSD2 resulting in a standardization of integration interfaces that may reduce these lock-ins?

Karolis Liaudinskas

One of the main findings in the paper, however, is that switching costs stem primarily from information asymmetries as opposed to other types of switching costs, which suggests that IT-system integrations play a relatively limited role.

I believe PSD2 may have reduced these lock-ins to firms that rely heavily on online payments, but I would guess this was not a big issue for most of the Lithuanian firms in 2013, i.e., the time of the shock explored in the paper.

Bjørn Solheim

Karolis Liaudinskas